Splitting the atom: Why saying who was first is complex

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Donald Trump claimed US scientists split the atom in his inaugural speech, even he could not have imagined the chain reaction of online debate his boast would cause.

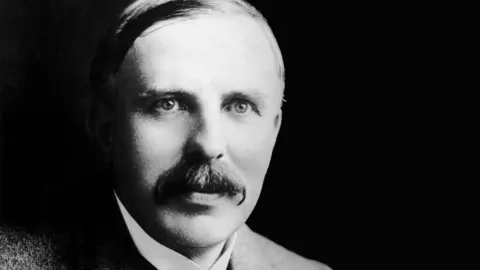

Many of those leaping on it suggested the honour was an Anglo-New Zealander one, as it was Sir Ernest Rutherford, a Kiwi scientific genius based at the then-Victoria University of Manchester, who made the scientific breakthrough in 1919.

In simple terms, that assertion is correct, but for those with an expertise in the field, the longer answer to who did it first is almost as complex as the science involved.

After all, as particle physicist Dr Harry Cliff put it, even the term "splitting the atom" is "problematic".

What is an atom?

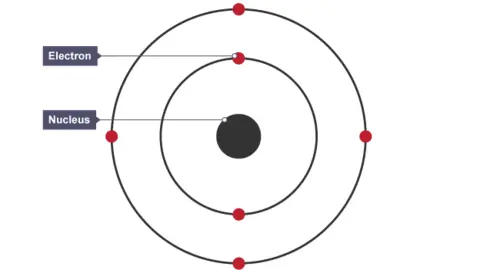

Atoms are the building blocks of all matter and are made up of a nucleus and a number of orbiting electrons.

Originally proposed in Ancient Greek philosophy, they were originally thought to bethe most minute particle in existence, with their name being derived from the Ancient Greek word for indivisible.

BBC Bitesize

BBC BitesizeIn 1803, John Dalton's atomic theory brought them into scientific view, but the Manchester scientist was clear that he agreed with the Ancient Greeks and believed they could not be broken into simpler, smaller particles.

Almost a century later, Joseph John Thomson, a fellow Mancunian working the University of Cambridge in 1897, discovered the electron, proving that the atom had smaller constituent parts.

That opened the door to subatomic hypotheses and experimentation.

What did Rutherford do?

Rutherford made a series of discoveries about the nature of atoms and, working with colleagues Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, presented a planetary model of the atom in 1911.

In it, he laid out how atoms have a central, positively charged nucleus with electrons orbiting like planets around a star.

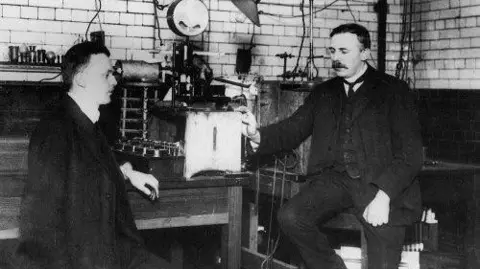

Later, he and his team conducted experiments in Manchester between 1914 and 1919, which have been described as being the first to "split the atom".

He blasted beams of radioactive particles into nitrogen gas, which changed into oxygen while "spitting out" a hydrogen nucleus.

University of Manchester

University of ManchesterDr Cliff said the scientists found "what we now call a proton", a building block particle present in all atoms.

He said what Rutherford was showing for the first time was "that you can perform these sorts of nuclear reactions, smacking one thing into another thing and then producing something new".

"That hadn't been done before," he added.

Rutherford himself did not use the term splitting, referring instead to "disintegration".

Writing in December 1917, he said he believed his experiments would "ultimately prove of great importance" and would "throw a good deal of light on the character and distribution of forces near the nucleus".

"I am also trying to break up the atom by this method," he added.

"In one case, the results look promising but a great deal of work will be required to make sure."

What happened next?

History lecturer Dr James Sumner said while Rutherford's work was clearly a "key conceptual breakthrough", it was less "splitting" and more "turning one element into another".

But Rutherford was far from finished with the atom.

He returned to his alma mater in 1919 as the director of the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory and oversaw the first deliberate attempts to "split" a nucleus.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Cliff said under his leadership in 1932, students John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton built one of the world's first particle accelerators, a powerful machine that "literally cleaved the atom in half".

He said in terms of a general understanding of a "Promethean human being smashing the atom to bits, that's when it happens".

However, Dr Sumner said it was "not the kind of splitting the atom that led to nuclear power and nuclear bombs.

That, he added, "comes a bit later still".

Why might US scientists have a claim?

Many people's understanding of atomic science is filtered through the lens of the top secret Manhattan Project, particularly since the Oscar-winning film about one of its most prominent figures, J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The US's research and development project was set up in 1942 with the aim of producing the first nuclear weapons which would harness atomic power.

Dr Sumner said while it was headquartered and funded in the US, the project was made up scientists from across the world who "collaborated across national boundaries".

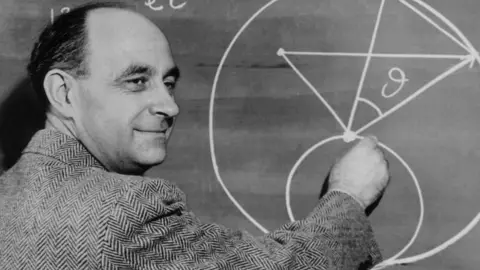

Among those recruited by Oppenheimer to join the team was Italian physicist Enrico Fermi.

It has been claimed he was first to split the atom during experiments in Rome in 1934, when he broke a nucleus into two or more smaller parts.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGerman chemists Otto Hahn, a former student of Rutherford's, and Fritz Strassmann, repeated his experiments over the next four years and by 1938, realised what Fermi had discovered was nuclear fission.

Fission sees the nucleus of unstable elements like uranium and plutonium split to release lots of energy.

Fermi fled Italy in 1939 and after arriving in Chicago, he built the first nuclear reactor, which induced and controlled a nuclear chain reaction, causing uranium atoms to continually split.

These, and the earlier efforts of Rutherford, laid the groundwork for the creation of atomic weapons, which harnessed the process of nuclear fission to devastating effect.

Dr Cliff said the Manhattan Project was "the sort of industrialization of that science to produce something that really has a huge impact on the world".

Where did it all lead?

Regardless of who was first to split the atom, the work of Rutherford, Walton, Cockcroft, Oppenheimer, Fermi, Geiger, Marsden and a host of other scientific pioneers paved the way for the nuclear age and the biggest science experiment in world history.

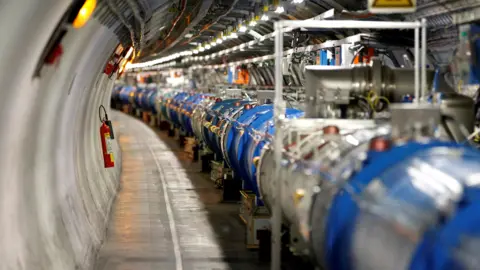

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a huge particle accelerator, was built underground beneath the Alps between 1998 and 2008 to smash atoms together and study the results.

It has led to discoveries such as the Higgs Boson - the so-called 'God particle' - and continues to allow scientists to investigate further and further into the subatomic world.

Reuters

ReutersDr Cliff, who is based at the LHC's home of Cern (European Organization for Nuclear Research), said the work there is focused on finding the "fundamental particles that make up the universe that we've not yet discovered", such as dark matter, an invisible substance which accounts for 80% of all matter and "everyone would love to find an explanation for".

He said those efforts "inherit directly" from Rutherford's early experiments, though were now "on a scale he could never have imagined".

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, X, and Instagram and watch BBC North West Tonight on BBC iPlayer.