Spies, bikes and smuggled ink: Fighting pollution and the Stasi in the shadow of the Berlin Wall

The Stasi Records Archive

The Stasi Records ArchiveFormer dissidents, released secret service files and a zine in an East Berlin basement reveal a little-known chapter of Cold War history.

East Berlin, late November 1987, around midnight. In the basement of an old tenement building, 14-year-old Tim Eisenlohr is stapling pages coming off a printer smuggled in from the West. He and his friends are publishing a semi-legal magazine about the environmental problems plaguing their Socialist state, the German Democratic Republic: air pollution, dirty rivers, acid rain and hazardous nuclear reactors. Cut off from Western Europe by a fortified border with a death strip, and separated from West Berlin by the Berlin Wall, they are trying to spread information the East German censors don't want anyone to see.

Suddenly, the door flings open, and "around 15 armed members of the Staatssicherheit burst into the room, some with their guns drawn, led by a prosecutor", recalls Eisenlohr, referring to the East German secret police, also known as the Stasi. "They call out: 'hands up, switch the machine off, stand against the wall!'"

The men search and photograph the room, confiscate the printer – and then one of them utters the Stasi's notorious, cryptic line used to take away people for interrogation: "You're summoned to clear up an issue." One by one, Eisenlohr and the others are bundled into cars and taken to the Stasi's headquarters.

Named "Operation Trap", the raid and arrests were part of the Stasi's attempts to crush a group of people fighting for a cleaner environment – and for the right to speak out. The secret police's tactics ranged from interrogations and jail to bizarre mind games. In one incident, informants who managed to infiltrate the environmental movement covertly took coffee from a shared pantry without putting money into the coffee kitty. It was a psychological manoeuvre, aimed at sowing conflict and mistrust within the groups.

That plan did not work out – neither the psychological manipulation, nor the dramatic crackdown. On the contrary: Operation Trap became one of the very rare cases in history in which the Stasi was forced to back down. Standing against them were a tiny group of self-described peaceniks and eco nerds, who printed a magazine with a run of just a few hundred copies, and regularly ran out of ink. At one point, the US Congress even weighed in and sided with the producers of the little magazine. How did it all happen?

Interviews with dissidents from that time, and internal reports from the Stasi's secret archive, which was opened after the fall of the Berlin Wall, tell the surprising story of how a small environmental movement managed to take on a powerful dictatorship – and ultimately, won.

Tim Eisenlohr

Tim Eisenlohr"I actually grew up as a very normal child in the GDR, but in a family where we were encouraged to ask questions," says Eisenlohr. His parents had grown sceptical of the regime. The family loved animals, and their flat in Berlin was always filled with "something fluttering about" he recalls – rescued birds, and once, even a pig. Eisenlohr spent as much time as he could outdoors, watching birds and beavers, camouflaging himself with a bedsheet in winter to observe animals in the snow.

In theory, such a passion for nature should have been in line with East Germany's stated goals: looking after the environment was enshrined in the GDR's constitution. In practice, however, state-owned industries and the heavy use of lignite (brown coal) as an energy source polluted the air and water. The pollution was so bad that it harmed people's health, and East German children grew up with poorer lung function than those in West Germany. Of course, democratic countries in the 1980s also had environmental scandals: West Germany dumped toxic waste in East Germany; French intelligence agents bombed a Greenpeace ship to clear the way for nuclear tests.

But in East Germany, without a free press or freedom of opinion, highlighting even basic environmental problems was taboo. On days when West Berlin imposed a smog alert due to high levels of pollution, a newspaper in East Berlin reported "cloudless skies and sunshine". Environmental data was considered a state secret in East Germany, activist gatherings were banned, and criticism of the state was punishable by up to 10 years in jail.

"The basic formula of any dictatorship is, firstly, spreading lies and suppressing the truth. And secondly, destroying any kind of solidarity, so that in the end, you don't even care anymore if your neighbour is arrested, and you just keep quiet," says Christian Halbrock, one of the co-founders of Umweltblätter, the environmental zine printed out of the tenement building basement in East Berlin that Eisenlohr helped to publish. "We didn't want to live with those daily lies, we wanted to live with the truth, and to show with our own, authentic, truthful lifestyle that we were serious about that."

Getty Images

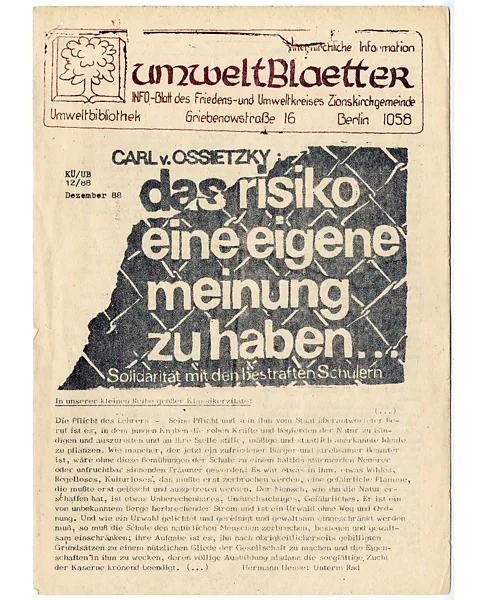

Getty ImagesThe Umweltblätter – German for "environmental pamphlets" – were an attempt to counter the pervasive misinformation with facts. Its headlines spanned from "Baltic Sea: The nation's sewer", to "Chernobyl is everywhere" (about the risk of nuclear energy), to tackling free-speech issues.

To print magazines or books for the general public in the GDR, one had to apply to the authorities for a printing licence and was then given paper. Since that licence, and therefore paper and ink, could generally only be obtained for state-approved publications in East Germany, producing any alternative media was difficult even before the actual censorship process set in.

The Umweltblätter zine circumvented this effective ban of free media: it was printed in a basement belonging to a liberal pastor at the nearby Zion Church, and carried the line "for internal church use only". As part of a compromise with the state, churches were allowed to print internal documents. In reality, the magazine was circulated widely, passed from hand to hand, and read far outside Berlin. The ink was smuggled in by visiting supporters from the West. (Though once, according to Halbrock, one of the East German activists posed as a member of the Young Pioneers, a state-controlled youth movement, and successfully asked GDR manufacturers for ink samples for his Pioneer project.)

Also in the basement, and run by the same activists, was an environmental library open to the public, with books were smuggled in from West Germany. "We were always trying to push the boundaries of what was possible," says Eisenlohr.

Elsewhere in the GDR, people were also testing the state's boundaries with environmental action, be it by planting trees, collecting rubbish or cycling through cities to protest against air pollution and promote car-free transport. The Stasi had its eyes on all of those groups, including a surveillance operation against the cyclists code-named "Ventil" or "Valve", as in, bike valve.

Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft

Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft"Unlike today, where climate change still feels a bit abstract for many people, back then, we could feel the destruction with all our senses," recalls Gisela Kallenbach, a chemical engineer who worked at a research institute in Leipzig, and was both an environmental activist and a member of a progressive church community. "We could basically taste the sulphur dioxide in the air, we could see the smog, we could smell the rivers that had been turned into open sewers. We couldn't ignore it, it was with us every day."

However, even cautious attempts to highlight these issues could have dramatic consequences.

In 1983, Kallenbach and a colleague put together a poster about smog pollution and hung it in the corridor of her institute. Knowing that environmental data was considered a state secret, she only used facts from scientific books already published in the GDR. That way, she thought, she could not be accused of publishing secret data. In any case, the poster was internal and would only be seen by people at the institute.

"Usually, no one looked at those internal posters, but the news of this one spread like wildfire. People started crowding around it," she remembers. After two hours, an order came from a socialist party official to remove the poster. The next day, Kallenbach and her colleague were summoned by the official and asked to apologise. She saw no reason to apologise for showing scientific facts, and refused to capitulate, she says. The Stasi put her under surveillance in response, along with other activists. As her environmental and peace activism grew, the secret police eventually put Kallenbach on a list of people of people who would be sent to internment camps in the event of a government crackdown. She was also given a veiled threat that her three children might suffer if she continued to speak up.

"It wasn't only about protecting the environment," says Kallenbach. "Because of the way the state tried to repress us, it was also about basic human rights, about questions like, 'Can I state my opinion freely? Can I share facts about our situation? Or is all that persecuted and punished?'"

It was in this pressure-cooker atmosphere of growing opposition, and heavy-handed suppression, that the Stasi put together Operation Trap.

Robert-Havemann-Gesellschaft

Robert-Havemann-GesellschaftAt the age of 14, Eisenlohr was the youngest member of his group but had already experienced years of friction with the state. It began when he was eight years old and watched a US TV series about the Holocaust broadcast on West German television, which many East Germans were able to secretly watch. Wondering how humans could stand by while others did such evil, he began noticing some worrying parallels to his own society.

"The Nazis were a different level of evil, no doubt, but it irritated me that we, who were supposed to build a new Germany, were using some similar methods," Eisenlohr says. Specifically, the pressure to conform from early childhood and unquestionably follow a leader disturbed him. "It was like a kind of scratchy feeling that wouldn't go away and bothered me more and more."

At the age of 12, in a stance against conformism, Eisenlohr decided to leave the Young Pioneers, the Socialist youth group for East German children. His teachers warned him of the consequences. He would not be able to go to university, and would have to forget about his dream of becoming a veterinarian. But their pressure only made him more determined, he says. As his contact with activists grew, he began to help out at the library and the magazine.

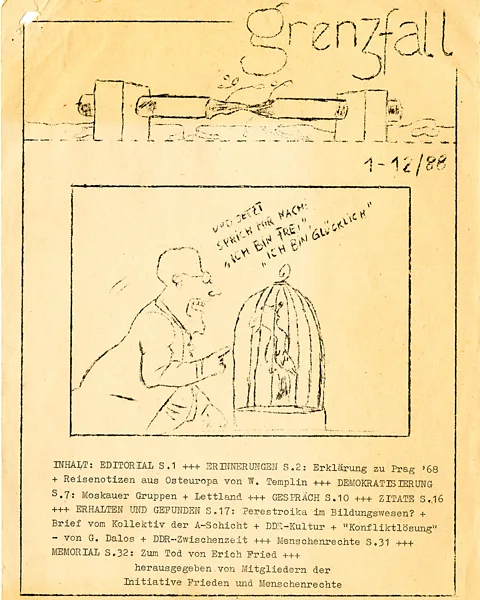

On 24 November 1987, unbeknownst to Eisenlohr, the older members of his group had a secret plan. That night, instead of printing their usual, somewhat legal magazine, they were going to help another group print a much more clandestine publication called Grenzfall, "border case". In the eyes of the Stasi, Grenzfall was "illegal and defamatory". Copies of it were showing up as far afield as Moscow, Prague, Warsaw and Budapest. When the Stasi learned about the plan through an informant, they saw a golden opportunity to arrest the activists in the act of printing it.

But at the last minute, the group abandoned that plan – Eisenlohr was with them, and the activists did not want to endanger a minor. So when the secret police struck, the group were not doing anything illegal. That made no difference to the Stasi, who arrested everyone present anyway, but it was the start of Operation Trap's descent into shambles.

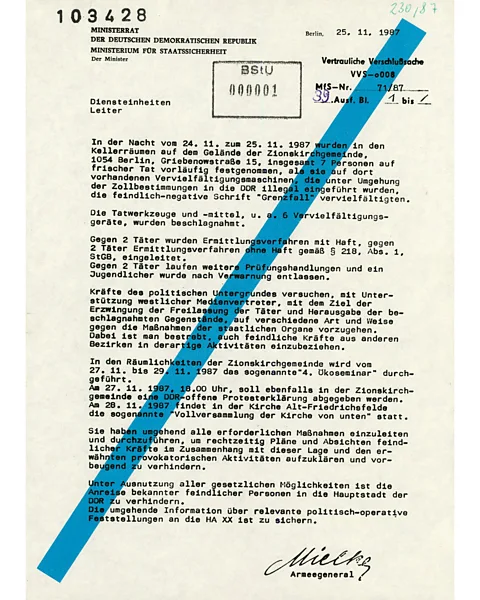

-The-Stasi-Records-Archive

-The-Stasi-Records-Archive"I heard about it first thing in the morning, on West German radio," says Halbrock, who was at a different meeting when the arrests happened. Many others in the East secretly listened to the Western broadcasts. The church, a powerful institution in its own right, was furious. The raid included the supportive pastor's private flat and was seen as a shocking intrusion. West Germany's influential tabloid the BILD-Zeitung ran an article asking "Stasi in the church, peace group arrested: What's going in East Berlin?" A spontaneous solidarity protest sprung up in East Berlin. The Stasi's feared chief himself, Erich Mielke, weighed in and urged his staff to crack down on the sympathisers.

Halbrock, standing in the bitter cold and protesting against his friends' arrest, couldn't believe what he was seeing. "We had teenagers showing up [at the solidarity protest], and elderly people, and someone from a bakery even brought us rolls," he recalls. "In East Germany, that kind of public support was so unusual. More often, people would tell us, 'Are you crazy, risking jail for such nonsense?' But that time, we managed to break through that sense of isolation."

The Stasi Records Archive, BStU, MfS, HA XX, Fo, Nr. 59, 4-14

The Stasi Records Archive, BStU, MfS, HA XX, Fo, Nr. 59, 4-14Even the US became involved: a US Congress resolution expressed concern over the arrests. The timing was critical, too. In December 1987, shortly after Operation Trap, US President Ronald Reagan and the Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, met for a crucial summit in Washington. Earlier that year, Reagan had famously challenged Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall.

Faced with the mess of Operation Trap – arresting people who were doing nothing illegal, failing to stop the protests that followed, angering the church, accidentally arresting a child, having no evidence of criminal activity, and having foreign journalists report it all to the world at a time when the GDR was already increasingly in chaos – the state backed down. Stasi chief Mielke cancelled the detention order for the two activists who were still being confined.

Eisenlohr had already been released on the morning after his arrest and driven back home by the Stasi: "They dropped me at home and said, 'Don't mention this to anyone at school.'"

Alamy

AlamyFor the Stasi, that was far from the end of it. Its people spent months writing reports about the botched mission and the protests, and launched further surveillance operations to deal with the fallout from the raid – all for a mission that, very briefly, netted seven people and a printer.

As Halbrock sums it up: "The raid was a total, embarrassing fiasco for the Stasi." In his view, it exposed the weakness of the entire system. "The GDR's dictatorship was a bit like a nuclear reactor, everything was so tightly controlled and regulated that even a tiny disturbance – like this raid that went wrong – could cause a massive malfunction," he says.

And the library and magazine? "We continued, of course," says Halbrock.

He had already endured many arrests and attempts to intimidate him, been repeatedly beaten up by the police and interrogated by the Stasi. His general strategy was to brush it off. Asked if he had noticed that the Stasi was tampering with his group's coffee kitty to disorient the activists, he shrugs: "They were always doing that kind of thing. Also things like breaking into your flat and taking a bunch of keys, just to let you know they'd been there. I always just ignored it. I was aware that they wanted me to be afraid, and to share that fear with others, and I didn’t want to give them that satisfaction."

The arrests brought the library and its magazine unprecedented publicity.

"For the state, the entire operation totally backfired," says Eisenlohr. "Before, no one in the GDR had any idea who we were. But now lots of people knew about it, because they watched West German TV, or listened to West German radio, and they came to us in droves."

Separately, momentum for change was building due to huge global and societal forces, as Kallenbach points out: reforms in the Soviet Union; the GDR's collapsing economy; masses of people trying to leave; the solidarity movement in Poland; and, ultimately, mass demonstrations where people took to the streets. Then, a press conference about travel reforms triggered a run on the border and the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 Nov 1989.

"The environmental movement was ultimately one piece in the huge mosaic of the peaceful revolution," Kallenbach says.

--Gisela-Kallenbach

--Gisela-KallenbachThe transition period leading up to German reunification on 3 October 1990, and beyond, brought further wins for the environment. More than 4% of the former GDR's territory were turned into nature reserves, including the former death strip along the border. Previously secret environmental data was released. The air and rivers were eventually cleaned up. For Eisenlohr, one major achievement of the movement was simply to dare to fight for change: "It shows the power of the few." (Learn about the 3.5% rule – how a small minority can change the world.)

Kallenbach, Eisenlohr and Halbrock continue supporting environmental and human rights causes to this day. Kallenbach, now 80, has marched with climate activists from Fridays for Future. Eisenlohr visits schools in East Germany to talk about climate change and his experience as a dissident. Halbrock studied history after the fall of the wall, having been prevented from attending university in the GDR. In a neat twist, he then worked at the Stasi archive, where former Stasi victims and researchers can access released files. Halbrock has also written several books about the Stasi and the GDR.

For him, one lasting memory is the bravery of the young people in the 1980s, who were simply fed up with the regime and decided to stand up for their rights. "David Bowie captured that Zeitgeist perfectly with his song from that time, Heroes," says Halbrock. "That feeling of: let's do something. Let's be heroes. Even if it's just for one day."

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.