'Care order that restricted freedom as child left me traumatised'

BBC

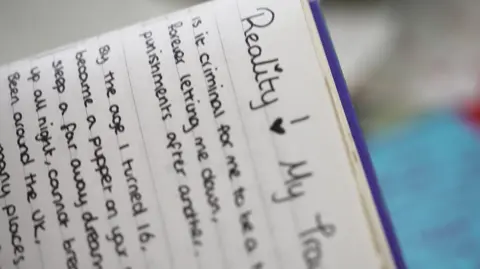

BBCA woman who experienced "constant disruption and instability" after being made the subject of a court order while in care has said she wants to "ensure other children don't go through what I have been through".

Chereece, 23, said living with a Deprivation of Liberty (DoL) order caused "more trauma and more damage" and saw her moved to seven children's homes, a secure adult hospital and an activity centre as a child.

The increasing use of the orders in England and Wales, which stop young people from leaving places they are put in by local authorities, has put further pressure on available accommodation.

Ofsted and charities have warned that as a result, at-risk children were losing their freedom.

In 2017/18, there were 103 DoL applications in England, while in 2023/24, there were 1,238.

The latest data showed that 21% of DoLs in England and Wales lasted more than 12 months and 57% of those subject to an order were aged between 13 and 15.

The orders are the most extreme intervention the state can make to keep children and others safe.

They mean a child must live somewhere they are not free to leave or are put under continuous supervision.

But some of the children are severely traumatised by abuse and neglect, and have complex needs requiring high levels of skilled care and supervision, meaning that suitable accommodation settings can be limited.

The rise comes amid a shortage of registered children's accommodation and warnings about placing young people in non-registered homes, of which there are 117 in the north-west of England.

Councils said the use of "unregistered" homes due to a lack of suitable options was not a choice they wanted to make.

- If you are affected by any of the issues in this story, you can visit the BBC Action Line for information on available support and advice

Chereece, from Stockport in Greater Manchester, started running away after she was put in a children's home 35 miles from her hometown.

She said she was "running away to be with [her] friends and family" and that when she was deprived of her freedom, it caused "more trauma and more damage".

She had been moved seven times to different homes in Newton-le-Willows, St Helens, Manchester, Runcorn and Warrington.

She was also housed in non-children's homes, including a secure adult hospital and in an activity centre in Wales where she had to move to a different cabin every few days.

Chereece said she experienced "constant disruption and instability" and made a threat to take her own life because she "didn't want to keep going through what the system was putting [her] through".

Under a DoL she was then put in a secure adult facility in Shrewsbury where she had to "sleep with the door open with a nurse watching" before being moved to a secure children's hospital in Manchester, and then a unit in Peterborough.

"Things like clothes, TV, mobile phone or any beauty products had to be earned," she said.

At 16, she fought to have the DoL overturned with the help of a social worker.

She said the judge at the tribunal said she should never have been put in a secure unit and understood that her running away was because she was not being listened to and not having her needs met.

'National scandal'

A report by the Children's Commissioner last December found many children who were subject to a DoL end up living in temporary accommodation like "holiday camps, activity centres or caravans" because of the lack of suitable places in registered children's homes, describing it as "a national scandal".

Ofsted told the BBC it is not unusual for local authorities to try up to 200 places and be turned away.

The shortage has meant children have been placed in unregistered homes , supervised by agency staff and often without access to education or vital psychological therapies.

Ofsted has previously said that any home that was not registered and therefore not inspected and rated by Ofsted was "illegal".

Jacob Sacks-Jones

Jacob Sacks-JonesKatharine Sacks-Jones, chief executive of Become, a charity for children in care, said DoLs were being used more than they should have been, and the rise of unregistered children's homes was a "symptom of the crisis facing children's social care".

She added: "Local authorities are saying the only way they can keep a child safe now, and the only way they can get them somewhere to live, is with a Deprivation of Liberty Order.

"I think that's really concerning because they should be a very, very last resort."

Lisa Harker, head of the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, said DoLs were "always designed to be a last resort option and a temporary measure."

"The data shows numbers of applications rising across the country, to well over a thousand young people a year, and tragically the majority of them are still in this situation six months later," she added.

Ofsted warned that 12% of children placed in the unregistered settings that they investigated last year were subject to a DoL.

The watchdog said: "These are some of the most vulnerable children in care.

"They should not be placed in settings with no regulatory or independent oversight."

Yvette Stanley, Ofsted's director for social care, said: "Local authorities will tell us that before they've considered an unregistered children's home, they might have tried 200 places and been turned away.

"I'm really worried that the most vulnerable children, their needs are escalating, not diminishing, because they're not getting that help.

"I worry about children in the wrong places with the wrong staff, the wrong oversight, adding to the harm they've already experienced."

Last November homes not registered by Ofsted became illegal for children in care or care leavers up to the age of 18.

The measure was introduced after the number of unregistered private children's homes rose by 500% in the last three years.

The Department for Education said: "It is entirely unacceptable that due to a shortage of placements that cater to complex needs, vulnerable children are being housed in inappropriate, unregistered accommodation.

"We're committed to increasing provision for all children in care, including those with more complex needs, and through our landmark Children's Wellbeing and Schools bill we're giving Ofsted stronger powers to crack down on providers found to be running illegal, unregistered homes."

Arooj Shah, the chairperson of the Local Government Association's Children and Young People Board, said: "No council wants to place a child in an unregistered setting, and it is extremely concerning that in many cases, a lack of choice means provision is not fully meeting children's needs."

She described the cost of care placements as "astronomical" and said central and local government, the NHS and Ofsted needed to work together to fix the situation.

She added: "It is helpful that the Government is taking action to tackle the broken 'market' for children's social care placements, including through the Children's Wellbeing and Families Bill, and we will continue to work with them to make sure every child has the loving, supportive home that they need and deserve."

Chereece said she was now living happily with her daughter, back in her hometown of Stockport, and working for the civil service.

She said she wanted to share her experience to "ensure other children in care don't go through what [she has] been through".

"I hope my daughter never has to experience anything like that and she'll grow up in a loving home and she'll know that she's got someone who is supporting her and by her side all the way through her life experiences," she added.

- With additional reporting by Jonathan Fagg, BBC England Data Unit

Read more stories from Cheshire, Lancashire, Greater Manchester and Merseyside on the BBC, watch BBC North West Tonight on BBC iPlayer and follow BBC North West on X.