Why we need a better way to measure hurricanes

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHurricanes are ranked by wind speed, which leaves out the cause of 90% of deaths during extreme storms. Scientists are racing to update the imperfect system we rely on to warn just how deadly a storm will be.

Rapidly intensifying to a category five hurricane before dropping to a category four, Hurricane Milton is due to make landfall in Florida on Wednesday. Hurricane Milton is set to bring potentially catastrophic storm surge along the coast, just two weeks after Hurricane Helene. One meteorologist became emotional describing the strength of the storm and the risks it will bring so soon after the last major hurricane.

Hurricanes are often highly dangerous in ways not always captured by the traditional ranking system. Earlier in the 2024 hurricane season, Hurricane Ernesto caused devastating damage in Puerto Rico. The storm received the lowest ranking – category one – on the official hurricane categorisation, the Saffir-Simpson scale, due to its wind speeds of 75mph (120km/h). But storms that just clip in at the lower end of the hurricane scale can sometimes cause as much damage as a category five. (Read about why we underestimate category one hurricanes.)

As climate change brings stronger storms and more extreme hurricane seasons, there's a growing call to rethink the way we rank hurricanes. The Saffir-Simpson scale, though widely known and used for more than 50 years, has major flaws that make scientists question whether it is the best measure for the job.

There are several emerging contenders that aim to improve on the Saffir-Simpson scale, and ultimately help save lives through better warning systems.

The water problem

Created in the early 1970s by Herbert Saffir, a US civil engineer, and later added to by Robert Simpson, a meteorologist, the scale measures a storm's maximum sustained wind speed.

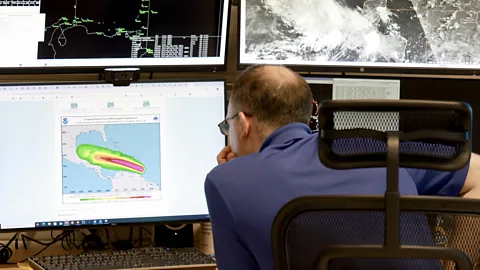

This is used to rank hurricanes from one to five, with five being the most intense. The wind speed is measured by reconnaissance aircraft flown by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), which drop instruments that measure the pressure, wind direction and speed as they fall towards the sea.

The Saffir-Simpson scale does not take other hurricane impacts into account, such as storm surge, heavy rainfall or flooding.

However, the greatest threat to life a hurricane brings comes from water, not wind. In fact, 90% of all hurricane-related deaths worldwide are caused by drowning, either in storm surges or flooding caused by extreme rainfall, according to the Florida Climate Center at Florida State University.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The Saffir-Simpson scale is inadequate," says Michael Wehner, a senior scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California who specialises in the changing behaviour of extreme weather events. "The issue is that the scale is simply a measurement of the highest wind speed at any point in the storm. However, most of the damages are from water, not wind."

Some of the costliest hurricanes on record, Hurricane Sandy for example, have been category one storms with relatively low wind speeds. Yet these storms sometimes cause severe coastal flooding. Sandy's floodwaters exceeded the 100-year floodplain boundaries by 53%, damaged hundreds of thousands of homes and led to damage estimated at $88.5bn (£68.2bn).

"Maximum wind speed has very little to do with storm surge," says Vasu Misra, professor of meteorology at the Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies at Florida State University. "Storm surge is proportional to wind stress," he says. Stress is the force the winds exert on the ocean surface, he explains.

"So it's really about the horizontal distribution of winds around the tropical cyclone, rather than a point estimate," he says.

Storm size

The Saffir-Simpson scale doesn't factor in either the overall size of a hurricane or the horizontal distribution of the winds, he adds.

Misra has proposed a new metric to measure the destructive power of hurricanes, to complement the Saffir-Simpson scale. Known as the Track Integrated Kinetic Energy, or Tike, the metric measures the size of the wind field, along with the intensity and lifespan of the storm. Instead of using reconnaissance aircraft, this methodology would rely on satellite estimates of the wind distribution of hurricanes, Misra says.

But there are several challenges which could make it difficult to get accurate data, Misra says. There is often heavy cloud cover around the hurricane, which means there will be "some uncertainty", he says.

Another "big practical problem" is that these estimates are only available for the Eastern Pacific basin and the Atlantic Ocean, not for the Indian Ocean or West Pacific Ocean, due to the location of the satellites, he adds.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNew technologies, such as saildrones, wind-propelled vehicles that look like small sailboats and measure the intensity of hurricanes, are helping improve hurricane data, says Misra. "But cost is going to become a problem," he says. "How many saildrones can you really launch to [capture] the distribution of the winds around a hurricane which can span thousands of kilometres?"

Kerry Emanuel, professor emeritus in atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), says the entire methodology needs a complete rethink.

"I'm in favour of ditching the Saffir-Simpson scale and starting afresh," says Emanuel. "It is not a very good measure of the actual risk. The focus has been on meteorology rather than risk and we need to change gears.

However, the Tike metric may also come up against similar problems as the Saffir-Simpson, says Emanuel. "Any scale that only deals with wind is going to fail on many occasions and that's why we need to replace it," he says.

"No one scale can represent all these impacts for every location," Jamie Rhome, deputy director for Noaa's National Hurricane Center (NHC), tells the BBC. To alert people to the risks of storm surges during hurricanes, the NHC has set up a storm surge watch and warning system, he says.

As hurricanes are "multi-hazard phenomena, the National Hurricane Center prefers to communicate the potential impacts of these hazards separately, since they can occur at different times and places," Rhome says.

Traffic lights

Emanuel would like to see a new classification system which is "very similar to something that's used by the UK Met Office, which simply rates the magnitude of the risk on a colour scale and [issues] a yellow, amber or red alert", says Emanuel.

The Met Office's weather warnings are given a colour depending on both the impacts the weather event may have and how likely those impacts are to occur.

"We need to move towards a human-centred, rather than a storm-centred framework for hurricane warnings," says Emanuel.

A more personalised approach, which provides people with the probability of a range of severe weather events occurring in their area, would help people understand their risk level and take the necessary precautions, he says.

"We need a separate smartphone app that is risk-focused and knows where you are, so that it can tell you what's the probability that there will be destructive winds in your community or that water levels will flood your house" he says. "We already do that for ordinary weather forecasts."

Emanuel notes there is a feeling among scientists that "the public isn't sophisticated enough or intelligent enough to interpret this", he says, adding he does not share this view.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe simplicity of the Saffir-Simpson scale, however, does make easy for the public to understand. "It's easy to communicate the threat of the tropical cyclone based on these categories and that is probably the primary reason for the reluctance in changing this metric to anything else," says Misra.

Wehner says it is important that the public understands that "the Saffir-Simpson scale is not the whole story".

"I think the public benefits from more detailed information. The National Hurricane Center provides this and good broadcast meteorologists use this effectively," he says.

Category six hurricanes?

Hurricanes are becoming more intense and destructive as ocean temperatures rise, providing more fuel for storms. (Read more about how modern hurricanes are rewriting the rules of extreme storms).

According to a 2020 study, storms today are 25% more likely than they were 40 years ago to reach the 111mph (180km/h) threshold for a major hurricane (category three and above).

With more intense hurricanes, with faster wind speeds, would it help to add a category six to the existing Saffir-Simpson scale?

In February 2024, Wehner and his colleague James Kossin, a climate and atmospheric scientist retired from Noaa, published a paper on the shortcomings of a Saffir-Simpson scale that stops at category five. "There's no reason for [the scale] to be capped anymore," Kossin told the BBC during Hurricane Beryl earlier in 2024. There are hurricanes that have already surpassed the theoretical threshold for a category six, such as Hurricane Patricia in 2015, and Typhoon Haiyan in 2013.

But simply adding a category six to describe stronger storms may do more harm than good, Kossin says. "In fact, I think that's a terrible idea, for a lot of reasons," he says. For instance, a higher category could make people dismiss category fives as not so dangerous, he cautions. "That's just human behaviour," he says. "Some people will look for any excuse not to evacuate."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWehner says Noaa's National Hurricane Center should ultimately decide whether to add a category six to the current scale.

The NHC's Rhome says that category five already describes "catastrophic damage" from wind. "So it's not clear that there would be a need for another category even if storms were to get stronger," he says. As most hurricane-related fatalities are caused by water, rather than wind, "we don't want to overemphasise the wind hazard by placing too much emphasis on the category".

It's a view Wehner shares. "The hazards from a hurricane are more complex than a single number can convey," he says.

Some scientists, however, do see merit in adding a category six. Emanuel says if we are going to stick with the Saffir-Simpson scale, expanding it to a category six would send a "clear message to people that climate change is influencing hurricanes. Its primary utility would be to draw attention to that fact".

But others share concerns about the classification. "Anything above category three should be considered threatening," says Misra. "People should not be waiting for a category six to act or react."

Heather Holbach, a research assistant with the hurricane research division at Noaa, also worries that increasing the number of categories could impact how seriously people take storms with lower rankings, and sees no reason for a category six for scientific reasons.

"One of my concerns would be: is that going to make somebody think even less of a category one or category two, which are still significant threats?" she says. "I think there's a huge social science component that needs to be understood a lot more."

--

This article was originally published on 22 August 2024, and was updated on 8 October 2024 with details of Hurricane Milton.

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.