The mind-bending mirrors behind advanced technology

ESO/F Carrasco

ESO/F CarrascoHigh on a mountain, in Chile's bone dry Atacama desert the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is currently building the world's largest optical telescope.

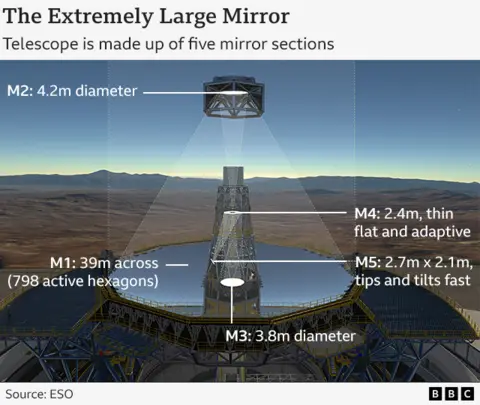

No time was wasted on choosing a name - it will be called the Extremely Large Telescope or ELT.

Instead, huge energy has gone into designing and building “the world’s biggest eye on the sky”, which should start collecting images in 2028 and is very likely to expand our understanding of the universe.

None of that would be possible without some of the most advanced mirrors ever made.

Florent Mallet/Mersen Boostec

Florent Mallet/Mersen BoostecDr Elise Vernet is an adaptive optics specialist at ESO and has been overseeing development of the five giant mirrors that will gather and channel light to the telescope’s measuring equipment.

Each of the ELT’s custom mirrors is a feat of optical design.

Dr Vernet describes the 14ft (4.25m) convex M2 mirror as “a piece of art”.

But perhaps the M1 and M4 mirrors best express the level of intricacy and precision required.

The primary mirror, M1, is the largest mirror ever made for an optical telescope.

“It’s 39m [128ft] in diameter, made up of [798] hexagonal mirror segments, aligned so that it behaves as a perfect monolithic mirror,” says Dr Vernet.

M1 will collect 100 million times more light than the human eye and must be able to maintain position and shape to a level of precision 10,000 times finer than a human hair.

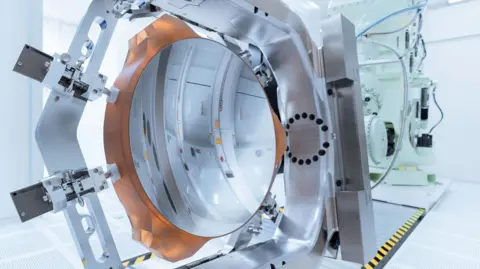

The M4 is the largest deformable mirror ever made and will be able to change shape 1,000 times per second to correct for atmospheric turbulence and the vibrations of the telescope itself that could otherwise distort imagery.

Its flexible surface is made up of six petals of a glass-ceramic material that is less than 2mm (0.075in) thick.

The petals were made by Schott in Mainz, Germany and then shipped to engineering firm Safran Reosc just outside Paris, where they were polished and assembled into the complete mirror.

All five mirrors are nearing completion and will soon be transported to Chile for installation.

While these enormous mirrors will be used to capture the light of the cosmos, ESO’s neighbours in Garching, at the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics, have created a quantum mirror to operate at the tiniest scales imaginable.

In 2020, a research team was able to make a single layer of 200 aligned atoms behave collectively to reflect light, effectively creating a mirror so small it cannot be seen by the naked eye.

In 2023, they succeeded in placing a single microscopically controlled atom at the centre of the array to create a “quantum switch” that can be used to control whether the atoms are transparent or reflective.

“What theorists predicted, and we observed this experimentally, is that in these ordered structures, once you absorb a photon and it gets re-emitted, it's actually emitted [in one predictable] direction and this is what makes it a mirror,” says Dr Pascal Weckesser, a postdoctoral researcher at the institute.

This ability to control the direction of atom-reflected light could have future applications in a number of quantum technologies like, for example, hack-proof quantum networks for storing and transmitting information.

Zeiss

ZeissFurther north-west in Oberkochen near Stuttgart, mirrors with another extreme property are being made by Zeiss.

The optics company spent years developing an ultra-flat mirror which has become a key component in the machines which print computer chips, called extreme ultraviolet lithography machines, or EUVs.

Dutch company ASML is the world's leading maker of EUVs, and Zeiss mirrors are an essential component of them.

Zeiss’s EUV mirrors can reflect light at very small wavelengths which enables image clarity at a tiny scale, so more and more transistors can be printed on the same area of silicon wafer.

To explain how flat the mirrors are, Dr Frank Rohmund, president of semiconductor manufacturing optics at Zeiss, uses a topographical analogy.

“If you took a household mirror and blew it up to the size of Germany, the highest elevation point would be 5m. On a space mirror [as in the James Webb Space Telescope], it would be 2cm [0.75in]. On an EUV mirror, it would be 0.1mm,” he explains.

This ultra-smooth mirror surface combined with systems that control the mirror’s positioning, also made by Zeiss, yield an accuracy level equivalent to bouncing light off an EUV mirror on the Earth’s surface and picking out a golf ball on the moon.

While those mirrors may already sound extreme, Zeiss has plans for improvement, to help make even more powerful computer chips.

“We have ideas about how to develop EUV further. By 2030, the goal is to have a microchip with one trillion transistors on it. Today, we are maybe at a hundred billion.”

That goal came closer with Zeiss's latest tech, which enables the printing of about three times more structures on the same area than the current generation of chip making machines.

“The semiconductor industry has this dominating strong roadmap which provides a drumbeat for all players contributing to the solution. With this, we are able to provide progress in terms of microchip fabrication which today allows things like artificial intelligence which were unthinkable even ten years ago,” says Dr Rohmund.

What humanity will understand and be capable of in ten years’ time remains to be seen, but mirrors will no doubt be at the heart of the technologies that take us there.