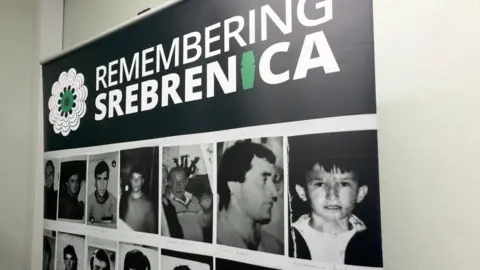

Srebrenica: Lives rebuilt but search for dead goes on

BBC

BBCErnesa Hajdarevic's father died in the Bosnian War aged just 24. As a girl she would regularly imagine him walking back into their lives.

She was just three at the time of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, when Bosnian Serb forces systematically murdered more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys, including her father Shaval, her grandfathers, uncles and cousins.

Now a mother-of-three, she has rebuilt her life in Birmingham, but still does not know the location of her father's remains.

Mrs Hajdarevic said her own children had now reached an age where they wanted to know about the past and the lives of their relatives, and she needed to find a way to explain.

The Srebrenica massacre, recognised by the UN as a genocide, was the climax of the war in Bosnia, a conflict that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.

The brutal killings became known as Europe's worst mass atrocity since World War Two.

Bosnian Serb forces laid siege to Srebrenica from 6 July 1995 and the killings of unarmed men started a week later.

The UN has declared 11 July as an annual day of remembrance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs events are held to mark the 30th anniversary, Mrs Hajdarevic said what caused her the most pain was waiting for her father's remains to be found.

She said the family had lived in hope that by this point – three decades on from the atrocity – they would know where to visit him.

As a child, she watched her mother receive calls as victims were identified and then make journeys to carry out tasks such as identifying her grandfather's T-shirt.

She said she was "always scared" when that happened, adding: "We had to survive many calls, especially for my grandfathers."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast year, the BBC reported how missing persons organisations in Bosnia and Herzegovina were still trying to trace about 7,000 people who had still not been found, with the remains of almost 2,000 lying unidentified in mortuaries.

Each day, Mrs Hajdarevic hopes for the call that will locate her father. She said: "Now I'm just waiting for that call and I'm hoping we will get it soon."

She counts herself as lucky to have been so young when the killings took place, because she does not remember everything.

But she said had she been older, she might have had more memories of her father, adding: "I'm also always thinking maybe if I was born a year earlier I would probably remember my father's face."

Living and working in Birmingham had brought positive developments she said, including that people are prepared to talk about what happened.

Mrs Hajdarevic said it was important for younger generations to understand events, especially now her own children were asking questions.

"I think that's why I need to get involved," she said. "I need to speak up. I need to start explaining, and I'm trying to explain the best way I can.

"I don't want to raise a child who hates others."

Lejla Golos, another survivor of the war, lost her grandfather and 17 family members in the conflict.

She left Sarajevo for the UK at the age of 15 and is now a mother-of-four offering counselling to people living with war-related trauma.

July, in particular, was always difficult, she said.

When she started to think about them, the people she had lost were "very much present", she said, but Ms Golos added: "Over the years, I've learned to get on with my life."

"Whether you have experienced the war for a week, like some of my friends who have been in concentration camp for a week, or whether you've been in a concentration camp for two months, the fact is that the trauma has left a scar on you either way, and you have to live with it."

Last month, England's first Bosnian consulate opened on Birmingham's Stratford Road.

After the war, the city served as the headquarters for the Bosnia and Herzegovina UK Network, supporting an estimated 10,000 refugees in Britain.

The consulate provides a diplomatic base and also runs community projects including jobs training and English language lessons.

Dr Anes Cerić, chief executive of the network and now honorary consul of Bosnia-Herzegovina for the Midlands, said such schemes also helped to bring people together so they could share experiences and talk.

"We've got families here that still are looking for loved ones and they still haven't found their bodies even after 30 years of the genocide, so you can imagine what they are facing," he said.

In a visit to Bosnia House, West Midlands mayor Richard Parker said refugees from Bosnia and other countries, including Syria and Ukraine, were being supported in the city.

Speaking about the importance of forging a sense of community, he said: "I want people from all over the world to feel welcome here, and be in a position where they feel safe here, and they can rebuild their lives."

Civic leaders and the Bosnian community are marking the anniversary with testimonies, speeches by faith leaders and music on Tuesday.

Follow BBC Birmingham on BBC Sounds, Facebook, X and Instagram.