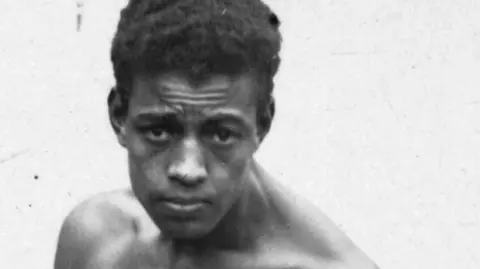

The barred boxer who could be first black statue

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCampaigners calling for a boxer to become the first black person to be honoured with a statue in Manchester have said the move would help young people in the city "feel themselves reflected".

Len Johnson, who competed from 1920 to 1933, was regarded as one of the best middleweight boxers of his generation, but was barred from elite competition because of his race.

His great-granddaughter Darianne Brown, who is part of the campaign calling for the statue, said it was "astounding to think" Manchester did not have any statues of black people.

She added that it would be "incredible if he could be the first".

The eldest of four siblings, Leonard Benker Johnson was born on 22 October 1902 in the Clayton area of the city.

His father William, a merchant seaman, came to Manchester from Sierra Leone, while his mother, Margaret Maher, was a Mancunian with Irish heritage.

Getty Images

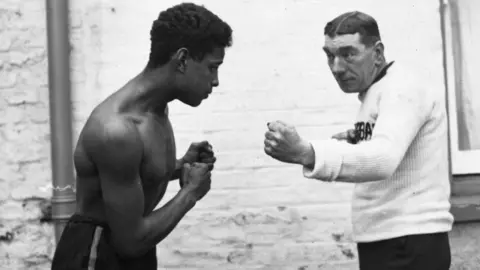

Getty ImagesA highly skilled boxer, with an educated left hand and a slippery defence that made him difficult to hit, his big break came in 1925, when he defeated Roland Todd, the reigning British Middleweight Champion, in two non-title bouts.

The wins should have automatically earned him the right to a title contest, but the British Boxing Board of Control forbade such a match, stating that it would breach Rule 24 of its code.

The rule, which was backed in 1911 by the then Home Secretary Winston Churchill and was operated by the board until 1948, stated title fight contestants "needed to have been born of white parents".

His considerable boxing talents saw him go on to record almost 100 victories, some against world champions, but the rule meant he was never given a shot at a championship belt.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn an interview with the Daily Dispatch which followed his retirement in 1930, he said he was "fed up with the whole business".

"I am barred from the Albert Hall, from the National Sporting Club and from all fights where this is big money," he said.

"The prejudice against colour has prevented me from getting a championship bout, although I consider I am well worthy of one."

He said if there was a public vote "on the question of whether I should be allowed to take part in a championship bout, there would be an overwhelming majority in my favour".

"I know in my heart that I shall never achieve those ambitions, so I am getting out of the game," he added.

Taslim Martin

Taslim MartinHe switched his fighting spirit from the ring to the streets and became a member of the Communist Party, a trade unionist and a local civil rights activist.

He ran unsuccessfully for a position on Manchester City Council six times and was recognised as a community leader in Moss Side, where he frequently intervened in cases involving racial discrimination.

Such was his standing that he was one of the local representatives at the influential Pan-African Congress held in Manchester in 1945.

Ms Brown said her great-grandfather, who died aged 71 in 1974, had not only been a popular and respected sportsman, but had also "really used that for good".

"He could have just stopped and said 'I’m not doing this any more, but he went further and created change'," she said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMancunian actor Lamin Touray, who is involved with the statue campaign, said everyone in the city needed to know who Len Johnson was.

"I had a photo of Muhammad Ali above my bed from eight years old, but we had our very own Muhammad Ali this whole time in Manchester," he said.

He said while Mr Johnson's story was "a piece of black British history", it was "also a shameful history about what the establishment did".

"Len wasn’t just a boxer," he said.

"He was a fighter outside of the ring politically, a massive fighter for civil rights.

"Young people in Manchester should feel themselves reflected in the history books and feel inspired."

A Manchester City Council representative said the authority supported the idea of a statue being erected in Len Johnson's honour, but a location was yet to be agreed.

Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham has also backed the campaign and said he felt the boxing great's story "absolutely needs to be told and celebrated".

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, X, and Instagram. You can also send story ideas to [email protected] and via Whatsapp to 0808 100 2230.