One death every seven minutes: The world's worst country to give birth

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the age of 24, Nafisa Salahu was in danger of becoming just another statistic in Nigeria, where a woman dies giving birth every seven minutes, on average.

Going into labour during a doctors' strike meant that, despite being in hospital, there was no expert help on hand once a complication emerged.

Her baby's head was stuck and she was just told to lie still during labour, which lasted three days.

Eventually a Caesarean was recommended and a doctor was located who was prepared to carry it out.

"I thanked God because I was almost dying. I had no strength left, I had nothing left," Ms Salahu tells the BBC from Kano state in the north of the country.

She survived, but tragically her baby died.

Eleven years on, she has gone back to hospital to give birth several times and takes a fatalistic attitude. "I knew [each time] I was between life and death but I was no longer afraid," she says.

Ms Salahu's experience is not unusual.

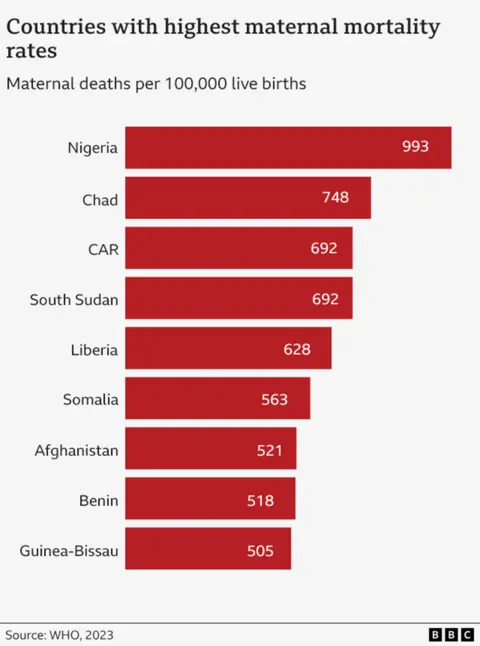

Nigeria is the world's most dangerous nation in which to give birth.

According to the most recent UN estimates for the country, compiled from 2023 figures, one in 100 women die in labour or in the following days.

That puts it at the top of a league table no country wants to head.

In 2023, Nigeria accounted for well over a quarter - 29% - of all maternal deaths worldwide.

That is an estimated total of 75,000 women dying in childbirth in a year, which works out at one death every seven minutes.

Warning: This article contains an image depicting a newly born child.

Henry Edeh

Henry EdehThe frustration for many is that a large number of the deaths – from things like bleeding after childbirth (known as postpartum haemorrhage) – are preventable.

Chinenye Nweze was 36 when she bled to death at a hospital in the south-eastern town of Onitsha five years ago.

"The doctors needed blood," her brother Henry Edeh remembers. "The blood they had wasn't enough and they were running around. Losing my sister and my friend is nothing I would wish on an enemy. The pain is unbearable."

Among the other common causes of maternal deaths are obstructed labour, high blood pressure and unsafe abortions.

Nigeria's "very high" maternal mortality rate is the result of a combination of a number of factors, according to Martin Dohlsten from the Nigeria office of the UN's children's organisation, Unicef.

Among them, he says, are poor health infrastructure, a shortage of medics, costly treatments that many cannot afford, cultural practices that can lead to some distrusting medical professionals and insecurity.

"No woman deserves to die while birthing a child," says Mabel Onwuemena, national co-ordinator of the Women of Purpose Development Foundation.

She explains that some women, especially in rural areas, believe "that visiting hospitals is a total waste of time" and choose "traditional remedies instead of seeking medical help, which can delay life-saving care".

For some, reaching a hospital or clinic is near-impossible because of a lack of transport, but Ms Onwuemena believes that even if they managed to, their problems would not be over.

"Many healthcare facilities lack the basic equipment, supplies and trained personnel, making it difficult to provide a quality service."

Nigeria's federal government currently spends only 5% of its budget on health – well short of the 15% target that the country committed to in a 2001 African Union treaty.

In 2021, there were 121,000 midwives for a population of 218 million and less than half of all births were overseen by a skilled health worker. It is estimated that the country needs 700,000 more nurses and midwives to meet the World Health Organization's recommended ratio.

There is also a severe lack of doctors.

The shortage of staff and facilities puts some off seeking professional help.

"I honestly don't trust hospitals much, there are too many stories of negligence, especially in public hospitals," Jamila Ishaq says.

"For example, when I was having my fourth child, there were complications during labour. The local birth attendant advised us to go to the hospital, but when we got there, no healthcare worker was available to help me. I had to go back home, and that's where I eventually gave birth," she explains.

The 28-year-old from Kano state is now expecting her fifth baby.

She adds that she would consider going to a private clinic but the cost is prohibitive.

Chinwendu Obiejesi, who is expecting her third child, is able to pay for private health care at a hospital and "wouldn't consider giving birth anywhere else".

She says that among her friends and family, maternal deaths are now rare, whereas she used to hear about them quite frequently.

She lives in a wealthy suburb of Abuja, where hospitals are easier to reach, roads are better, and emergency services work. More women in the city are also educated and know the importance of going to the hospital.

"I always attend antenatal care… It allows me to speak with doctors regularly, do important tests and scans, and keep track of both my health and the baby's," Ms Obiejesi tells the BBC.

"For instance, during my second pregnancy, they expected I might bleed heavily, so they prepared extra blood in case a transfusion was needed. Thankfully, I didn't need it, and everything went well."

However, a family friend of hers was not so lucky.

During her second labour, "the birth attendant couldn't deliver the baby and tried to force it out. The baby died. By the time she was rushed to the hospital, it was too late. She still had to undergo surgery to deliver the baby's body. It was heart-breaking."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Nana Sandah-Abubakar, director of community health services at the country's National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), acknowledges that the situation is dire, but says a new plan is being put in place to address some of the issues.

Last November, the Nigerian government launched the pilot phase of the Maternal Mortality Reduction Innovation Initiative (Mamii). Eventually this will target 172 local government areas across 33 states, which account for more than half of all childbirth-related deaths in the country.

"We identify each pregnant woman, know where she lives, and support her through pregnancy, childbirth and beyond," Dr Sandah-Abubakar says.

So far, 400,000 pregnant women in six states have been found in a house-to-house survey, "with details of whether they are attending ante-natal [classes] or not".

"The plan is to start to link them to services to ensure that they get the care [they need] and that they deliver safely."

Mamii will aim to work with local transport networks to try and get more women to clinics and also encourage people to sign up to low-cost public health insurance.

It is too early to say whether this has had any impact, but the authorities hope that the country can eventually follow the trend of the rest of the world.

Globally, maternal deaths have dropped by 40% since 2000, thanks to expanded access to healthcare. The numbers have also improved in Nigeria over the same period - but only by 13%.

Despite Mamii, and other programmes, being welcome initiatives, some experts believe more must be done – including greater investment.

"Their success depends on sustained funding, effective implementation and continuous monitoring to ensure that the intended outcomes are achieved," says Unicef's Mr Dohlsten.

In the meantime, the loss of each mother in Nigeria - 200 every day - will continue to be a tragedy for the families involved.

For Mr Edeh, the grief over the loss of his sister is still raw.

"She stepped up to become our anchor and backbone because we lost our parents when we were growing up," he says.

"In my lone time, when she crosses my mind. I cry bitterly."

More BBC stories from Nigeria:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBCGo to BBCAfrica.com for more news from the African continent.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, on Facebook at BBC Africa or on Instagram at bbcafrica