Brexit: How many more EU nationals in UK than previously thought?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWednesday 30 June is the deadline for EU nationals living in the UK to apply for settled status, although the government says people with a reasonable excuse for delay will still be able to apply after that.

It is now clear that far more EU citizens have been living in the country than previous estimates suggested.

As of 31 May, the government had received 5.6 million applications for the post-Brexit scheme that allows EU (and EEA) nationals to continue living and working in the UK after the end of this month.

That is far higher than the official estimate when the scheme was fully opened in March 2019 that there were 3.7 million (non-Irish) EU nationals in the country.

About five million settlement applications came from England, just over quarter of a million from Scotland and about 92,000 each from Wales and Northern Ireland.

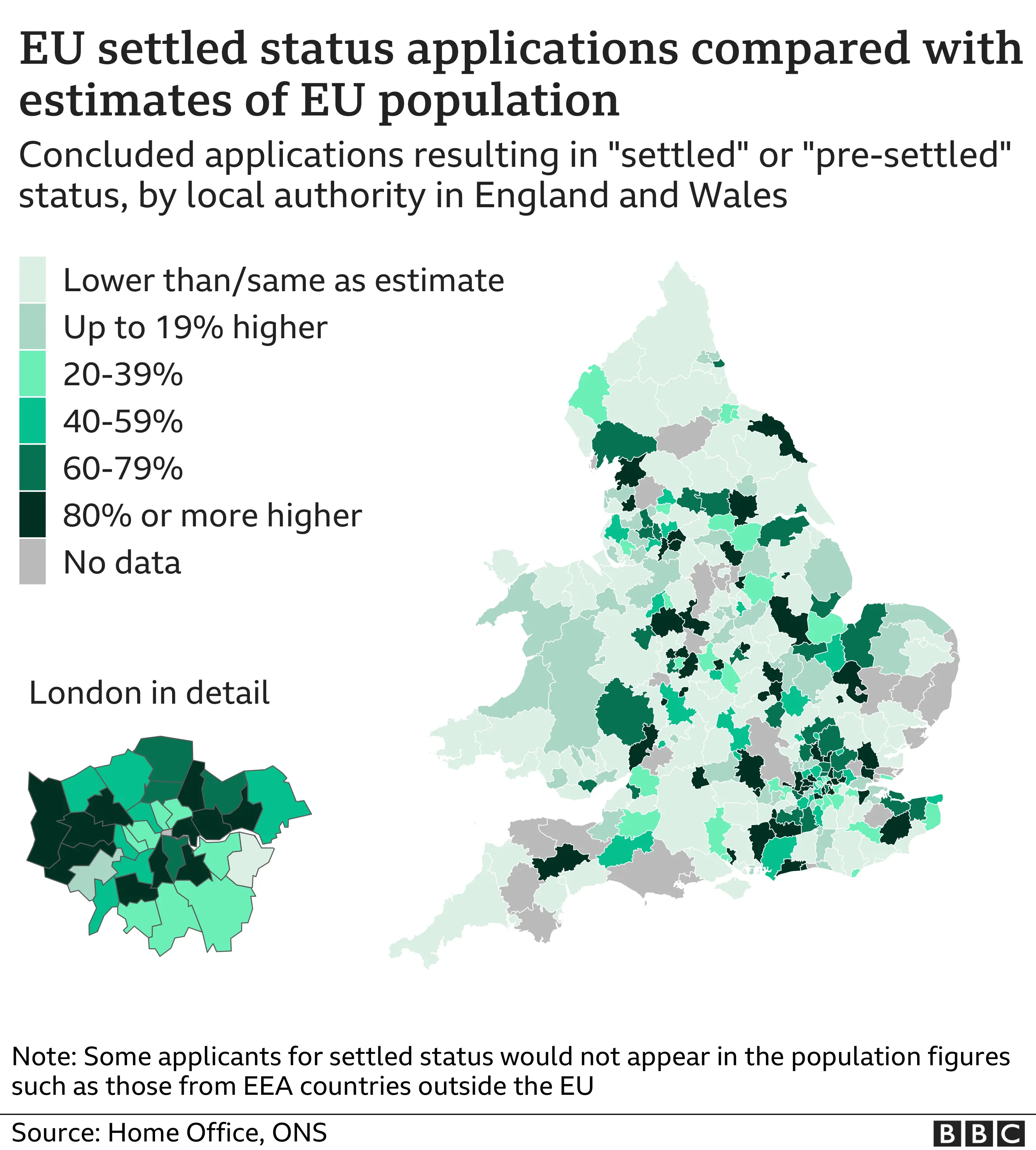

The latest figures for the scheme are broken down into numbers in each local authority in England and Wales. That allows us to make comparisons with the official estimates for the number of EU nationals in each local authority, to find out which areas those extra EU nationals may be living in.

It is not necessarily the case that all of the people who successfully applied for settled status are still in the UK.

The scheme has been successful, but has also highlighted how poor our understanding is of the number of EU nationals in the UK, with implications for both immigration policy and the labour market.

What is settled status?

EU nationals living in the UK have until 30 June to apply to stay in the UK. They can apply for:

- Settled status - on offer to anyone who can prove that they had been in the UK continuously for five years or more before 31 December 2020. As of 31 May, it has been granted to 2.75 million people.

- Pre-settled status - on offer to anyone who had been in the UK for less than five years by the end of 2020. As of 31 May, it has been granted to 2.28 million. They can apply for settled status in future, but there is no guarantee they will get it.

It is also important to note that smaller numbers of applications were repeats, invalid, or were rejected. And some non-European family members of EEA citizens can also apply.

In many areas, including parts of West Sussex, Wolverhampton and numerous London boroughs, the number of applicants was more than 80% higher than the estimated local population of EU nationals.

And some nationalities stood out. More than 760,000 applications have been approved for Romanians in the UK, for example, while the estimate of the resident Romanian population is only about 400,000.

What are the real numbers?

We don't know, but the settlement scheme has given us the best estimate we've ever had, because everyone has been asked to apply.

Even the pressure group formed in 2016 to campaign for the post-Brexit rights of EU citizens in the UK called itself The 3 Million. So, it wasn't just the government that didn't know the real numbers.

And it appears there may be between 1.5 and two million more people eligible for the settlement scheme than was initially forecast.

Migration experts say no big government scheme ever has 100% take-up. That means there could be tens or possibly hundreds of thousands of EU nationals who don't sign up to the settlement scheme.

They will lose certain rights such as the ability to work in the UK and claim benefits.

After the deadline, the government says immigration enforcement officials will begin issuing 28-day notices to people, advising them to apply for settled status.

Late applications will be considered if there are "reasonable grounds", but there is concern that vulnerable groups including children, elderly people in care homes, victims of domestic abuse and those with mental health problems will be disproportionately affected.

"The ultimate effectiveness of the scheme can only be judged when we know not just how many people successfully applied," says Catherine Barnard, deputy director of the think tank UK in a Changing Europe, "but how many of these hard-to-reach groups were left undocumented at the end of the process and how the government dealt with them."

Why were the estimates so wrong?

There have long been signs that the ways of working out how many people were migrating to and from the UK haven't been good enough.

The system relied on the International Passenger Survey, which involved the Office for National Statistics (ONS) asking travellers at UK ports whether they were planning to enter or leave the country for more than six months.

We have written about the flaws in this system before - the ONS itself has described it as being "stretched beyond its purpose".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe fact that more than five million people have now been approved by the settlement scheme highlights those flaws.

The other source of data that suggested the passenger survey might be underestimating European migration was National Insurance numbers, an issue we wrote about in 2016.

For example, while migration to the UK from the rest of the EU was estimated at 257,000 in the year to September 2015, 655,000 EU nationals registered for National Insurance numbers (Ninos) during the same period.

At the time, the ONS blamed short-term migration to the UK.

But now the ONS is working on a new way of calculating the numbers of people coming to the UK: the Registration and Population Interaction Database, or Rapid.

It involves looking at how people have been using the tax and benefits systems, including applying for Ninos, and it is no surprise that initial Rapid estimates for net migration are considerably higher than the official long-term international migration (LTIM) statistics.

The difference between the net migration estimates for those two methods is a total of 839,000 people since 2012.

The basic idea is that if somebody requests a Nino and starts paying taxes then they may have moved to the UK, and if they stop paying taxes for a prolonged period of time they may have left.

How many people are leaving?

Large numbers of EU nationals have left the UK in the last few years, a trend that began after the Brexit referendum and accelerated during the Covid pandemic. Both official statistics and anecdotal information acknowledge this trend.

And some economists warn it could have a significant impact on future growth.

Several sectors of the economy are reporting serious difficulties in finding new recruits, including drivers of HGV lorries, fruit pickers and people working in the hospitality industry.

It makes interpreting the data from the settlement scheme even more difficult.

"My suspicion is that a lot of people with pre-settled status may no longer be in the UK," says Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. "As the immigration statistics get better we should learn more, but not yet."

Additional reporting by Ed Lowther