A view from the press bench in fraud nurse trial

Gareth Everett/Huw Evans Picture Agency

Gareth Everett/Huw Evans Picture AgencyAny journalist who reports crown court trials will tell you to expect the unexpected.

But nothing could have prepared me for the story of Tanya Nasir, the woman who became known to me and my colleagues as the fake nurse.

That was unfair. She was a nurse. She had an adult nursing qualification.

But that was pretty much the only truth in Tanya Nasir's life.

The rest was a work of fiction, a series of incredible lies which were slowly and meticulously picked apart during the course of her trial at Cardiff Crown Court.

And from my seat on the press bench, I had the perfect vantage point.

Press benches are usually small seats, mostly wooden and the cause of aches and pains if journalists sit on them for any length of time.

But what they lack in comfort, they more than make up for in a privileged view of trials.

We can see everyone and everything that goes on in court and everyone can see us.

And in the trial of Tanya Nasir, that was a problem, a very serious problem which could have landed me in the cells.

But before I get to that, I will explain why I was sitting on the press bench.

Tanya Nasir was tried and convicted of nine counts of fraud and fraud by false representation, and she has now been jailed for five years.

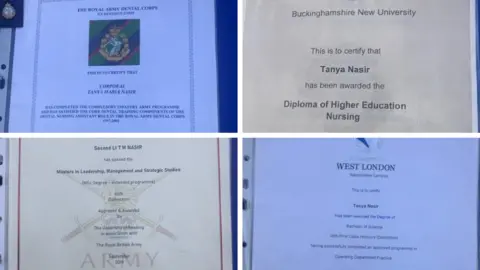

She claimed to be a highly qualified nurse with extensive experience in areas including adult and child intensive care.

She said she had dentistry and operating theatre qualifications as well as degrees in physics, astrophysics and a masters qualification in leadership.

She also claimed to be a reservist in what she said was the "Royal British Army".

Nasir claimed to have served in a field hospital "500 metres from the front line in Afghanistan", as well as in Iraq and Kosovo.

She told an interview panel she would need time off to train with her regiment on the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia, home to British and US military bases.

Then there was her work with charities including the Red Cross and Oxfam, bringing aid to people in conflict zones around the world.

It was all absolute rubbish.

By faking references and lying about her qualifications and her Army career, she secured nursing posts in London and Bedfordshire.

Then, in 2019, she was appointed to a senior role at the Princess of Wales Hospital in Bridgend.

She became the neonatal ward manager. It was a hugely responsible and important post, leading a department of nurses and doctors caring for the smallest and sickest babies.

Five months after she began work there, she was found out by a sharp-eyed matron who noticed something was not quite right about the code on her Nursing and Midwifery Council registration.

It read 13 - to denote that she had qualified as a nurse in the financial year 2013/14. But during the interview for the job and on her application form, she said she had qualified in 2010.

That is when the lies unravelled and, in July this year, she went on trial.

But back to my problem on the press bench. When Ms Nasir stepped into the witness box, her lies were so big, so ridiculous and at times infuriating, that it was very difficult not to look shocked.

I was shocked. I couldn't believe what she was saying - and with such confidence.

I have reported from Afghanistan and knew what she was saying about her deployments there simply was not true. It was fantasy.

I thought of the people I had met who were working in the real field hospitals, treating injured service personnel and local Afghans injured by IEUs, including children. It was difficult, dangerous and heartbreaking work.

They were people of real quality, clinical professionals with the quiet confidence of people who have seen so much.

She was not one of them. Nowhere near.

She talked about humanitarian work in Kenya, Kosovo and Syria and her expertise in neonatal intensive care techniques.

I could hear nurses from her former hospitals in the public gallery, sighing as she tied herself in medical knots.

And then there was her military service number. This was the big one.

At one point, prosecuting barrister Emma Harris asked Nasir for her military service number, an eight digit number which is assigned to all military personnel.

But Nasir couldn't remember it.

As I wrote a shorthand note of her reply, I could feel my eyes widening.

What she had said, or rather not said, was incredible.

No one who has served ever forgets that number. I've interviewed D Day veterans who reeled it off without missing a beat, more than 60 years after landing on the Normandy beaches with German fire ringing in their ears.

But the lieutenant, captain, doctor - yes, she used all those titles - could not remember her number. She could not remember it because she did not serve.

Looking shocked at something a defendant says in court is not allowed.

The 12 people on a jury decide a defendant's innocence or guilt based on the evidence they hear in court. Anyone who tries to influence their thinking will find themselves in serious trouble with the judge, facing a fine or even a prison sentence.

I looked down at my notepad, continued taking my notes, and the moment passed. I was shocked that I was so shocked.

Inside I was screaming: "You're not telling the truth, none of this is true, this is crazy."

After the verdict, I tried to speak to Tanya Nasir as she left the court, to ask her why she lied so much and to so many people.

She hid under an umbrella in the bright sunshine, laughing as she walked away.