Mushy ice and lost kit: The scientists studying Antarctica as it melts

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith Antarctica's climate warming at an unprecedented rate, scientists are battling with dangerously thin ice and equipment falling through into the sea beneath.

For 20 years, Simon Morley has been cutting holes in Antarctic sea ice and diving into the frigid waters below to study strange and colourful sea life – including sea squirts and sponges. But climate change is thinning out this ice, meaning it is often no longer safe enough to travel over.

"'We'd get 100 or more dives through the sea ice in the winter period [in the past]," says Morley, a marine biologist with the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). "Last year, I think [my colleagues] managed maybe five to ten dives through the sea ice."

The ice is creating a Catch-22 situation. "It's too thick for them to get the boats out but it's not thick enough to cut holes in with the chainsaw and actually do the diving," he explains. A helpful way around this, however, is to keep boats ready and standing by during the winter, so that they can launch immediately when a window opens to use them, he says.

Getty Images

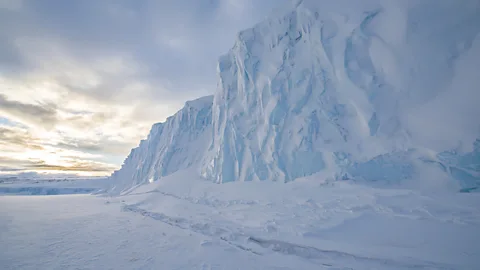

Getty ImagesWe tend to think of Antarctica as a perennially ice-bound world. But while the continent remains a challenging and inhospitable environment for humans, it is changing. The volume of frozen water in Antarctica is plummeting, vegetation is spreading across the landmass and air temperatures are rising.

The scientists who study Antarctica and the organisms that live there have noticed these changes. Not least because their jobs are getting more difficult.

"The glacier that I learnt to ski on in South Georgia is no longer a glacier, it's not there anymore," says Morley, who has worked in Antarctica since 2005. Instead the island, which lies northeast of the Antarctic Peninsula, has gained areas of bare ground and patches of invasive meadow grass have appeared there. Now that it is no longer possible to carry out so many dives throughout the year to study life in the seas, he and his colleagues are trying to carry out those dives in clusters during the summer and winter, which allows them to make seasonal comparisons instead of performing continual monitoring.

What's the hurry?

One reason scientists are interested in Antarctic ice is to study past patterns of climate change. Research activities such as taking ice cores, which are composed of layers of ice laid down millennia ago, can reveal what global temperatures were like at the time. And trapped pockets of gas in those cores can be analysed to help us understand how the makeup of the atmosphere has changed. However, these precious records are threatened by the retreat of glaciers and the warming of polar regions. The pressure is on to collect as much data as possible before it's too late. You can read more about the ancient memories trapped in the world's ice in this article by Lou Del Bello.

Morley enthuses about the extraordinary species that he has seen on his trips: "Amazing sponge, anemone and sea squirt gardens – they're absolutely incredible." However, these underwater wonderlands are at risk.

Now that there is less ice covering the cold waters where these animals live, algae that blooms with the increasing levels of light from above is spreading and threatening to smother the sponges and similar lifeforms, says Morley. In May, he and colleagues published a paper noting that these creatures face an additional climate change-related problem: there's a rising risk of huge, moving chunks of ice ploughing into the seafloor where they live.

Another researcher at the BAS, sea-ice physicist Jeremy Wilkinson, says that he has had to adjust some of the experiments he carries out in the other polar region, the Arctic. This is because sea ice there is far less reliable than before. When the climate was cooler, he and colleagues used to place waterproof suitcases on the ice with instruments able to track things such as wind speed and temperature over the course of a year.

"Now, with the ice retreating so fast, we can't do that because the ice melts and your instruments drop into the ocean," says Wilkinson. "All our systems are now designed to float."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBack in Antarctica, the lack of sea ice in the southern hemisphere winter has startled Natalie Robinson, a marine physicist with New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

She and colleagues use satellite imagery to keep an eye on ice formation in McMurdo Sound, a body of water on the Antarctic coast directly south of New Zealand. "In 2022, we had a winter growth season [the period in which ice cover is usually expanding] that no one had ever seen anything like before," says Robinson. "As late as the end of August we still had open water."

While sea ice did form in McMurdo Sound in the following weeks, it never got thick enough to allow Robinson and her colleagues to carry out their planned experiments in certain locations. In some areas of McMurdo Sound, other researchers were able to transport scientific equipment over the ice on foot. With ice that was only around 1.1m (3.6ft) thick – roughly half as thick as usual – it was judged too dangerous to drive. It was the first time the team of New Zealand scientists have had to transport their equipment on foot.

"We describe that season as unprecedented, but pretty much exactly the same thing has happened two years later," says Robinson, of the situation in 2024.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor seven years, Robinson has been hoping to use an ice-coring system to study platelet ice – a fuzzy-looking mass of ice crystals full of seawater-filled cavities – which forms on the underside of sea ice. She and her colleagues have designed an ice-coring system that would allow the scientists to retrieve this delicate kind of ice intact, so that they can study its structure and also observe how lifeforms may dwell within it.

Robinson's intention had been to take such samples from sea ice near to the Ross Ice Shelf, a giant ice shelf with an area of more than half a million square kilometres (200,000sq miles). However, the unfavourable weather conditions meant that they couldn't get out to the desired location, and instead had to sample ice much closer to Scott Base, New Zealand's Antarctic research station. "It was effectively a whole different part of the ocean we were studying," she says. "Not at all what we were planning."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe problem is not just that warmer temperatures are hampering ice formation, it's also that storminess appears to be increasing in the Southern Ocean, which churns up ice and prevents it attaching securely to land, says Robinson. This storminess has other implications, too: "If we're looking at a windier general setup, it's definitely going to make any of the fieldwork that we do much more challenging," she says.

Robinson explains that her experiences in Antarctica during the past 22 years revealed to her what a dramatic impact climate change is having on the continent. She describes what she has seen as "sobering".

That said, in her career, Robinson has noticed public attitudes to climate change evolving. Climate change denial seems to her less widespread than it once was, for instance, she says: "That, certainly, is hopeful for me."

However, time is running out to perform certain scientific experiments in Antarctica, meaning the next few years will be crucial. Potentially, some fieldwork will no longer be possible if huge swathes of sea ice disappear entirely.

"We're racing to gather all the data we can," adds Robinson, "Before those major shifts happen".

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.