Relief as Irish island's stolen bones return for good

RTÉ

RTÉ- Bones taken from the Irish island of Inishbofin 133 years ago have been returned

- Thirteen skulls and other fragments were given back by Trinity College Dublin

- The remains were reburied after a funeral Mass on the island on Sunday

- It brings to an end a long-running campaign by islanders to have the remains return to Inishbofin

Out of all the anniversaries, 133 isn't the most exciting.

It doesn't have the brand recognition of a 50, 75 or even 125; it has no name, no paper, crystal or gold.

But for the people of Inishbofin, an island off the west coast of Ireland, 133 years is now a golden date worth celebrating.

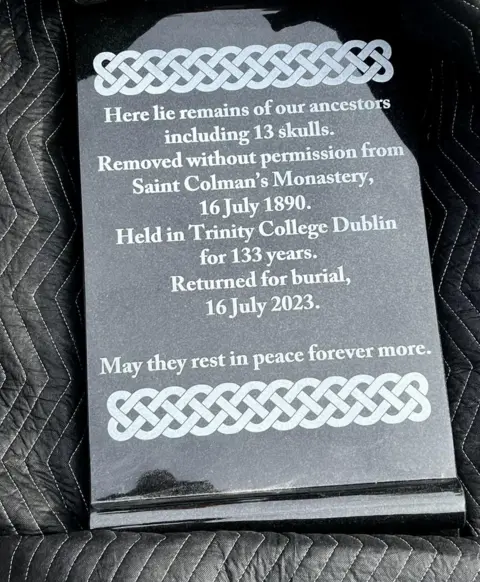

On Sunday, a funeral Mass took place on the island to mark the return of human remains stolen from a cemetery there 133 years ago.

Inishbofin Heritage Museum

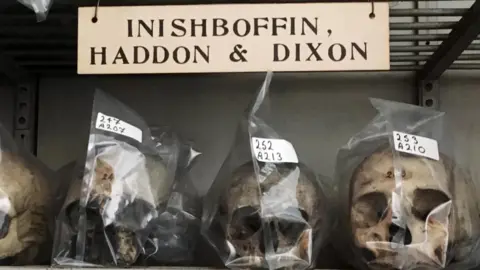

Inishbofin Heritage MuseumThe remains, including 13 skulls, were removed from Inishbofin in 1890 and subsequently kept at Trinity College Dublin (TCD).

In February, the university announced its intention to return the remains following a decade-long campaign by the islanders.

“I just feel so relieved and I’m so glad they’re back west," said Marie Coyne, who played an instrumental role in the saga of 'Bofin's bones.

She was speaking to BBC News NI before Sunday's service, a day after she escorted the remains from Trinity College to Athenry, County Galway.

"They played ball in the end, it has happened, so it's a relief," she added.

RTÉ

RTÉMarie runs a heritage museum on the island and she first became aware of the human remains more than 10 years ago when she came across an exhibition by Dr Ciarán Walsh.

What followed was a series of emails - the beginnings of a hard-fought campaign to return the bones to their intended place of rest.

A petition pleading for their return was signed by nearly every inhabitant on the island, which has a population of about 170.

"You have to respect the dead," said Marie.

"Museums all over the world are even giving back physical things like chalices or jewels or whatever, but this is not that kind of stuff - it’s human beings' bones.

"And there’s 13 of them and fragments of others."

But is there ever a case for the study, and ongoing storage, of human remains? Marie thinks not.

"It’s not an artefact; they’re trying to put different names on these things," she continued.

"If you think that’s your daughter, son, father, mother - and they were disrespected like that."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesInishbofin - simply known as ‘Bofin by the locals - is arguably less famous than the Arans, or the fictional isle of Inisherin which drew so much inspiration from the region, but it boasts the same charm that defines Irish islanders.

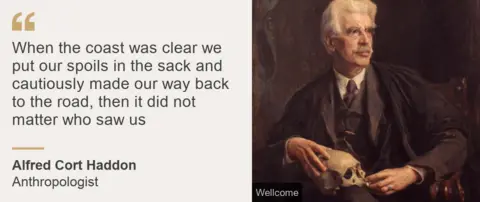

Its remoteness is perhaps what drew the likes of Alfred Cort Haddon, one of the two men who removed the remains in 1890, to take such a keen interest in its people.

At the time, researchers are thought to have speculated on the ethnicity of those living in far-flung Irish communities, seemingly sheltered from British influence.

"Oh we're mighty out here," Marie confirmed.

"Maybe they felt the people that were out on the fringes of society were more Irish, I don’t know."

Alfred Haddon may not be thought of too highly in ‘Bofin, but he was renowned for his opposition to racism and British colonisation.

But you don’t earn the nickname "head-hunter” for nothing.

On Wednesday 16 July 1890, Mr Haddon and Andrew Francis Dixon - who later became professor of anatomy at Trinity College - sailed to Inishbofin under the pretence of carrying out a fishing survey.

Trinity College Dublin

Trinity College DublinAt the time, there was interest in the study of craniometry, the measurement of the cranium, and anthropometry, the scientific measurement of individuals.

Like many others, Mr Haddon had developed a keen interest in the comparative study of human characteristics, which led to him removing a collection of human skulls from a recess in the wall of Teampall Chaomháin, adjacent to St Colman's Monastery on Inishbofin.

Journal entries from the time reveal how the pair of academics then smuggled the skulls off the island in a sack, claiming they were transporting the Irish moonshine poitín.

CURATOR.IE

CURATOR.IESince their removal, the remains were stored in Trinity College's old anatomy museum, but the university's governing board recently said they should be returned to Inishbofin.

More than 150 current residents on the island signed a petition calling for the return and condemning "the criminal nature of how these remains came into the possession of Trinity College in the first place".

"It’s been going on for the past 10 years, off and on, because of different things going on in Trinity," Marie explained.

"There were even some people who didn’t really want to give them back, and we were saying: ‘There’s documented evidence that they were stolen.'

"We just kept pushing for getting them back."

The Inishbofin remains were the first case to be examined by the university's Legacies Review Working Group, but it is also looking at Trinity's links with slavery and the British Empire.

Inishbofin Heritage Museum

Inishbofin Heritage MuseumThe return to Inishbofin is the first of its kind in Ireland and there is hope it will set a precedent for further repatriations.

Trinity College still holds more than 450 human remains sourced from countries including Nigeria, Thailand, South Africa and Australia.

But on Sunday the focus was on 'Bofin as islanders buried a coffin containing the remains.

Handmade by islander Christopher Day, whose ancestors also built coffins, it is a simple wooden casket in the traditional style.

“There’s no airs and graces or bling about it. These people would have never grown up with that; they were poor people and they grew up in hard times," said Marie.

"We’re just trying to make it very similar to what would have happened before."

Inishbofin Heritage Museum

Inishbofin Heritage MuseumFor Marie, the end of the campaign and the return of the bones was a relief - and meant she could turn her attention to Sunday's funeral service.

After travelling to Athenry, Marie and the funeral directors took the remains to Cleggan before setting sail for Inishbofin.

On Sunday, Mass was celebrated before they were buried in the grounds of St Colman's - back into the ground they were taken from 133 years earlier.

Inishbofin Heritage Museum

Inishbofin Heritage Museum