North Korea: Why doesn't it have enough food this year?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNorth Korea has suffered deadly famines in the past and now its leader, Kim Jong-un, has warned of severe food shortages ahead.

It's very difficult to get reliable information out of the highly secretive country.

The agricultural economy is still recovering from years of famine and mismanagement under Kim family leadership; and North Korea's "military first" ethos means that civilians are prioritised behind the armed forces for many resources, including food.

So what do we know about the food situation, and why might it be so bad this year?

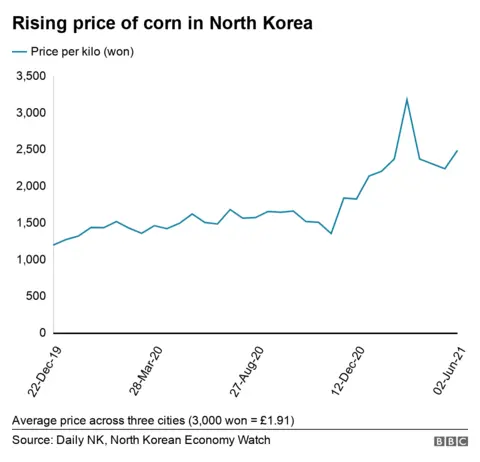

What's happened to food prices?

One of the clearest indicators of shortages is a rise in the price of basic foods.

The price for a kilo of corn (maize) rose sharply in February to 3,137 won (equivalent to about £2), according to data from the Daily NK website, which gathers information from contacts within North Korea.

Prices rose sharply again in mid-June, according to the Asia Press website, which communicates with North Koreans on phones smuggled into the country.

Corn is a less preferred staple than rice, but is often consumed because it's cheaper.

Meanwhile, a kilogram of rice in Pyongyang, the capital, is currently the highest it has been since December 2020 - but prices do tend to fluctuate.

Monitoring market prices provides some of the best data on economic activity, because most North Koreans get their food and other essentials from market trade, says North Korea expert Benjamin Silberstein.

"The state only provides a relatively small share to state bureaucracy employees."

State-supplied rations are barely adequate for most households, and are less reliable away from the major cities. This means many people rely on informal street markets to supplement their diets.

Severe weather has damaged crops

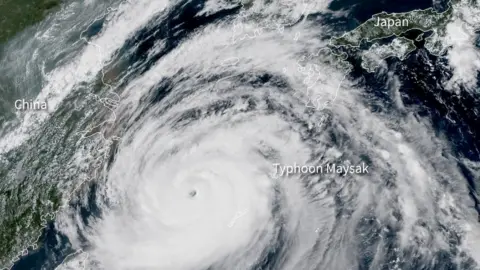

In his warnings of food shortages, the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, referred to the impact of typhoons and flooding on last year's harvest.

April to September 2020 was one of the wettest periods on record since 1981, according to the Paris-based agricultural monitoring organisation, GEOGLAM.

NOAA Himawari-8

NOAA Himawari-8The Korean peninsula was hit by a string of typhoons, including three which made landfall within the space of two weeks in August and September, a period which coincides with the start of the harvest of rice and corn.

Food can become scarce by June, as government supplies from the previous autumn harvest start to run low, particularly if harvests have been poor.

Typhoon Hagupit struck in early August and was one of the few storms in which state media offered a detailed damage report.

It said flooding had destroyed 40,000 hectares (100,000 acres) of cropland and 16,680 homes.

For later storms, state media largely avoided giving out much information.

The impact of these events has been made worse by decades of deforestation.

The economic crisis of the 1990s saw the widespread felling of trees for fuel, and despite regular tree-planting campaigns, deforestation continues, making flooding worse.

According to a report published in March by Global Forest Watch, 27,500 hectares (68,000 acres) of tree cover was lost in 2019, with about 233,000 hectares lost in total since 2001.

According to North Korea-focused blog 38 North, although the country has improved its disaster management, it's still woefully inadequate.

A serious shortage of fertilisers

One of the lesser-known problems for North Korea's agricultural sector is its difficulties getting sufficient fertiliser to improve crop yields.

KOREA CENTRAL TELEVISION

KOREA CENTRAL TELEVISIONA letter from Kim Jong-un in 2014 reminded leaders of the agricultural sector that they should find alternative easily-available sources of fertiliser.

"Use all sources of manure such as domestic animal excrement, night soil [human excrement], compost and ditch-bed soil [extracted from below the surface]" he wrote in the letter published by state news agency KCNA.

The country is not self-sufficient in fertiliser production, and according to Nikkei Asia in February, one of its major factories producing (among other things) fertiliser had to shut down due to a lack of spare parts.

That has been blamed on the closure of the border with its largest trading partner China in January 2020, because of the Covid pandemic.

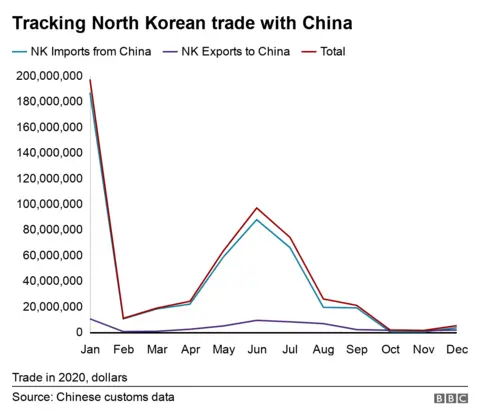

Trade is severely limited by sanctions

International economic sanctions means trade with other countries is already extremely limited.

Total Chinese exports to North Korea have ranged from about $2.5bn to $3.5bn in recent years. But last year the figure was less than $500m, according to Chinese official customs data.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSatellite imagery on both sides of the border (at Sinuiju and Dandong) shows a significant reduction in vehicle traffic compared with 2019.

It provides evidence to show the border has probably been closed to trade, according to a report by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

The researchers counted more than 100 vehicles in customs areas in September 2019 - but only 15 in March 2021.

Maxar (supplied by European Space Imaging)

Maxar (supplied by European Space Imaging)However, more rail carriages were sighted in March compared to photos of the same location in the past two years. which has led observers to believe more trade might resume.

Since then, there's been no indication the border will open properly any time soon, according to North Korea watchers.

Food aid problems

Closed borders have also made it difficult for North Korea to get food aid, which is exempt from the sanctions.

The country's biggest donor is China, and its food exports to North Korea have fallen by 80% since the start of the pandemic.

Aid flows into the country from donor nations have been inadequate for the last decade, the UN says.

And most international food aid organisations are currently unable to work in North Korea, with Covid restrictions making operations more difficult than normal.

Kun Li of the World Food Programme told the BBC that the WFP hasn't been able to conduct household food surveys since before the pandemic.

"Despite the challenges, in 2020, WFP brought in limited supplies and reached nearly 730,000 people... with food and nutrition assistance," she said.

DPRK GOVERNMENT

DPRK GOVERNMENTNorth Korea has a food shortage equivalent to about two or three months' supplies, according to a UN Food and Agriculture Organisation report.

"If this gap is not adequately covered through commercial imports and/or food aid, households could experience a harsh lean period between August and October 2021."

Reporting by Jack Goodman and Alistair Coleman.