Chile's protest street art: The writing is on the wall

BBC

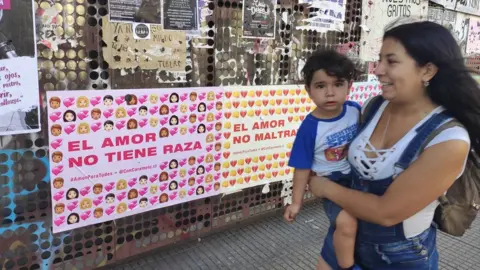

BBCThe walls of the streets of downtown Santiago are covered with stickers, art, words and posters.

The messages are varied and range from "Feminist power" to "All cops are bastards". They have taken over the walls of Zona Cero (Ground Zero), the name given to the area around Plaza de la Dignidad, where anti-government protests have been held - and at times brutally repressed by police - since 18 October.

The protests were originally triggered by a rise in the metro fare in the capital, Santiago, but soon became a much wider movement denouncing inequality in Chile, the high costs of healthcare and poor funding of education.

BBC

BBCThe slogans daubed on the walls, such as "Piñera must quit", reflect some of the anger at the government and the President, Sebastián Piñera, which many Chileans are expressing.

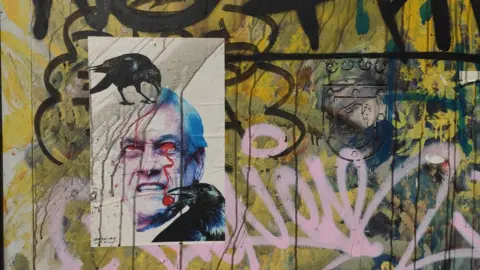

Óscar Núñez has been at the forefront of the protests since they first started. A graphic designer, he decided to use his experience to make street art under the name of Mr Owl.

He says that street art offers a non-violent way of creating a dialogue between him and others. "I started using the image of a military officer in a peaceful yoga pose. It's ironic and fresh but my favourite part is that other graffiti artists have put their own touches to that image," he says.

BBC

BBCHe explains that people would paint the eyes red in a reference to the hundreds of protesters who have been blinded by projectiles shot by police.

Potent message

Graffiti and street art has a long tradition in Santiago, where it was widely used in the 1970s to protest against the military rule of Gen Augusto Pinochet and to foment radical social change.

BBC

BBCEver since, all kinds of graffiti - urban, feminist, political and social - have flourished here.

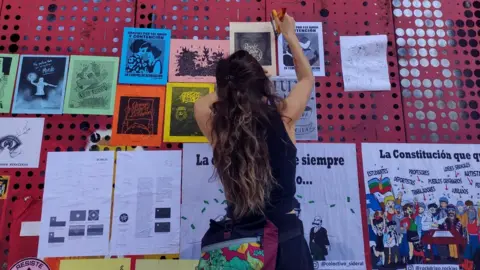

But 39-year-old street artist Caiozzama says that before the current wave of protests, it was mainly confined to certain areas of Santiago. "To see so many right downtown wasn't common," he explains.

BBC

BBCCaiozzama has been a street artist for the past six years. He says that while he tackled more global themes such as climate change before the current wave of protests, his art now centres on Chile's political crisis. "Nonviolence is a potent message that needs to be remembered right now," he says.

And it is not just graffiti which is flourishing - performance art and music are also integral parts of the protests, with Chilean feminist collective Las Tesis' performance against sexual abuse going viral and being recreated as far away as Turkey and France.

Remove or keep?

But the graffiti poses a dilemma for the owners of buildings and businesses on which it is painted. Keep it in a show of support or clean it off? The municipal authorities try to cover up the political messages whenever they get a chance.

BBC

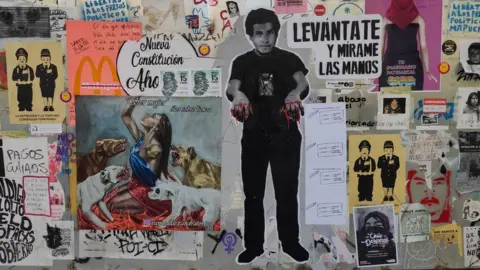

BBCAlejandro Conteras, 33, is a protester and photographer whose large prints adorn the facade of the Gabriela Mistral cultural centre in Santiago.

He says that the walls of the city have become a canvas where subjects that are not covered by the country's media can be tackled. "The press won't talk about the protests? Then we will do the task ourselves."

BBC

BBCLoreto Pavez, a 41-year-old illustrator who started dealing with political issues in her illustrations in October, agrees. "The government wants to make us believe that everything is just fine in Chile. But we won't stop spreading the message of what's actually happening here," she says.

"We don't work as a collective, but we do try to show the diversity of voices behind the protests," fellow illustrator Alexandra Gross, 30, says of their posters which include text in Mapudungun, an Araucanian language spoken by the Mapuche, the largest indigenous community in south-central Chile.

'True expression of the people'

Earlier this month, the murals which covered the facade of the Gabriela Mistral centre were painted over by unidentified people overnight.

Hours later, dozens of artists turned up and again filled this now blank canvas with drawings, but the incident showed how easily street art can be erased.

BBC

BBCThe Museo de la Dignidad (Museum of Dignity) is an artists' collective which tries to counter attempts to erase political street art by "framing" the best pieces by placing wooden gold-coloured frames around them.

"The golden frame has provided street art pieces, which are essentially ephemeral, a sense of protection to help them survive censorship or hatefulness" explains Rulo, 39, one of its members.

The discussion surrounding street art has also wound its way into Chile's venerable National Museum of Fine Arts.

BBC

BBCRight in the middle of its main hall, the museum has placed a pinboard asking visitors the question: "In your opinion, what should the museum do about the graffiti on its facade?"

The answers are diverse and range from "It's not art" to "It's the true expression of the people" while others propose for the graffiti to be photographed so it can be kept as evidence for future generations.

With the protests far from abating, Santiago's street art and its merits are likely to divide Chileans for a while to come.

All photos by Gabriela Mesones Rojo and subject to copyright.