We always joked dad looked nothing like his parents - then we found out why

Family photo

Family photoMatthew's dad had brown eyes and black hair. His grandparents had piercing blue eyes.

There was a running joke in his family that "dad looked nothing like his parents", the teacher from southern England says.

It turned out there was a very good reason for this.

Matthew's father had been swapped at birth in hospital nearly 80 years ago. He died late last year before learning the truth of his family history.

Matthew - not his real name - contacted the BBC after we reported on the case of Susan, who received compensation from an NHS trust after a home DNA test revealed she had been accidentally switched for another baby in the 1950s.

BBC News is now aware of five cases of babies swapped by mistake in maternity wards from the late 1940s to the 1960s.

Lawyers say they expect more people to come forward driven by the increase in cheap genetic testing.

'The old joke might be true after all'

During the pandemic, Matthew started looking for answers to niggling questions about his family history. He sent off a saliva sample in the post to be analysed.

The genealogy company entered his record into its vast online database, allowing him to view other users whose DNA closely matched his own.

"Half of the names I'd just never heard of," he says. "I thought, 'That's weird', and called my wife to tell her the old family joke might be true after all."

Matthew then asked his dad to submit his own DNA sample, which confirmed he was even more closely related to the same group of mysterious family members.

Matthew started exchanging messages with two women who the site suggested were his father's cousins. All were confused about how they could possibly be related.

Working together, they eventually tracked down birth records from 1946, months after the end of World War Two.

The documents showed that one day after his father was apparently born, another baby boy had been registered at the same hospital in east London.

That boy had the same relatively unusual surname that appeared on the mystery branch of the family tree, a link later confirmed by birth certificates obtained by Matthew.

It was a lightbulb moment.

"I realised straight away what must have happened," he says. "The only explanation that made sense was that both babies got muddled up in hospital."

Matthew and the two women managed to construct a brand new family tree based on all of his DNA matches.

"I love a puzzle and I love understanding the past," he says. "I'm quite obsessive anyway, so I got into trying to reverse engineer what had happened."

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAn era before wristbands

Before World War Two, most babies in the UK were born at home, or in nursing homes, attended by midwives and the family doctor.

That started to change as the country prepared for the launch of the NHS in 1948, and very gradually, more babies were delivered in hospital, where newborns were typically removed for periods to be cared for in nurseries.

"The baby would be taken away between feeds so that the mother could rest, and the baby could be watched by either a nursery nurse or midwife," says Terri Coates, a retired lecturer in midwifery, and former clinical adviser on BBC series Call The Midwife.

"It may sound paternalistic, but midwives believed they were looking after mums and babies incredibly well."

It was common for new mothers to be kept in hospital for between five and seven days, far longer than today.

To identify newborns in the nursery, a card would be tied to the end of the cot with the baby's name, mother's name, the date and time of birth, and the baby's weight.

"Where cots rather than babies were labelled, accidents could easily happen", says Ms Coates, who trained as a nurse herself in the 1970s and a midwife in 1981.

"If there were two or more members of staff in the nursery feeding babies, for example, a baby could easily be put down in the wrong cot."

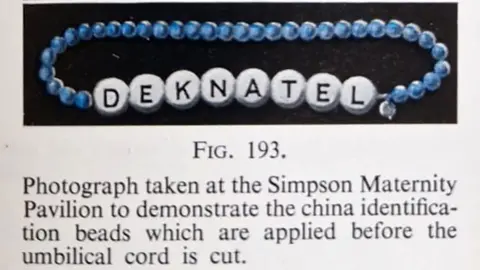

By 1956, hospital births were becoming more common, and midwifery textbooks were recommending that a "wrist name-tape" or "string of lettered china beads" should be attached directly to the newborn.

A decade later, by the mid-1960s, it was rare for babies to be removed from the delivery room without being individually labelled.

Textbook for Midwives, 1956

Textbook for Midwives, 1956Stories of babies being accidentally switched in hospital were very rare at the time, though more are now coming to light thanks to the boom in genetic testing and ancestry websites.

The day after Jan Daly was born at a hospital in north London in 1951, her mother immediately complained that the baby she had been given was not hers.

"She was really stressed and crying, but the nurses assured her she was wrong and the doctor was called in to try to calm her," Jan says.

The staff only backed down when her mum told them she'd had a fast, unassisted delivery, and pointed out the clear forceps marks on the baby's head

"I feel for the other mother who had been happily feeding me for two days and then had to give up one baby for another," she says.

"There was never any apology, it was just 'one of those silly errors', but the trauma affected my mother for a long time."

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesNever finding out

Matthew's father, an insurance agent from the Home Counties, was a keen amateur cyclist who spent his life following the local racing scene.

He lived alone in retirement and over the last decade his health had been deteriorating.

Matthew thought long and hard about telling him the truth about his family history but, in the end, decided against it.

"I just felt my dad doesn't need this," he says. "He had lived 78 years in a type of ignorance, so it didn't feel right to share it with him."

Matthew's father died last year without ever knowing he'd been celebrating his birthday a day early for the past eight decades.

Since then, Matthew has driven to the West Country to meet his dad's genetic first cousin and her daughter for coffee.

They all got on well, he says, sharing old photos and "filling in missing bits of family history".

But Matthew has decided not to contact the man his father must have been swapped with as a baby, or his children – in part because they have not taken DNA tests themselves.

"If you do a test by sending your saliva off, then there's an implicit understanding that you might find something that's a bit of a surprise," Matthew says.

"Whereas with people who haven't, I'm still not sure if it's the right thing to reach out to them - I just don't think it's right to drop that bombshell."