'I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy': The people who work inside the eye of a hurricane

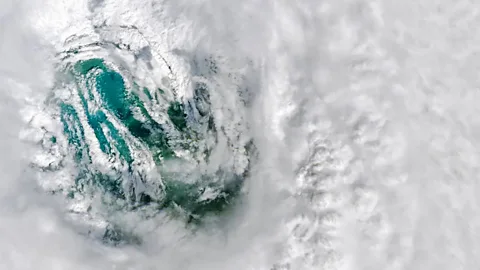

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe centre of a hurricane is the focus of its power. But for scientists and early-responders, it can also offer life-saving opportunities.

It may seem calm, but the eye of a hurricane is essentially an enormous trap. Inside this arena of relative rest, ferocious winds fall away, thunderclouds are replaced by sunny blue skies, and pounding rain is swapped for spring-like warmth – but only until the opposing edge of the eye wall passes overhead.

Birds caught inside often have little chance of escape, forced to fly with the moving storm until they are exhausted. For the eye cannot be entered or exited without passing through a band of deep convective clouds that rise to a height of 15,000 metres (49,000ft). This is the strongest and most dangerous part of a hurricane – its eye wall. On the ground, eye-wall wind gusts can reach over 330 km/h (200 mph) – capable of uprooting people, cars and homes.

"Personally, it was something I'd never want to experience again: I wouldn't wish it on my worst enemy," says William Hamilton, now a climate change adviser to the Bahamas Ministry of Health, as he recalls the time Hurricane Dorian ripped through the Bahamas in 2019.

Hurricane Milton

Barely two weeks after major Hurricane Helene inundated the US, another major hurricane is poised to make landfall.

Hurricane Milton intensified "explosively", fuelled by warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico, reaching category five strength on 7 October before weakening to a category four. The storm is due to make landfall along the west-central coast of Florida late Wednesday or early Thursday morning, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Yet there are reasons why some head towards the core of a hurricane's deadly vortex and not away. From scientists in the air, to storm-chasers and rescue services on the ground, the centre of a storm has a pull that is both fearsome and, potentially, life-saving.

Plus, as climate change makes hurricane systems more dangerous, this need to understand their inner workings is greater than ever. So who are those who head towards these hurtling weather phenomena, and how can their experiences help?

The hurricane hunters

In the inland US state of Wisconsin, a young Heather Holbach had first-hand experience of how "terrifying" a tornado could be. Eager to learn more about their threat, she started watching The Weather Channel – and ended up becoming hooked by hurricanes instead.

"I found it really fascinating there was such a thing," she says of the airborne flight-crews known as "hurricane hunters" who collect scientific data from inside these giant storms. "My dad was a pilot and I'm a big roller-coaster enthusiast, and I thought flying into one sounded really exciting – so I set that as my goal."

Lt. Cmdr. Kevin Doremus NOAA Corps

Lt. Cmdr. Kevin Doremus NOAA CorpsAfter university, Holbach joined the Hurricane Research Division at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (Noaa's) Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Since 2013, she has flown through more than 13 different hurricanes, including numerous category 4s and 5s – the highest ratings a storm can reach.

The resulting emotions can be intense. On flying up into Hurricane Irma in 2017, Holbach wasn't sure that anything she was leaving on the ground in her new hometown of Miami would be left standing when she returned. "It was a strange mix of emotions," she recalls. "There's always a fascination with the storm, but also, that time, a lot of nerves on behalf of my apartment, my friends and my neighbours."

Nor is the job of a hurricane hunter risk-free.

Jason Dunion, a meteorologist at Noaa's Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, has flown in "40 to 50 different storms" over his career and vividly recalls his experience of Hurricane Dorian in 2019. The most powerful hurricane ever to hit the Bahamas Islands, Dorian's rapid intensification during the course of their flight-time was "mind-boggling", he says.

"I don't think I'd ever appreciated the power of mother nature to that level before."

So precautions are necessary Dunion warns, such as flying no lower than 8,000 to 10,000 feet (2,400 to 3,000m). Sudden downdrafts of over 50mph (80km/h) can leave crew members "floating if you didn't have your seat-belt on".

This was something the crew of WP-3D Orion – nicknamed "Miss Piggy" – experienced as they flew into the category five Hurricane Milton on 8 October 2024 as it moved across the Gulf of Mexico towards the Florida coastline. The winds at the eyewall of a storm can be so turbulent that they can hurl an aircraft around so that those onboard experience strong g-forces.

Eyeing up the storm

Despite the risks, hurricane hunter crews keep on returning to the eye of the storm – since the data they send back to the National Hurricane Center (NHC) is invaluable to forecasters around the world.

Various technologies help this process. Radar transmitters, for example, send out electromagnetic pulses that reflect off precipitation within a storm and help document how much rain is falling (larger droplets and hailstones scatter more radiation than raindrops).

Stepped-frequency microwave radiometers (SFMR), attached to the wing of the aircraft, measure the microwave radiation emitted by seafoam and whitewater at the ocean surface and uses it to determine wind speed. Meanwhile, drones, launched from the planes, can fly low above the waves – monitoring how energy is being transferred from the sea upwards to fuel the storm. These can even be left to "loiter" in the storm's eye, allowing continued monitoring of pressure changes while the aircraft continues its mission.

These and other tools allow a hurricane's pressure, wind speed, temperature and humidity to be tracked to greater levels of accuracy than satellite observation alone achieves, says Dunion. "Forecasters are always using satellites, but they're always also on the edge of their seat waiting for plane data to get in."

The data additionally informs "research into what makes a hurricane tick", Dunion says – or the opposite, such as how dust from the Sahara Desert can inhibit their growth.

And throughout all this, the eye and eye wall remain crucial – since by making multiple passes through the eye, on missions known as "fixes", the crews are able to gather an overall view of the storm.

Observations from within the inner core of a hurricane are also one of the keys to forecasting rapid changes in storm strength. Predicting such shifts in intensity involves observing inner core cloud properties, including air motion, within the storm, says Ting-Yu Cha, a postdoctoral fellow in atmospheric science at the National Science Foundation's National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Meanwhile, perhaps among the strangest features a hurricane sometimes shows is the formation of a second eye wall, with a new outer ring of thunderstorms emerging around the first.

Satellite and aircraft data are the only ways forecasters can detect whether this phenomena has occurred over the open ocean, adds Alvin Cheung, a graduate student at the University of Maryland's department of atmospheric and oceanic science. Such a formation can temporarily pause intensification, but is then sometimes followed by a renewed storm intensity as the storm's wind field enlarges.

Real-time monitoring from within the storm can thus help save lives, says Ting-Yu, allowing people to make evacuation decisions "well before the storm hits".

Area I, Noaa

Area I, NoaaOnce a hurricane makes landfall, it's over to those on the ground to continue the chase through the eye of the storm.

Michael Biggerstaff, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Oklahoma, has deployed Shared Mobile Atmospheric Research and Teaching (SMART) radar systems into 14 hurricanes since 2001. This involves driving out two to three days ahead of the storm and setting up the radars before landfall. Then operating them throughout the storm from inside the radar truck. "It's like being on a wooden rollercoaster for 20-plus hours," Biggerstaff says.

But the wait can provide vital insights. Such as how mesovortices (where the strongest gusts of winds are typically found) along the inner edge of the eye wall change the strength of the vortex circulation after the landfall – potentially producing extreme damage.

Chasing the storm

Storm chasers, too, argue that they can provide valuable data from inside landfalling hurricanes.

"We typically deploy probes to measure conditions within the strongest part of a storm," says Edgar Oneal, who has been storm-chasing for 11 years and recently joined Team Dominator, a storm chasing group run by meteorologist Reed Timmer.

Oneal's focus is currently on participating in Reed's scientific research on tornadoes, which is attempting to capture their 3D structure from inside. He also runs their live-streams, including of hurricanes. He says that social media live-streams can provide valuable updates to locals who did not evacuate.

There is, too, a certain curiosity that draws him towards hurricane eye walls, Oneal says. "[Yet] while there can be an element of excitement, it's crucial to keep it in check: these hurricanes devastate lives."

Rather than just "adrenaline junkies seeking internet fame", as some people may perceive them, Oneal argues storm chasers make important contributions to science and media. He also says he's helped rescue more than 20 families during his time chasing. And has never required rescue himself, even bringing his own fuel to avoid consuming the local resources.

The risks, however, are numerous: from getting injured by high winds and debris, to drowning or being cut off by floodwaters.

Connor McCrorey

Connor McCroreyRyan Cartee likewise emphasises the importance of staying safe during his dangerous work. Among other roles, Cartee is a storm tracker for a local news outlet, a photojournalist and a first-responder, and has been chasing hurricanes for 20 years. In Hurricane Katrina in 2005, he witnessed a storm surge of up to almost 30ft (9.1m) that gutted homes and businesses.

One way those documenting hurricanes mitigate this risk, he says, is to travel to predicted hurricane-landfall locations ahead of time in order to find a relatively safe position. "To position for eye intercept; you have got to have some sort of cover if it's a larger system," he adds, "due to greater winds throwing pieces of debris around to the storm surge."

But the best protection from a hurricane is to evacuate when advised to do so, Cartee says.

Emergency relief

But for those who don't or can't leave, the passing of the storm's eye can be a crucial opportunity to seek shelter.

When Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas in 2019, William Hamilton was stationed as a medic at Marsh Harbour's health care centre. Living in staff quarters across the way from the clinic building, he and his wife quickly became trapped inside their home as the storm gathered strength.

"We lost all communication: electricity went off, cell phone towers were down. So we had no idea where the storm was at the time; we just knew that it was so intense that tiles fell from the roof and water started to pour into the flat."

"You could see cars were overturned outside, all of the lampposts collapsed – and we assumed this was the passing of the front eye wall."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThen, all of a sudden, the winds calmed enough for their neighbour to come out of her flat and advise that the eye was passing over, and that they should move to the safety of the nearby clinic.

If they hadn't made it out of their home during this respite, Hamilton believes their ability to recover from the storm's traumatic impact would have been even harder. "We may have been alive, but the mental anxiety and anguish of being [trapped in the house] for so long would have been even more distressing."

Once at the clinic, William and his wife were able to attend to others who were also using the storm's eye as an opportunity to reach safety and medical attention. Hamilton began work within 20 minutes of getting to the clinic on 1 September – and continued with little let-up until the first US Coast Guard helicopter providing relief arrived on 3 September.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHamilton's experience of Dorian led to the onset of PTSD, and he required medical support in the aftermath. "I tell patients it's easy for me to fix a broken leg, but it's difficult to hear people say, 'My mother is dead, I left her in the closet.' I heard stories of loss so many times during those 48 hours and that was gut-wrenching."

Hamilton saw similar experiences of trauma among his patients, and has since argued that hurricane response strategies should include mental health professionals.

The direct passing of a hurricane's eye may therefore offer a rare and brief opportunity to protect life, but it cannot shield from a hurricane's devastation.

According to James Shultz, associate professor of public health at the University of Miami, "if we put too much emphasis on the eye and eye wall, we risk ignoring the broader impact of the rest of the storm", as well as the opportunities for mitigating disaster – from fortifying hospitals to revising buildings codes.

Meanwhile, for those who have survived the passing of a hurricane's core, the experience is not one they will likely take lightly ever again, says Hamilton. And as climate change causes hurricanes to grow stronger, with the most socioeconomically disadvantaged also often the most vulnerable, the need for better preparation and understanding among the wider population is greater than ever.

"We need to make people aware we all have a role to play – as the storm profiles are growing stronger," says Hamilton. That involves everything from efforts to reduce global emissions, to introducing better swimming programmes in low lying regions, he suggests. "Everyone should be in one to at least be able to survive."

--

This article was originally published on 12 September 2024. It was updated on 9 October 2024 with details of Hurricane Milton.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.