Why should the new government spend money on science?

BBC

BBCWhen it comes to spending priorities, the new government has a lot to juggle - the NHS, social care, education, policing. So where should science rank on the list? Hundreds of thousands of people in the East are employed in science and technology industries. Many say supporting the sector is key to improving all of our lives.

In 2017 Fiona Barvé thought her fatigue was due to over-working but, when she developed mild abdominal pain, tests confirmed the A-level biology teacher from Saffron Walden, Essex, had stage 4 ovarian cancer.

“It was a colossal shock. It took me a year to fully understand what was happening,” she said.

Surgery was successful but the cancer returned in 2022. Mrs Barvé is now on a clinical trial, with a drug called olaparib keeping the cancer suppressed.

“It isn’t a cure because I don’t think we’ll get that, but it’s holding my cancer at almost 0%, and that’s great," she said.

"I’m so lucky to live near Addenbrooke’s Hospital. Not everyone in the UK has these opportunities. My concern is what happens when the trial ends, because there are funding implications of that.”

Trials are expensive, but so too is the research that precedes them, and much of it relies on public funding.

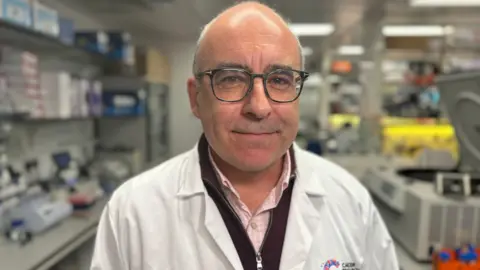

Cambridge professor Sir Steve Jackson came up with the idea for olaparib in the 1990s but, at that stage, it was too risky for big pharmaceuticals to invest in, so Cancer Research UK and the University of Cambridge stepped in to fund the venture.

“If my lab wasn't funded, and we hadn't made those discoveries, this drug wouldn’t exist. There are people walking around today who would have died," he said.

Prof Jackson is one of thousands of scientists on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus. He said, like many of them, he had to "constantly secure funding to keep the research going but every pound spent puts more back into the economy".

But the plea to the new government extends beyond money. Cancer Research Horizons was set up by the charity to help turn research into treatments. Its CEO, Iain Foulkes, said clinical trials must also be made easier.

“It's taken us two years to get a trial going, which is just too long. We simply don't have the NHS workforce to help set up and run clinical trials. They’re too busy with day-to-day duties," Dr Foulkes said.

"There’s also too much bureaucracy. We have to go through so many sets of approvals and it takes months. The pandemic was a good example of what we can achieve when we need to."

Cambridge has a global reputation for health research, but about 65 miles (about 100km) away Norwich Research Park is known for food science, and two start-up companies there are hoping they also get the government's attention.

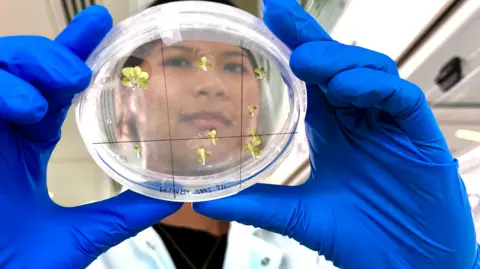

Alora describes itself as an ocean-agriculture company, which has "developed the world's most salt-tolerant crops" so they can grow on the surface of the ocean. It says it cuts the need for fertilisers and the use of fresh water for irrigation.

Alora

AloraCo-founder Rory Hornby said: "Seventy per cent of the world's fresh water is used for agriculture, leaving barely enough to drink, so what we're doing is good for the environment but it could also help tackle world hunger by improving access to nutritious food."

The crops can also be grown on land which has been written off for agriculture because of its high salt content.

Alora was set up in San Francisco because legislation governing plant breeding in the UK was "too restrictive". When those rules changed last year the company moved to Norwich, but Mr Hornby has urged the government to spread the wealth.

"Labour has announced a start-up/scale-up fund, which is great, but it applies only to the Cambridge, Oxford, London triangle, and the country has so much more to offer."

Alora's neighbour on the research park is PfBIO. It was created by Rosaria Campilongo to develop natural bacterial alternatives to chemical pesticides, which farmers are under pressure to reduce.

"Many crops, like strawberries, need spraying every week to keep pests and diseases away," she said. "We make the process more natural and reduce chemical residues on the fruit."

Dr Campilongo credits previous government funding, through Innovate UK, for getting her vision off the ground, but she wants the new government to speed up regulatory approval of agricultural products and to change the visa system.

"We want to recruit from Norwich and the UK but science is a collaboration and as a small company we can't afford to sponsor any scientists from overseas, which is a problem."

Funding for research and development will be set out in the next spending review, but a government spokesperson told the BBC that “life sciences is a true UK success story, driving economic growth and transforming healthcare".

The spokesperson added: "We will take a long-term approach to funding cycles, giving researchers the certainty they need, as well as setting out a plan to grow every part of the UK.

“The government will make it easier to conduct life-saving research with a quicker, more transparent and less bureaucratic process, positioning the UK to lead the world in clinical trials.”