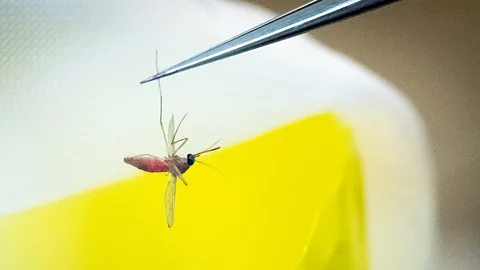

The mosquito-bourne virus that's spreading without a cure

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWest Nile virus is spreading across the US and Europe. This deadly disease has been around for decades, but there is still no vaccine and no cure in humans.

After a distinguished career as one of the world's leading HIV researchers, and then a role as the face of the US government's response to the Covid-19 pandemic, it was a very different virus which recently hospitalised Anthony Fauci.

Last month, the 83-year-old began showing symptoms of fever, chills and fatigue after contracting West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen which was first discovered in Uganda in the 1930s. But Fauci didn't contract the virus in East Africa, instead he was reportedly bitten by an infected mosquito in his back garden in Washington DC, incidents which are becoming progressively more common.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) told the BBC that 2,000 Americans fall ill from West Nile virus every year, leading to 1,200 life-threatening neurological illnesses and over 120 deaths. "Anybody can be at risk," says Kristy Murray, a professor of paediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who has been studying West Nile virus for the best part of two decades. "A simple mosquito bite is all it takes to become infected. And while it's mostly older individuals who we see getting severe disease, young people get it too," she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was late August 1999 when an infectious diseases physician in the New York City borough of Queens reported two cases of viral encephalitis, or brain inflammation, to the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. An urgent investigation commenced after similar cases were identified at neighbouring hospitals. Estimates showed that in total, this mysterious epidemic ultimately infected approximately 8,200 people across the city. It was the first known outbreak of West Nile virus in the western hemisphere.

No one knows exactly how the virus was introduced to the US from parts of Africa, the Middle East, southern Europe and Russia where it had circulated for decades, but research has since shown that birds are the main carriers of the virus. Mosquitoes contract the virus when feeding on infected birds, before passing it onto humans.

Since that initial outbreak in 1999, there have been more than 59,000 US cases and more 2,900 deaths from West Nile virus, although some estimates place the real number of infections as exceeding three million.

Now, there are growing concerns that West Nile outbreaks in the US and around the world will become more frequent due to climate change. Studies have shown that warmer temperatures can accelerate mosquito development, biting rates and viral incubation within a mosquito. In Spain, where the virus is endemic, an unprecedented outbreak in 2020 has been followed by a prolonged period of escalating circulation.

This has led to particular concern because while infections are predominantly asymptomatic, with only one in five people experiencing mild symptoms, severe cases can result in lifelong disability. In around 1 in 150 people, the virus can invade the brain and central nervous system, causing life-threatening inflammation, and in many cases, brain damage.

In particular, people who are immunocompromised in some way, over the age of 60, or have diabetes or hypertension, are particularly vulnerable. "With hypertension, we think that increased pressure in the brain allows the virus to cross the blood brain barrier more readily," says Murray.

Having followed patients suffering from severe cases of West Nile viral infection for many years, Murray says that the resulting inflammation can ultimately cause such severe brain atrophy or shrinkage that scans often show similar patterns of damage to people who have suffered traumatic brain injuries.

"For those with severe disease, about 10% will die from the acute infection and around 70-80% will experience long-term neurological consequences," says Murray. "For those who survive, it doesn't necessarily get better, it often gets worse. People report depression, personality change, things like that," she says.

Yet despite these inherent risks, there is currently no vaccine or even any dedicated treatment which can help people suffering from the infection. "It's really become a neglected disease," says Murray. "This year alone, I've gotten contacted so many times by patients who are newly diagnosed with West Nile, asking, 'What can we do?' And I'm like, 'There really isn't anything'. It's just supportive care and it breaks my heart to have to tell them that," she says.

When it comes to the lack of preventative measures against West Nile infections, perhaps one of the biggest ironies is that safe and highly effective vaccines have been available for horses for the past 20 years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBetween 2004 and 2016, there were nine clinical trials of different human vaccine candidates, two launched by the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi and the remainder funded by either biotech companies, academic institutions or various US governmental organisations. Yet despite all being generally well-tolerated and inducing an immune response, none of these trials made it to a Phase 3 clinical trial. This is the final and most crucial hurdle before a vaccine can be authorised, and involves testing if a treatment is effective. The last of these trials, sponsored by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, did not progress any further than Phase 1 – the first step, which usually aims to discern if the intervention is safe.

Carolyn Gould, a medical officer with CDC's Division of Vector-Borne Diseases in Fort Collins, Colorado, says that the sporadic and unpredictable nature of West Nile outbreaks has been a big hurdle, as the virus needs to be circulating at that particular time to be able to prove that a vaccine is actually working.

"Some trials launched during a lull without many cases," says Murray. "But then there was an outbreak in 2012 where we had over 2,000 cases in Texas alone, and over 800 of them were severe cases. So if they'd waited a few years, they could have had all the participants they needed," she says.

In 2006, a major study of vaccine cost-effectiveness concluded that a universal West Nile virus vaccine programme would be unlikely to save the healthcare system money. Gould believes that the sheer cost of developing a vaccine, combined with uncertain benefits or financial returns from a pharmaceutical company's perspective, has been a major deterrent.

However, a number of possible alternatives have been offered in recent years. Some scientists have recommended a dedicated vaccine programme for over 60s who are at greater risk from the virus, while Gould proposes a programme aimed at specific regions in the US where virus-carrying mosquitos are most prevalent. In addition, Gould believes that the increasing evidence surrounding the longer-term consequences of West Nile virus-induced neurological damage could make funding vaccine development more appealing. More recent estimates have suggested that the economic burden of hospitalised West Nile virus patients is $56 million (£42 million), and the short and long-term costs can exceed $700,000 (£530,000) per patient.

"More recent studies show it could be cost-effective if deployed to high-risk groups in specific geographical locations," says Gould. "From a manufacturer's standpoint, it would be important to consider the high numbers of people at increased risk for West Nile virus disease with serious consequences, when conducting a sales forecast," she says.

Given the ongoing fatalities and neurological disabilities caused by the virus, Paul Tambyah, president of the International Society for Infectious Diseases, describes the current inability to find a solution as being down to "a lack of imagination".

"Everybody's thinking you've got to do this massive phase 3 trial in the US, which is difficult for a disease which only appears for two and a half months in the year, which is also unpredictable as some years you have a massive outbreak, and other years you don't," says Tambyah.

Instead Tambyah proposes a large international trial with hundreds of different trial sites, not just the US but in parts of Africa where the virus is endemic, as a more effective way of gathering the evidence required. While it would require several million dollars of funding to launch such an initiative, he says that it could be possible with the help of public-private partnerships, pooling together the resources of various governments of affected countries and small and medium sized pharma companies to help mitigate the financial risk involved, in case the trial failed to prove efficacy.

"There are a few possible mechanisms out there to make this happen," he says. "It just requires the willpower to do something about it."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJust as pressing is the need to find more effective treatments for people who do experience serious disease as a consequence of West Nile viral infection. Murray says that while a couple of drug candidates were developed based on artificially generated antibodies against the virus called monoclonal antibodies, they did not progress further than rodent studies, with developers facing the same tricky hurdles as vaccine manufacturers when it came to devising a suitable clinical trial.

Murray feels that the most urgent need is for a drug which not only clears the virus but can be used to dampen down the raging inflammation within the brain which causes many of the neurological complications. She suspects that in some cases the virus sets up camp within the brain's nerve cells where it is not easy to attack.

"It crosses the blood-brain barrier and sets up within the brain, and that's where you get the inflammation and damage,” she says. "The problem is that a lot of our existing antivirals can't reach the brain so it can't get to that space where they need to be effective."

But there may be alternative possibilities. Tambyah feels that we can take many lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic, where despite the global arms race to develop an antiviral against the Sars-CoV-2 virus, one of the most effective treatments turned out to be a cheap steroid called dexamethasone. Its efficacy was identified by the Recovery trial in the UK, which examined a variety of possible treatments.

Having treated numerous patients with brain inflammation as part of his role as a senior infectious diseases consultant at the National University Hospital in Singapore, Tambyah is convinced that finding the right steroid for reducing the inflammation can ultimately help many patients to eventually recover. "West Nile virus is a flavivirus and there's no licensed antiviral at the moment for any of the flaviviruses – dengue, Zika or Japanese encephalitis," he says. "I think steroids are probably going to be the future."

More like this:

• Why some people are volunteering to be infected with diseases

Ultimately though, more data is needed to identify the most appropriate drug for tackling West Nile virus, and Tambyah suggests that this could be done through a similar study to the Recovery trial.

"We could potentially recruit patients with encephalitis from West Nile virus and include various interventions, some steroids, monoclonal antibodies as well, and hopefully that would yield an answer," says Tambyah. "If there was the will to do something about it, sufficient funding from the governments of affected countries, it could happen," he says.

Ultimately Murray and Tambyah are hoping that the spotlight which has fallen on West Nile virus as a result of Fauci’s illness will help convince policymakers to devote more funding towards this much neglected disease.

"This virus is here to stay and we're going to keep having these outbreaks," says Murray. "If someone like Fauci, who's in a position where people listen and respect him, can speak about this, that might help give a push for additional funding to study the virus and allow scientists to focus on vaccines and therapeutics. Because it's 25 years now since West Nile emerged in the United States and we still don't have anything."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.