Scanner trial could improve brain tumour treatment

University of Aberdeen

University of AberdeenScientists at the University of Aberdeen and NHS Grampian have secured funding to generate never-before-seen brain tumour images with the aim of improving treatment.

Half of all glioblastoma patients die within 15 months of diagnosis even after surgery, radio and chemotherapy.

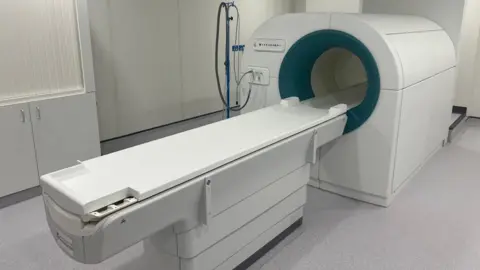

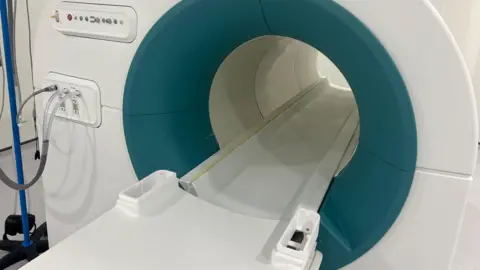

MRI scans used to monitor a tumour's behaviour can be imprecise but it is hoped the Field Cycling Imaging (FCI) scanner - developed in Aberdeen - will give clinicians better information.

The £350,000 in support - from the Scottish government - will fund a trial which will be carried out on a group of 18 patients.

MRI scanners were invented at the University of Aberdeen 50 years ago, but the new FCI scanner is the only one of its type used on patients anywhere in the world.

It can work at low and ultra-low magnetic fields which means it is capable of seeing how organs are affected by diseases in ways that were not previously possible.

It can vary the strength of the magnetic field during the patient's scan - acting like multiple scanners and extracting more information about the tissues.

The new technology can detect tumours without having to inject dye into the body, which can be associated with kidney damage and allergic reactions in some patients.

The team of doctors and scientists involved will scan glioblastoma patients undergoing chemotherapy after surgery and chemoradiotherapy.

University of Aberdeen

University of AberdeenIt is hoped the research will establish that, unlike conventional MRI scans, FCI can tell the difference between tumour growth and progression, and "pseudo-progression" which looks like a tumour but is not cancerous tissue.

Prof Anne Kiltie, chair in clinical oncology at the University of Aberdeen, who is leading the study, said: "We already have evidence that FCI is effective in detecting tumours in breast tissue and brain damage in stroke patients.

"Applying this exciting new technology to glioblastoma patients could give us a much more accurate and detailed picture of what is going on in their brain.

"If we can detect true tumour progression early, we can swap the patient to a potentially more beneficial type of chemotherapy.

"Providing certainty will also reduce anxiety for both patients and relatives and improve the quality of life of patients."

Prof Kiltie's role at the university is fully funded by the charity Friends of ANCHOR through its Dream Big appeal.

Chief executive Sarah-Jane Hogg welcomed the "really promising" development and thanked donors and fundraisers for their support.