The extinct Olympic sport that was the 'dullest' of all time

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonIn the plunge for distance, any form of exertion was strictly forbidden.

William Dickey teeters on the edge of the diving block, contemplating the placid waters of the lake below. He's a future swimming champion – an elite sportsperson and member of the New York Athletic Club. Only, he doesn't quite fit the mould.

Clad in a baggy one-piece bathing suit made from wool, and sporting a bushy chevron moustache, there's not a bulging muscle or V-shaped torso in sight. The competitor takes a deep breath into his well-padded frame, and gently tips himself, arms outstretched, into the water below.

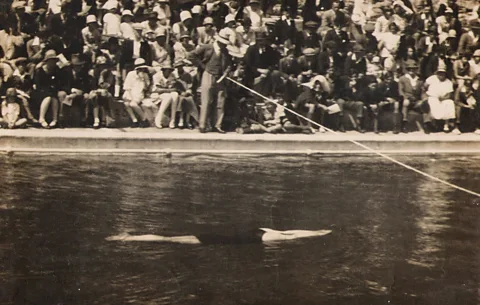

It's a muggy September day at Forest Park in St Louis, Missouri and Dickey is competing in the 1904 Olympics. A few seconds later, he floats to the surface of the lake. He's lying face-down, perfectly still, and gently drifting – his body frozen into a long stretch. This is impressive – the race is going well. He wafts along like a log caught in a light breeze, at around the speed of a sleeping duck. Could he… yes, he's going to win. Might he even break the record?

Alamy

AlamyThis is the "plunge for distance", a race that was once a staple of any swimming competition – as conventional as the 50m (164ft) freestyle or 100m (328ft) backstroke. Then it silently disappeared from the sporting calendar across the globe. Now even professional swimmers have never heard of it.

The distance plunge, as it was also known, defied the usual conventions of athletics. It didn't require superhuman strength, endurance, agility, speed, or even creative flair – in fact, apart from an initial dive, any form of exertion was strictly prohibited. But most of all, it was also, according to many contemporaries, eye-glazingly dull to watch, and holds the dubious distinction of having been labelled the lamest, weirdest and most boring Olympic sport of all time. But was it really that easy? And does it deserve its wearisome reputation?

A floating body

The rules of the plunge for distance were as particular as those for any sport. The competitor began with a regular standing dive, of the kind you might attempt into the hotel swimming pool on holiday – casual, and not particularly ambitious. This was the "plunge", and it was done from a height of 18 inches (46cm), without a diving board.

Once the competitor had hit the water, they had to keep their body perfectly still – they could not move a muscle or propel themselves in any way. There were two ways of assessing performance: the winner was either the person who travelled the furthest before they were forced to raise their face to breathe, or the competitor who achieved the longest distance within one minute.

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonAfter a slow glide underwater, the plunger inevitably bobbed up to the surface, where they would continue to float passively, arms outstretched, hoping to rack up a few more inches. As they wafted along, there was so little action, athletes could have been mistaken for having abruptly fallen asleep. As a result, the event has been derided as "competitive floating".

In 1930, the sportswriter John Kieran laid out his view in the New York Times: "The stylish-stout chaps who go in for this strenuous event merely throw themselves heavily in the water and float along like icebergs in the ship lanes."

Even the British journalist Archibald Sinclair, who was sympathetic to distance plunging, stated matter-of-factly that the activity was often vetoed from swimming competitions because it didn't produce any excitement among spectators. In all, "to the uninitiated the contests appear [an] absolute waste of time," he wrote in the book Swimming, published in 1893.

An unconventional athlete

With its relaxed approach to physical effort, distance plunging attracted an unlikely cast of champions that may otherwise not have become involved with competitive sport. They tended to be indifferent swimmers, and the vast majority had more body fat than the average sportsperson today.

Take Frank Parrington, who set the current world record of 86ft and 8in (26.4m). When he wasn't cruising through water very slowly, winning the Amateur Swimming Association plunging championship 11 times, he worked as a police sergeant in Liverpool. Dave Parrington, head diving coach at the University of Tennessee, is his grandson. He explains that Frank Parrington got into distance plunging between serving in World War One and World War Two. He was a "big man with a big chest and a bit of a belly", and was probably introduced to the sport at the local swimming baths, says Dave Parrington, who suggests that this physique may have nudged him in the direction of this particular event.

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonUnlike in many other sports, possessing enough fat – and not too much muscle – was thought to be vital to the success of distance plungers. Slender athletes were written off as plungers, and rarely did well. In 1916, one champion swimmer went so far as to claim that the plunge for distance records were all held by "men of weight", according to his analysis.

Fat is less dense than water, and can therefore provide competitors with added buoyancy, while muscle and bone are more dense, increasing the risk of a person sinking. Dave Parrington explains that lean, muscular people won't necessarily end up at the bottom of the swimming pool, though some bodybuilders have this problem. Instead, when they rise up to the surface for the second half of their plunge, their legs might drop. "So all of a sudden they're no longer flat, their legs… they'll actually be bent below the water line," he says. With their lower half dangling, a person's chances of a successful distance plunge are slim – above all, this is a sport of hydrodynamics.

A matter of skill

Even in its heyday, distance plunging was widely disparaged as a non-event that apparently required no skill or talent whatsoever. In the years before World War One, athletic unions and college authorities in the US were urged to drop the sport, which became something of a joke.

In August 1920, a group of youths improvised the "West Side Baths" on West 48th Street in New York City – a playful summer setup involving a fire hydrant and fire hose operated by a fireman, who sprayed water across the road to create a kind of urban river. According to a contemporary report in the New York Times, among the delirious fun to be had there was the satirical game "plunge for distance", which involved a running bellyflop onto the street's slippery asphalt, leading to a 15-20ft (4.6-6m) slide. The journalist noted "It takes more skill and a deal more hardihood than the plunge for distance in a swimming tank."

But distance plunging was not just down to adipose tissue – and advocates of the sport believe its reputation was wildly off the mark.

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonIn the absence of a professional coach, Frank Parrington used to take his young son to the swimming pool and ask for observations on his technique. Dave Parrington never met his grandfather, who was killed at just 42 years old during a series of devastating bomb raids on Merseyside during the spring of 1941. Nevertheless, his methods have been passed down the generations.

Firstly, it's important to get the angle of entry to the water right, explains Dave Parrington. If you dive too shallow, you'll surface too soon – too deep, and you'll bob up abruptly. Frank Parrington was a master of this, he says, and also paid particular attention to his floating posture. "One of the things that my dad told me was that his father would ask him to make sure that once he had surfaced, his heels were touching the surface of the water, not hanging below it," he says. This streamlined position allowed him to glide further, since the body must be kept perfectly still.

Finally, Frank Parrington taught himself to control his breathing. Many people exhale when they dive, says Dave Parrington, but "you want to make sure that when you enter the water you have air in your lungs to help maintain that buoyancy," he says.

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonIn addition to the factors distance plungers could control themselves, the event came with one major hidden challenge – currents. Many competitions, including the 1904 Olympics, were held outdoors. And if the water and wind weren't perfectly still, athletes could encounter resistance that hindered their gliding efforts. Even at indoor contests, if the person who was in the pool just before them swam back towards the starting line before getting out, they could inadvertently create a similar effect.

Dave Parrington often practises distance plunging with his diving students, just for fun, and this has reinforced his own appreciation of his grandfather's skill. "None of them even come close," he says. Though Dave Parrington was once a competitive diver himself and participated in the 1980 Olympics, the furthest he has managed to plunge is 75ft (23m).

An inevitable demise?

Alas, the subtle finessing involved in a distance plunge was largely invisible to the average spectator – and the sport's reputation as formidably soporific never wore off.

As early as 1908, just four years after its Olympic debut, the distance plunge had already been removed from the programme forever.

Martin Polley, a professor in the department of history at De Montfort University, UK, explains that the Olympics were particularly experimental in the early 20th Century. Events included a water-based obstacle race, in which contestants had to swim under and clamber over rows of boats, underwater swimming – canned because spectators couldn't see anything that was happening – tug-of-war and croquet.

After the Olympic rejection for the distance plunge, things were about to get worse. "It had been criticised in the press as early as the 1890s, in both the UK and the USA," says Polley, who explains that by the 1930s, the sport was being phased out of national competitions. But even in the 1980s it still hadn't completely vanished – he remembers competing in distance plunging competitions at secondary school in the UK.

The trickiest part, Polley says, was to keep your arms outstretched in the dive position once you had entered the water. "It’s counter-intuitive to be in a swimming event and not to move!" He also found it hard to contain his momentum to a straight line because the body tends to drift.

Dave Parrington

Dave ParringtonWhile he enjoyed competing – he remembers being pleased at having the pool entirely to himself when it was his turn – Polley confirms that watching the sport was indeed "pretty boring". "There was not much crowd noise, as the competitor can't really hear anything when they are underwater, but there were big cheers when people who had gone a long-distance surfaced," he says. He never won any of these events himself, but he was probably mid-ranked, he says.

Today distance plunging is almost completely extinct, apart from the occasional resurrection at school swimming galas. But should the world heave a collective sigh of relief, or could we be missing out on the thrill of watching people float very, very slowly?

Medal Moments

Want to read more about the Olympics? Sign up for Medal Moments, your free global guide to Paris 2024, delivered daily to your inbox throughout the Games.

For a sport that was widely scorned, just occasionally, the plunge for distance received rapturous reviews. At one event hosted by the YMCA youth organisation in Victoria, British Columbia, it was described as "certainly the most interesting event of the evening", after a swimmer eventually cruised almost the entire length of the swimming pool.

In response to the threat of the sport's banishment from certain competitions, one former champion remembered in 1917: "At many a meet I've seen the crowd watch breathlessly a close fight for laurels between evenly matched contestants, then break into a storm of applause at an especially good performance."

Alamy

AlamyDave Parrington explains that the plunge was particularly popular at exhibitions and the openings of new public baths, where plungers often disregarded the 60-second time limit and racked up impressive distances – all while holding their breath for several minutes. In these circumstances, his grandfather could travel some 110ft (34m).

Back at the 1904 Olympics, Dickey eventually cruised along for 62ft 6in (19m) to win gold. There was a current in the lake that day, but athletes nobly took this in their stride – it was suspected to be sweeping them forwards in their direction of travel. He didn't know it at the time, but this would be the best Olympic plunge performance in history.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.