The Russians using emojis to evade censors

Instagram

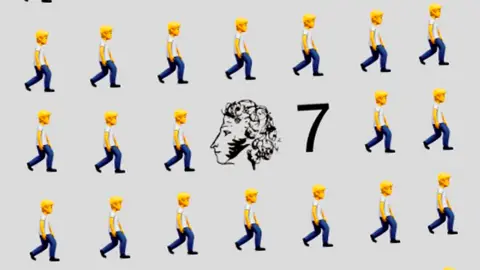

InstagramOn 24 February, as Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, an image started to spread on social media - a picture of the Russian poet Pushkin, the number seven and rows of the "person walking" emoji.

To those in the know, the meaning was clear - a location (Pushkin Square, in Moscow), a time and a call to protest against the government's actions.

The emojis made reference to a code used for years in Russia to refer to protests - one so well known to the authorities, it is barely a code at all, according to human rights group OVD-Info.

Why use code?

Unauthorised protests have been banned in the country since 2014 and breaches of the rules can lead to up to 15 days detention for a first offence. Repeat offenders can receive prison sentences of up to five years.

Since then, it has been common for activists to use various coded phrases to organise online.

"It's like, 'Let's go for a walk to the centre,' or, 'The weather is great for a walk,'" Maria says. This is what she will text her friends to let them know she plans to attend a protest.

What started as a way to evade government censors has almost become an inside joke or a meme, Maria tells BBC News.

Nevertheless, the consequences of not using this language can be serious.

What are the potential consequences?

Alexander attended a protest in Moscow, having posted about it on social media.

The following morning, plain-clothes officers picked him up outside his girlfriend's building and took him to the local police department. He was detained for several days and compelled to sign a document listing what the authorities said he had done.

We cannot be certain his attendance at the protest or his social media activity led to Alexander's detention. He was later arrested for a second time, while using the Moscow Metro, on a day he had not been attending a protest.

BBC News has learned of other detentions based solely on social media activity, including one woman arrested for a tweet.

On 24 February, she posted: "I haven't walked in the centre for a long time," and quoted another account's tweet containing a more explicit call to rally.

Five days later, she was arrested while taking a train.

She believes she was detected by facial-recognition software active on the Moscow Metro system - and in her court hearing, a document containing her tweet was presented, showing the authorities had taken a screenshot of it almost immediately after she had posted it.

In another case, Niki, a blogger, described how a close friend's brother had been detained twice - once for a few hours after attending a protest and a second time, for a whole week, for sharing the details with his friends on VK, Russia's equivalent of Facebook.

Almost 14,000 people have been detained across Russia since the conflict began a fortnight ago, mainly for attending protests according to OVD-Info - which provides legal advice.

So far, most have been held for a matter of hours or days.

Is the situation changing?

A law was introduced in Russia on Friday 4 March, with the stated aim of tackling "fake news" about the military but it is expected to be used to crack down even further on anti-war protests - including prison sentences of up to 15 years, significantly longer than previous sanctions.

For young people such as Maria, this has "already changed things, because now I'm afraid to go to protest and also I'm afraid to post about this 'special operation' [Russia's invasion of Ukraine]".

And there are clear indications arrests have increased since the new law was introduced, OVD-Info says.

Where are Russians now posting?

The shuttering of independent media outlets, blocking of Facebook and restrictions on Russians posting on TikTok have taken away key routes to access information, OVD-Info co-ordinator Leonid Drabkin says, and people will self-censor out of fear.

"Now if you go to your Instagram, there are like 10 times fewer posts," he says.

Many of his contacts have deleted their social-media profiles altogether.

And coupled with the stringent penalties, this has already affected the number of people "brave enough to protest".

Some contributors' names have been changed to protect their identities.