General Election 2019: What is Labour's economic plan?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLabour's chancellor John McDonnell has unveiled a plan which it promises will deliver a "irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people".

So what is the party's plan?

1. Doubling investment

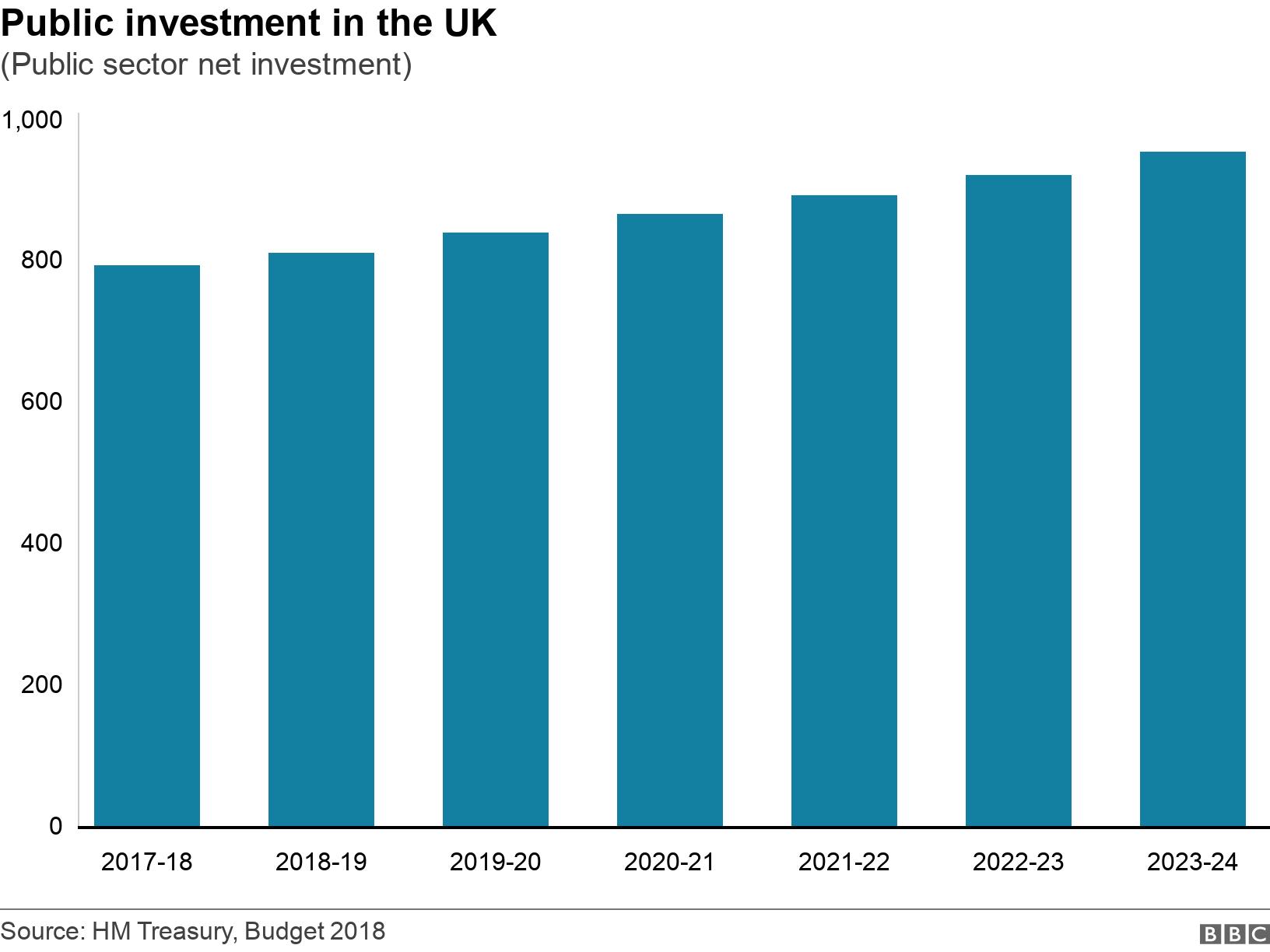

Labour want to spend a lot more money. They want to double "investment" spending - money spent on long-term projects, as opposed to day-to-day expenses such as paying civil servants' salaries.

An extra £55bn a year on investment is certainly a huge amount of money. For comparison, the government was expected to spend £48.4bn on investment this year, according to the 2018 Budget.

Capital investment in health this year is set at £6.7bn, and for education it is £5.1bn.

2. Two funds

Under Labour, there would be a £150bn "social transformation fund". This would pay for upgrades to schools, hospitals, social care facilities and council homes and would be spent over five years - an average of £30bn a year.

In addition, a £250bn "green transformation fund" would be spent over ten years, averaging £25bn a year. This would be spent on projects to improve sustainability, such as energy and transport, and insulating existing homes.

3. Infrastructure

There is no doubt a long list of things in the UK which could do with improvement. To take the example of schools, a National Audit Office report in 2017 found that there were 178 schools in the UK in poor condition.

The report found that it would cost £6.7bn to upgrade all the schools in England to a satisfactory condition, and another £7.1bn to upgrade them to good condition.

However, the UK is already undertaking a number of significant construction projects - Crossrail, the Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, and HS2.

Finding qualified workers to undertake more infrastructure projects would not be straightforward.

Infrastructure projects take years to plan and approve before the first concrete gets poured. Experts warn that finding enough projects which are ready to start and offer good value for taxpayers' money might be problematic for whoever wins the election.

"If you promise more than is deliverable then you risk wasting money, however good the long-term intention is," said Paul Johnson, director of the IFS.

Reality Check looked at the difficulties of investment spending here.

4. Moving power to the North

John McDonnell says he wants to achieve "an irreversible shift in the centre of gravity in political decision making and investment" away from London to the North and other regions of the UK.

The National Transformation Fund will be managed from a new department of the Treasury, based at an unspecified location in the North of England. And an element of the fund would be specifically managed and spent locally.

As this report shows, only a minority of civil servants - 83,500 out of 430,000 - are based in London. More than 50,000 are already based in the North-West.

However, the majority of Treasury staff, and the most senior staff, are currently based in London.

5. University tuition fees

On top of its investment plans, Labour promises to make university tuition free, as the party did in its 2017 manifesto.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies said at the time that scrapping tuition fees would add an extra £11bn a year to the amount the government has to borrow.

In this election, the extra cost of doing this instead of keeping tuition fees at their current level of £9,250 would be lower because of a change in the way student loans are treated in the national accounts.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs much as 45% of student loans will never be repaid, and this now has to be counted as government spending.

You can read more about the changes in this piece.

6. Decarbonising

Mr McDonnell said the National Transformation Fund would allow Labour to "decarbonise as thoroughly and fast as our commitment to a just transition will allow".

In other words, it would reduce the amount of greenhouse gases the country produces.

The most dramatic element of the plan announced so far is a scheme to improve the insulation of 27 million homes, which it estimates would cost £250bn, though only £60bn of that would come from government grants.

It would increase investment in rail and offshore wind.

7. New rules on borrowing

In its 2017 manifesto, Labour said it was "committed to ensuring that the national debt is lower at the end of the next Parliament than it is today".

Called the fiscal credibility rule, this commitment is designed to reassure investors that Labour is a reliable steward of the economy and would not let debt spiral out of control.

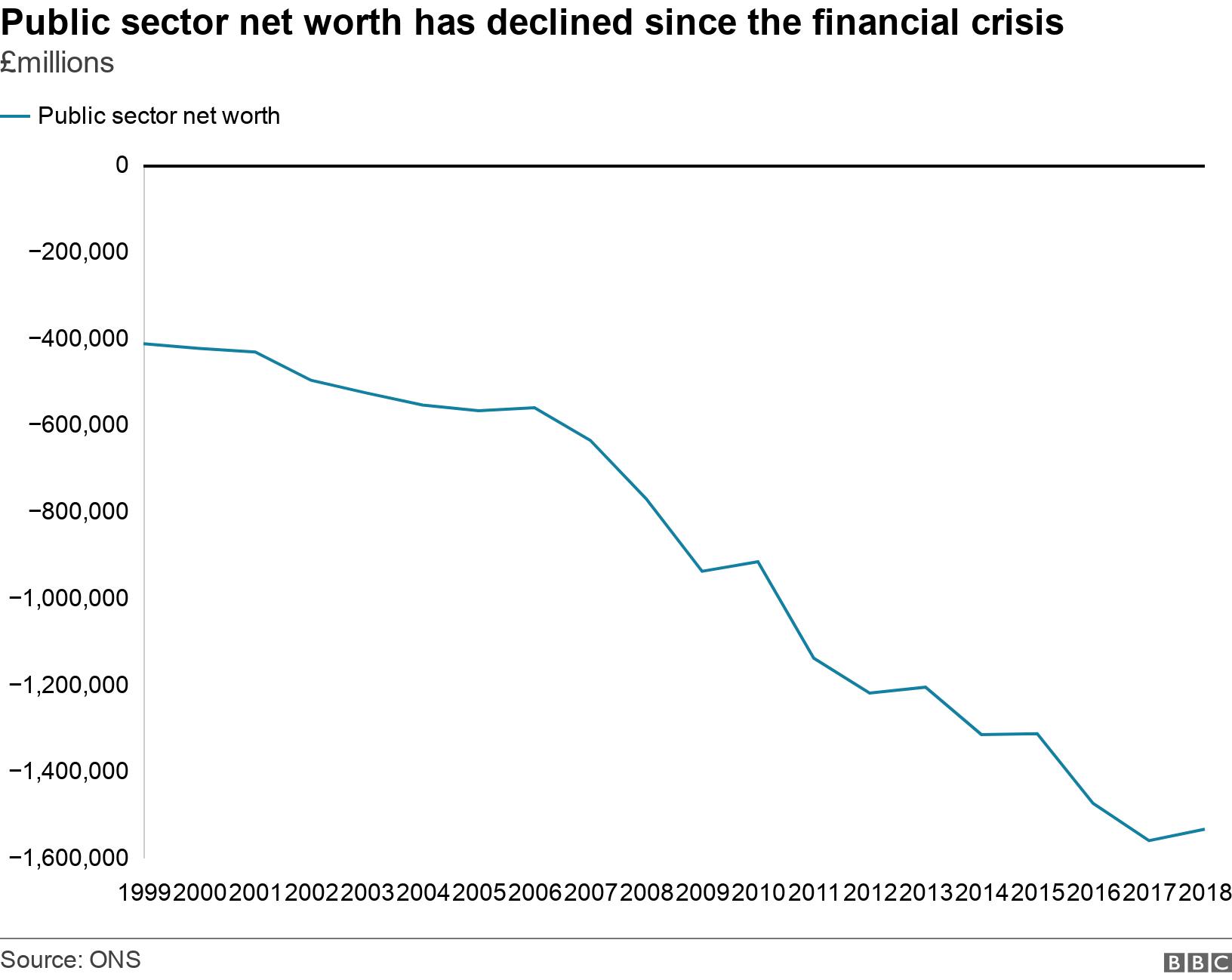

On Thursday Labour said its target for borrowing would change significantly. Instead of promising to reduce the national debt, it would seek to improve "the overall balance sheet". Instead of targeting the national debt, they are targeting a different statistic called "public sector net worth".

Though it sounds similar its consequences in practice would be profound. At the moment, if the government borrows £1m to build a road, that counts as £1m more added to the national debt.

But under the new rule, the government now owns a new road which would be worth around £1m. The value of the new asset - the road - balances out the new debt, and public sector net worth hasn't changed at all.

This means the government can borrow much more than it would have done under the old rules, as long as it uses that money to invest in an asset.

Labour's plan to borrow an extra £55bn a year for the National Transformation Fund would have been next to impossible under the old rule.

Also Labour's plans to borrow to nationalise some public utilities would be affordable under this plan, as they would bring the government an asset as well as a debt.

Affordable, that is, as long as the government can find someone to lend it the money.

8. Will it be possible to raise all this money?

Labour has said that it will fund this extra spending by borrowing money. It will issue long-dated government bonds - IOUs which attract an interest rate, but won't have to be paid back for many years.

The government can currently borrow for 30 years for an effective interest rate of 1.25%, and many economists argue that it makes sense to borrow at such low rates for projects that will give a bigger return than it costs to fund them.

It is likely that bond markets would be willing to lend the government this money, though the effective interest rate that investors demand might well rise as borrowing increases.

The influential bond investor Pimco told the Financial Times that the UK was one of its "least favourite" markets to invest in, because of the combination of low rates and big public spending increases in prospect. But even they did not expect a big increase in government borrowing costs.

9. National investment bank

The National Investment Bank was an idea that also featured in Labour's 2017 manifesto, which it is committed to again.

The bank would have £250bn of lending power over 10 years and would target small businesses that support the government's industrial strategy (such as energy-efficient housing and decarbonisation).

While the bank would require an initial cash injection from government funds, Labour believes it would able to fund itself in the longer run. This could be done, for example, by raising money from outside investors.

10. More tax for the top 5%

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn said the party's tax plans "will affect 5% of the population - the rest of the population will benefit from it". So how much do you have to earn to be in the 5%?

HMRC figures from 2017 indicated that the top 5% of taxpayers earn more than £75,300. That's in line with Labour's previous remarks implying that "the rich" are those earning more than about £70,000-80,000 a year.

How many people is that?

HMRC says that there were 31.2 million taxpayers in 2016-2017, so the top 5% being targeted would be about 1,560,000 people.

"Taxpayers" covers most working people, but not anyone who earned less than the personal tax allowance of £11,200 that year.