Gas lamps still burn in unique area of England

BBC

BBCIt is almost 200 years since they were originally installed, but the gas lamps in a unique area of England are still burning.

The Park in Nottingham is thought to be the largest residential estate to still use this traditional technology.

British Gas has now taken over the care of the lamps and residents hope this will preserve them for years to come.

Andreas Liesche, who chairs the Nottingham Park Estate board and also lives there, said residents were "very proud" to still have this atmospheric type of lighting.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It just enhances the character of the estate," he said. "A lot of what we see in the estate is the very traditional, original construction, and it would have been illuminated all those years ago in very much the same way.

"It's a very quiet area to live, and of course the lighting gives that real characteristic of almost being in the countryside, despite being only a stone's throw from the city centre."

David Moody, operational heritage manager for British Gas, said "it was a massive boost" to be asked to take over the gas lamps.

"We've looked after the lamps in London for over 200 years, since they were first put in, so it's a privilege and an honour to be asked to take over Nottingham Park Estate," he added.

"The gas lamps were the start of the gas industry, and that's where British Gas evolved from, from the Gas Light and Coke Company."

Getty Images

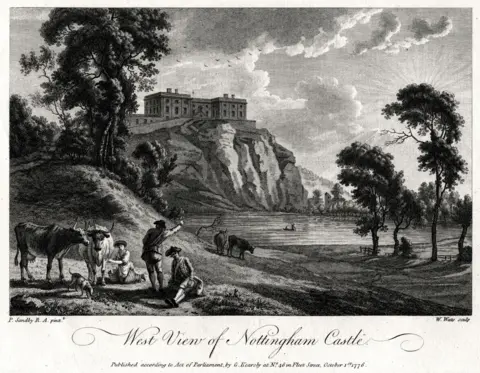

Getty ImagesWalking around the Park Estate feels like going back in time. Apart from the modern cars, much of it still looks as it would have done when the houses were built.

The private residential estate is situated to the west of Nottingham Castle and was formerly its deer park.

However, the first parcels of land began to be sold off in about 1800-1810 and homes were built from about 1830 onwards.

"The gas lighting, which is one of the largest networks in the UK and Europe, followed shortly afterwards," said Mr Liesche.

"So originally they would have been installed for horses and carriages.

"When the Park Estate was first created there were no cars, so it would have been horse-drawn carriages being pulled around the estate and the gas lighting was a means to allow them to navigate the area."

While the horses and carriages have long gone, the gas lamps have remained.

The estate's 3,000 residents - who have a say over how the area is run - feel it is important to preserve the historic lighting.

"There was a period when the gas lights were neglected in the 1970s, and prior to that as well, and there was a very positive drive to try to reinstate them and bring them back to their original use and beauty," said Mr Liesche.

But he said the lighting was not just there to look nice.

"One purpose is to make sure that the streets are appropriately illuminated, so that it's safe to walk around The Park," he said.

"What we want to do, without compromising anybody's safety, is make sure that The Park remains illuminated through its traditional means."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Moody said most of the UK's gas lamps were in London, but Nottingham was unique.

"Nottingham has got the largest residential estate that we're aware of, with 237," he said.

"There's some at the Black Country Living Museum, there's some in York around the cathedral, we've got some in Oldham we look after, a little estate in Norwich we look after.

"There's loads of little pockets everywhere. Europe's still got quite a lot; there are hundreds of them in Prague all around the main square, and Berlin."

Some of London's gas lamps have been under threat in recent years, as Westminster Council drew up plans to convert them to electric lighting.

But a group called the London Gasketeers has been campaigning to save them, and some have received Grade II-listed status.

Mr Moody said that while some people worry about the carbon footprint of gas lamps, light pollution from electric street lighting has been found to harm wildlife.

"We work really closely with Royal Parks down in London, and they have said since the London [gas] lamps have been brought back to how good they are now, they've seen an increase in bats and moths," he said.

Mr Moody said about 100 of the Nottingham gas lamps were still the originals.

"A lot of these lamps will be from the 1800s, and the others were later on, so 1900s up to 1950s they were still installing them," he said.

So what does caring for the lamps involve?

Mr Moody said they need regular servicing, as well as cleaning and repairing.

"The biggest threat for us is people knocking them over; lorries driving round that knock them over," he said. "It's quite common in London for us to lose a lamp."

Ryan Stanton, a technical repair engineer for British Gas, has been trained to repair and maintain the Nottingham lamps.

"It's a new qualification I've had to do, and I've had some on-site training with some of the lamp lighters that have come up from London," he said.

"I visit the estate a couple of times a week and during that time the on-site team will report any issues.

"I will go round and resolve those issues, and if there's no issues then I'll just do a service on the lights and make sure they're all in good working order."

Mr Moody believes the lamps are in safe hands for the future.

"Heritage is my job and we want to keep our history going," he said.

Follow BBC Nottingham on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.