The 'miracle' that enthralled a city 100 years ago

Liverpool Archdiocese

Liverpool ArchdioceseWhen the train carrying John Traynor pulled into Liverpool Lime Street Station one summer's day in 1923, his wife fought through the crowds to find several other women had already turned up claiming to be his spouse.

The clamour at his arrival was worthy of his fellow Liverpudlians The Beatles, who were not yet even born.

But Traynor was no music hall star or silent movie icon: he was a frail former sailor, paralysed, epileptic and doubly incontinent.

Or at least he had been before he had left his home city a few days before.

Born in 1883, John "Jack" Traynor had been a member of the Royal Navy Reserve and was mobilized at the outset of World War One. During the Battle of Antwerp he was hit in the head by shrapnel as he carried a wounded officer through a burning cornfield.

The wound left him with epilepsy, but nonetheless he went back to the active duty.

In 1915 he was at the disastrous Gallipoli invasion during which 130,000 British, Australian, New Zealander and French troops died trying to seize control of the Dardanelles from the Ottoman empire.

While Traynor managed to avoid falling victim to the onslaught for a week, his luck ran out on 8 May and he was hit by a hail of machine gun rounds.

He was wounded in the head and chest and the nerves of his right arm were severed, leaving him paralysed.

He returned to his home in the Dingle area of Liverpool a broken man, becoming so frail that his wife had to carry him up the stairs to bed.

It was a state he would remain in for several years, until, in 1923, he set out on a trip to the south of France from which he was to return a changed man.

Miraculously so, many would contend.

"I grew up with this story in my family about my great grandfather how he was significantly injured in WW1 but was cured after a Catholic pilgrimage so I wanted to get beyond family hearsay and family stories," said his great-great grandson Alex Taylor, a filmmaker who has researched his ancestor.

An unpublished memoir by Traynor's son John recalled how to eke out his disability pension, the sailor would sit on his front porch whittling down ballast wood he obtained from the ships that sailed out of Liverpool, and sell it as firewood.

"He was desperately ill, nothing had worked," said Taylor. "He heard about the first archdiocese pilgrimage to Lourdes and demanded that he went - against the better judgment of his family and parish priest."

The shrine of Lourdes has been a magnet for pilgrims since destitute teenager Bernadette Soubrious reported seeing visions of Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, in 1858.

A spring of water that bubbled up from the mud of the River Gave was said to have healing properties and Bernadette, who was later canonised by the church, said Mary had told people to bathe in the waters.

And Traynor was determined to do just that.

Liverpool Archdiocese

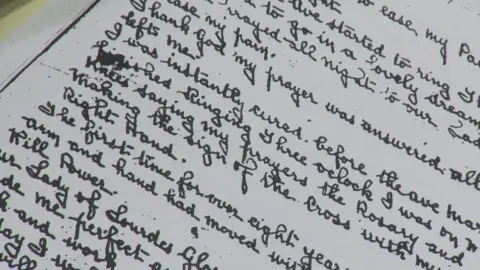

Liverpool ArchdioceseTraynor would recall in a letter that when he was bathed at Lourdes, his legs were "violently agitated".

He felt he had regained their use, but the people with him thought he was having a fit.

Later in the pilgrimage when the Archbishop of Rheims blessed him, his arm became "violently agitated".

Traynor was, he said, "instantly cured and able to make the sign of the cross".

Early the next morning he left his hospital bed and ran to the grotto, where Bernadette was said to have had her visions.

He spent 20 minutes on his knees making a thanksgiving prayer.

Three doctors examined him on 27 July and found he regained his ability to walk perfectly, as well as the full use and function of his right arm and legs.

The sores on his body healed completely and his fits ceased.

An opening in his skull created during surgery had also "diminished considerably".

By now, news of his miraculous recovery had reached Liverpool, and was spreading like wildfire.

Liverpool Archdiocese

Liverpool ArchdioceseTraynor returned to Liverpool pushing the wheelchair in which for many years he had had to sit.

He developed a successful coal haulage business delivering sacks of coal, and travelled every year to Lourdes as a stretcher bearer - or "brancardier" in French - to carry sick pilgrims.

In Liverpool, there was widespread belief that his apparent cure had been a miracle.

But the Ministry of Pensions was not convinced: refusing to believe he was healed, it continued to pay his disability pension until his death in 1940.

And it would be just over 100 years after his return from Lourdes that the Roman Catholic church would officially recognise what happened there as a miracle.

Last week, Traynor's recovery from epilepsy and paralysis caused by First World War wounds was declared the 71st "miracle" at the Roman Catholic Shrine of Lourdes.

Diocese of Salford

Diocese of SalfordOver the years there had been attempts to validate Traynor's cure, but these had come to nothing owing to the lack of enough "contemporaneous evidence".

But in 2023, Dr Kieran Moriarty, a retired consultant at the Royal Bolton hospital, was asked to review documents relating to Traynor during the Liverpool Catholic archdiocese's centenary pilgrimage to Lourdes.

It was commissioned by the current president of the Lourdes Office of Medical Observations (BdCM), Dr Alessandro de Franciscis.

Dr Moriarty unearthed a reference to a hidden report by Dr Vallet, acting President of the BdCM, published in December 1926.

The report revealed Dr Vallet had examined Traynor in July 1926 with the three doctors from Liverpool, and they had concluded that "the process of this prodigious healing is absolutely outside and above the forces of nature".

The report, which was published in French, appears never to have been sent to Liverpool.

'Long journey'

Dr Moriarty, 73, continued his research in the archdiocesan archives, which had boxes of files relating to Traynor, including his son's unpublished memoir .

"This has been a long journey for me," said Dr Moriarty.

"My grandparents were on Liverpool Lime Street station on 28 July 1923 when John Traynor returned from Lourdes cured.

"I heard the story of the cure when I was around eight years old and I always thought that it was a recognised miracle, until I came to Lourdes as a medical student in 1971 and realised it wasn't."

A commission convened by the Archbishop of Liverpool the Rt Rev Malcom McMahon met in Liverpool last month to validate Traynor's recovery

The archbishop declared said: "Given the weight of medical evidence, the testimony to the faith of John Traynor and his devotion to Our Blessed Lady, it is with great joy that I declare that the cure of John Traynor, from multiple serious medical conditions, is to be recognised as a miracle wrought by the power of God through the intercession of Our Lady of Lourdes.

For Taylor and other descendants of Traynor this official answer to their "prayers" has been a complete surprise.

"I'm still taking it in to be honest," he said. "We are delighted - the family were told a week before they attended Mass at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral last Sunday where the archbishop made the official announcement.

"The ramifications go far beyond our family."