Covid vaccines: Misleading claims targeting ethnic minorities

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere have been growing concerns about the uptake of Covid vaccines among black, Asian and other ethnic minority communities in the UK.

Some fear vaccine "hesitancy" could be increased by false and misleading information shared online. We've been investigating some examples.

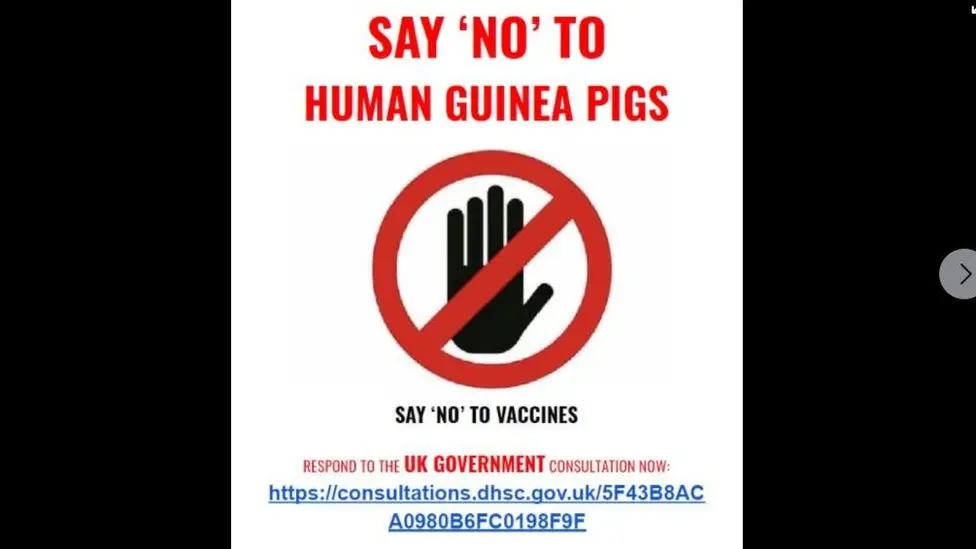

'Human guinea pig' claims

In the early months of the pandemic, a video was widely shared online of two French doctors discussing the initial testing of a possible vaccine in Africa first, before being tried elsewhere.

The comments, which led to an angry response on social media, fuelled existing concerns that Africans could be used as "guinea pigs" for a future Covid-19 vaccine.

But that didn't happen - vaccine trials got under way in sites spread around the world. The Oxford University vaccine team, for example, initiated testing in the UK and later in Brazil and South Africa. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine had clinical trial sites in Argentina, Brazil, Germany, Turkey, South Africa and the US.

Claims about vaccine priority list

In June, Health Secretary Matt Hancock announced initial advice from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) on who might be first in line for a vaccine, including health and social care workers and those at increased risk of serious disease from coronavirus.

He added that "we will continue to take into account which groups may be particularly vulnerable, including those from ethnic minority backgrounds. So we can protect the most at risk first should a vaccine become available".

But his comments were greeted with suspicion by some and sparked more claims about ethnic minority people being used as "guinea pigs" for the vaccines.

A black British woman posted a video in June saying, "why should these vaccines be trialled on me and my people".

In the end, ethnic minority groups were not included on the priority list, which includes the elderly, those in care and frontline health workers.

The video - which has had around 50,000 views - also falsely claimed that people had already died from the "trial vaccines". There were no deaths caused by vaccines administered during the Pfizer and Oxford trials.

Want to know more about vaccine safety?

- Read this article from the BBC's Health team on how we know the vaccines are safe.

- You can also find out who gets the vaccine first and why.

- How effective is the Oxford vaccine and how does the Pfizer vaccine work?

- Vaccine Q&A in five South Asian languages

Vaccine ingredients

Some of the most persistent myths surround the contents of the vaccines.

We've previously dealt with false claims that they contain microchips, aborted fetus cells or that they can somehow alter our human genetic code (DNA). None of these are true.

But there have also been specific concerns over whether they may contain ingredients that are forbidden under religious beliefs.

Rumours that vaccines contain traces of pork (not eaten by Muslims) or beef (cows are considered sacred by Hindus) have been circulating online, particularly within South Asian communities.

It's true that some other non-coronavirus vaccines have contained gelatine derived from pork, added as a stabiliser. However, none of the Covid-19 vaccines currently approved for use in the UK contain gelatine.

In fact, the body that approves vaccines has made it clear that the Moderna, AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines "do not contain any components of animal origin."

"We need to be clear and make people realise there is no meat in the vaccine, there is no pork in the vaccine," says Dr Harpreet Sood, who is leading an NHS anti-disinformation drive.

He adds that this "has been accepted and endorsed by all the religious leaders and councils and faith communities".

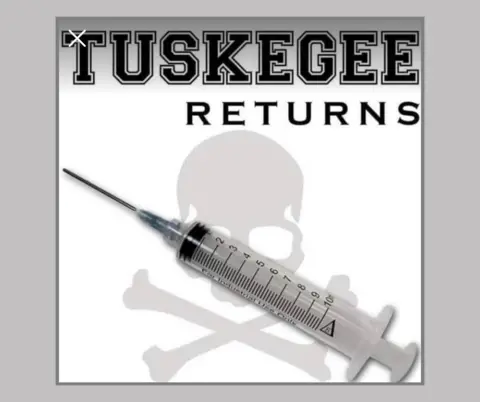

A history of unethical experimentation

Some of the anti-vaccination discussion online has referenced cases of mistreatment of black people by the medical establishment in the past.

The Tuskegee scandal is one example. From the 1930s, and lasting for several decades, hundreds of African American men had their syphilis left untreated without their knowledge as part of an experiment.

Dozens suffered terribly and died and the case remains one of the worst examples of racism from the field of medical research.

More recently the case has been used to stoke fears about medical malpractice in the black community online.

There is of course no evidence of any unethical practice in any of the vaccine trials. The teams behind the research say they have ensured a diverse range of trial participants. To take the example of the Pfizer trial in the US, 10% of participants were black, 13% Hispanic, 6% Asian, 1.3% Native American, with the rest white.

"While it's important to acknowledge unethical experiments on black people, to ensure those in power don't let it happen again, using these examples to deter people from taking the coronavirus vaccine is exploitative," says Dr Winston Morgan, reader in toxicology and clinical biochemistry at the University of East London.

"Trying to compare what happened [then] to what's happening now is wrong."