BBC's twin-crises prompt apologies and promises - but will it work?

EPA

EPAOne report about failings in its programme-making is difficult for the BBC. Two on the same day could be catastrophic - and that's what BBC bosses woke up to on Monday morning.

The day has been about publicly apologising, announcing action plans and trying to turn a corner - on the Wallace misconduct story and on the failures over its Gaza documentary - after a deeply damaging few months.

But will it work?

On Wallace there are still questions about whether the BBC created a culture where presenters lived by different rules (something the recent culture review aims to get a grip on) and also whether there was enough active monitoring of what was going out on its platforms.

I think the BBC has a good case to say it did get a grip in the later years. Kate Phillips, now Chief Content Officer, warned Wallace about his behaviour in 2019 and after that, according to the report, no complaints were escalated to the BBC. If that is correct, the BBC can argue it thought the issue was sorted.

On the Gaza documentary about children in a warzone, with an investigation now launched by the regulator Ofcom into the BBC misleading audiences, it is by no means the end of the story.

But the review has on the face of it given the BBC a bit of breathing space. The culture secretary, who recently asked why nobody had been fired over the Gaza documentary, seems to have rowed back.

I understand that Director General Tim Davie and Chairman Samir Shah met with Lisa Nandy last week to reassure her. Her more conciliatory tone will have prompted a corporate sigh of relief after her recent pointed attacks directed at the BBC's leadership.

Questions still remain around whether anyone inside the BBC will lose their job. We know that the BBC team failed to get answers on the boy's family links, the investigation holds them partly responsible for the failures - and that the BBC says it is taking "fair, clear and appropriate action" to ensure accountability.

There is a question asked inside the BBC in situations where there have been failings. Will heads - or rather deputy heads - roll? It is a cynical take on whether there is real accountability at the top when something goes wrong. We still don't know the outcome here.

But more broadly, when it comes to Gaza, these past few months have been difficult.

When Davie gave evidence to MPs in March, a few weeks after he had pulled Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone from iPlayer, he told them he "lost trust in that film" once the fact that the child narrator was the son of a Hamas official became clear.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the ongoing war has led others to lose trust in the BBC and its coverage of what is happening in Gaza, where access by foreign journalists is prevented by Israel.

The corporation has been accused of antisemitism. Broadcasting a documentary without knowing that fact about the link to Hamas - and not informing the audience of it - opened it up to those accusations.

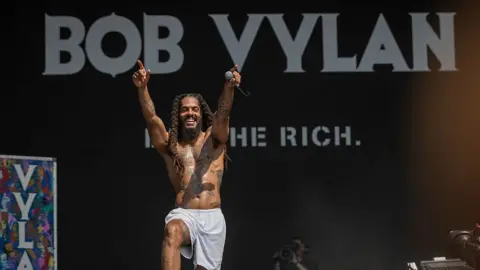

So did the BBC's failure properly to deal with the livestream from Glastonbury when the punk duo Bob Vylan chanted "Death to the IDF" and made other offensive comments.

There are people inside and outside the corporation who feel betrayed by the BBC's coverage. Some say it is biased against Israel and that the attacks on October 7th and the hostages have been forgotten. Some accuse the BBC of ignoring the plight of Gazans and Israel's actions in its coverage of the war.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt recently axed another documentary about the conflict, Gaza: Doctors Under Attack, because it said broadcasting it "risked creating a perception of partiality that would not meet the high standards that the public rightly expect of the BBC".

Less than two weeks ago, at a packed screening at London's Riverside Studios, hundreds watched it on the big screen, after it had been shown on Channel 4. I was there. The woman sitting next to me was in tears as the horrors unfolded on screen. She wasn't the only one.

The BBC has said it first delayed running the Gaza: Doctors Under Attack film in light of the investigation into the other documentary. It then dropped it, deciding it could not run after its presenter went on BBC Radio 4'sToday programme and called Israel 'a rogue state that's committing war crimes and ethnic cleansing and mass murdering Palestinians'.

The filmmakers at Basement Films have pushed back on that. On Monday they said "the film was never going to run on BBC News and we were given multiple and sometimes contradictory reasons for this, the only consistent theme for us being a paralysing atmosphere of fear around Gaza".

Whatever the true story about why it wasn't shown on the BBC, that claim - that the BBC's Gaza coverage is compromised by fear - is just as damaging. The BBC refutes it, but in some quarters, it appears to be taking hold.

In the screening room, Gary Lineker came onto the stage and said the BBC should "hang its head in shame" for not screening what he called "one of the most important films" of our time. He accused the BBC of bowing to pressure - and the audience noisily agreed.

Reporting the Israel-Gaza war has tested the BBC almost like never before. One insider said to me that neither side wants impartial reporting, what they want is partisan reporting. But, from all sides, the BBC has come under fire.

The BBC says it is "fully committed to reporting the Israel-Gaza conflict impartially, accurately and to the highest standards of journalism". It also says "We strongly reject the notion – levelled from different sides of this conflict – that we are pro or anti any position".

Two years ago the annual report was overshadowed by the Huw Edwards crisis, last year it was the Strictly allegations, this year it is not one but three stories.

The most important job for a director general is to secure charter renewal and the BBC has a strong story to tell and sell. But the difficulty for Tim Davie is that no matter how loud he bangs the drum for the BBC and its future, it is hard to be heard over the din of crisis.