Russia's intensifying drone war is spreading fear and eroding Ukrainian morale

Everyone agrees: it's getting worse.

The people of Kyiv have, like the citizens of other Ukrainian cities, been through a lot.

After three and a half years of fluctuating fortunes, they are tough and extremely resilient.

But in recent months, they have been experiencing something new: vast, coordinated waves of attacks from the air, involving hundreds of drones and missiles, often concentrated on a single city.

Last night, it was Kyiv. And the week before too. In between, it was Lutsk in the far west.

Three years ago, Iranian-supplied Shahed drones were a relative novelty. I remember hearing my first, buzzing a lazy arc across the night sky above the southern city of Zaporizhzhia in October 2022.

But now everyone is familiar with the sound, and its most fearsome recent iteration: a dive-bombing wail some have compared to the German World War Two Stuka aircraft.

The sound of swarms of approaching drones have sent hardened civilians back to bomb shelters, the metro and underground car parks for the first time since the early days of the war.

"The house shook like it was made of paper," Katya, a Kyiv resident, told me after last night's heavy bombardment.

"We spent the entire night sitting in the bathroom."

"I went to the parking for the first time," another resident, Svitlana, told me.

"The building shook and I could see fires across the river."

The attacks don't always claim lives, but they are spreading fear and eroding morale.

After an attack on a residential block in Kyiv last week, a shocked grandmother, Mariia, told me that her 11-year old grandson had turned to her, in the shelter, and said he understood the meaning of death for the first time.

He has every reason to be fearful. The UN's Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) says June saw the highest monthly civilian casualties in three years, with 232 people killed and over 1,300 injured.

Many will have been killed or wounded in communities close to the front lines, but others have been killed in cities far from the fighting.

"The surge in long-range missile and drone strikes across the country has brought even more death and destruction to civilians far away from the frontline," says Danielle Bell, head of HRMMU.

Reuters

ReutersModifications in the Shahed's design have allowed it to fly much higher than before and descend on its target from a greater altitude.

Its range has also increased, to around 2,500km, and it's capable of carrying a more deadly payload (up from around 50kg of explosive to 90kg).

Tracking maps produced by local experts show swirling masses of Shahed drones, sometimes taking circuitous routes across Ukraine before homing in on their targets.

Many – often as many as half – are decoys, designed to confuse and overwhelm Ukraine's air defences.

Other, straight lines show the paths of ballistic or cruise missiles: much fewer in number but the weapons Russia relies on to do the most damage.

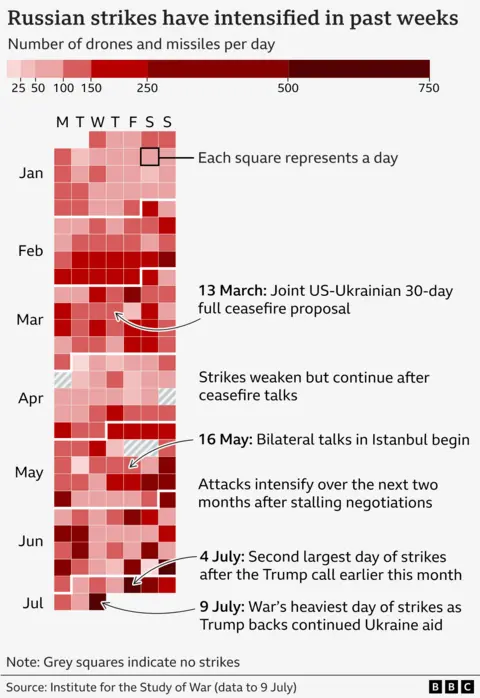

Analysis by the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War shows an increase in Russia's drone and missile strikes in the two months following Donald Trump's inauguration in January.

March saw a slight decline, with occasional spikes, until May, when the numbers suddenly rose dramatically.

New records have been set with alarming regularity.

June saw a new monthly high of 5,429 drones, July has seen more than 2,000 in just the first nine days.

With production in Russia ramping up, some reports suggest Moscow may soon be able to fire over 1,000 missiles and drones in a single night.

Experts in Kyiv warn that the country is in danger of being overwhelmed.

"If Ukraine doesn't find a solution for how to deal with these drones, we will face great problems during 2025," says former intelligence officer Ivan Stupak.

"Some of these drones are trying to reach military objects - we have to understand it - but the rest, they are destroying apartments, falling into office buildings and causing lots of damage to citizens."

For all their increasing capability, the drones are not an especially sophisticated weapon. But they do represent yet another example of the vast gulf in resources between Russia and Ukraine.

It also neatly illustrates the maxim, attributed to the Soviet Union's World War Two leader Joseph Stalin, that "quantity has a quality of its own."

"This is a war of resources," says Serhii Kuzan, of the Kyiv-based Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Centre.

"When production of particular missiles became too complicated - too expensive, too many components, too many complicated supply routes – they concentrated on this particular type of drone and developed different modifications and improvements."

The more drones in a single attack, Kuzan says, the more Ukraine hard-pressed air defence units struggle to shoot them down. This forces Kyiv to fall back on its precious supply of jets and air-to-air missiles to shoot them down.

"So if the drones go as a swarm, they destroy all the air defence missiles," he says.

Hence President Zelensky's constant appeals to Ukraine's allies to do more to protect its skies. Not just with Patriot missiles – vital to counter the most dangerous Russian ballistic threat – but with a wide array of other systems too.

On Thursday, the British government said it would sign a defence agreement with Ukraine to provide more than 5,000 air defence missiles.

Kyiv will be looking for many more such deals in the coming months.

EPA

EPA