'Life-changing' gene therapy for children born blind

Moorfields Hospital

Moorfields HospitalAn experimental trial of gene therapy has helped four toddlers - born with one of the most severe forms of childhood blindness - gain "life-changing improvements" to their sight, according to doctors at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London.

The rare genetic condition means the babies' vision deteriorated very rapidly from birth.

Before the therapy, they were registered legally blind and only just able to distinguish between dark and light. After the infusion, all parents reported improvements - with some of their young children now able to begin to draw and write.

Further work is being done to confirm the early study, which appears in the Lancet medical journal.

Gene therapy for another form of genetic blindness has been available on the NHS since 2020.

The new work builds on that success by injecting healthy copies of a defective gene into the back of a child's eye, very early in life, to treat a severe form of the condition.

Moorfields Hospital

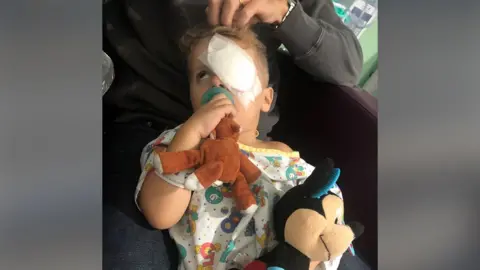

Moorfields HospitalJace, from Connecticut in the United States, had the gene therapy in London when he was just two years old.

As a young baby, his parents noticed something wasn't right about his eyesight.

"Around eight weeks old when babies should start looking at you and smiling, Jace wasn't doing that yet," says his mum DJ.

She knew instinctively there was an issue and began to search for the reason, which took 10 months.

After several visits to doctors and many tests, the family were told Jace had the ultra rare condition. It's caused by a mutation to a gene called AIPL1 and there is no established treatment.

"It was a shock," Jace's dad Brendan says of his first child.

"You never think it's going to happen to you, of course, but there was a lot of comfort and relief to finally find out... because it gave us a way to move forward."

The family was lucky to hear about an experimental trial being carried out in London - just by chance - when they were at a conference about the eye condition.

Jace's surgery was quick and "pretty easy", his mum says. He had four tiny scars in his eye where healthy copies of the gene were injected into the retina at the back of the eye through keyhole surgery.

These copies are contained inside a harmless virus, which goes through the retinal cells and replaces the defective gene. The healthy, working genes then kick start a process which helps the cells at the back of the eye work better and survive longer.

In the first month following treatment, Brendan noticed Jace squint for the first time on seeing bright sunshine streaming through the windows of their house.

His son's progress has been "pretty amazing", he says.

"Pre-surgery, we could have held up an object near his face and he wouldn't be able to track it at all.

"Now he's picking things off the floor, he's hauling out toys, doing things driven by his sight that he wouldn't have done before."

This may not be the last treatment he needs in his life, his parents say, but the improvements so far are helping him to know the world better.

"It's really hard to undersell the impact of having a little bit of vision," Brendan says.

No other options

Moorfields Hospital

Moorfields HospitalProf James Bainbridge, a retinal surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital, who helped lead the trial, said giving children the chance of sight improvement this early on could make a big difference to their development and ability to interact with people.

"Sight impairment in young children has a devastating effect on their development.

"Treatment in infancy with this new genetic medicine can transform the lives of those most severely affected," he said.

The four children, from the United States, Turkey and Tunisia, were all born with an aggressive form of Leber Congenital Amaurosis, where a genetic fault means the cells at the back of their eyes - that normally help distinguish light and colour- malfunction and rapidly die out.

Scientists at University College London developed the innovative procedure, which involves infusing healthy copies of the gene into the back of the eye, and Great Ormond Street Hospital specialists led on giving the procedure in the trial.

Unlike traditional scientific trials, families were offered this experimental therapy under a special licence designed for compassionate use, when there are no other options readily available.

Children had one eye treated each - a measure taken in case the treatment had any adverse effects.

They were aged between one and three when they had the procedure and their vision was then checked at intervals over the next four years, in a variety of ways - including moving down corridors and identifying doors.

Given their age, some children found the more formal eye tests challenging.

'Hugely impressive'

According to Moorfields' doctors, the results of the tests they completed, alongside the parent's reports of their improvements, give "compelling evidence" that all four benefited from the treatment and were seeing more than would be expected with the normal course of the disease.

Vision in their untreated eyes, meanwhile, deteriorated, as expected.

Consultant eye surgeon, Prof Michel Michaelides, at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, added: "The outcomes for these children are hugely impressive and show the power of gene therapy to change lives."

The team plans to monitor the children to see how long-lasting the results are.

The results so far give them hope that intervening early in other childhood genetic eye conditions could offer the "greatest benefit" and ultimately transform children's lives.

Sign up here to receive our new weekly newsletter highlighting uplifting stories and remarkable people from around the world.