'The pressure change was causing me to have contractions': What it's really like to be a tornado chaser

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow tornadoes form remains one of nature's biggest mysteries. Meet the scientists who are chasing twisters to unlock the secrets of destructive storms.

"I realised it was very likely the tornado was killing people while I was collecting data," says Robin Tanamachi. "It gave a lot of gravity to the situation, and really drove home just how serious the work was that I was doing."

Tanamachi, a research meteorologist and associate professor at Purdue University in Indiana, vividly recalls her most memorable tornado. It was 31 May 2013 and she was watching an extremely large and powerful EF-3 tornado, with wind speeds of 295 mph (475 km/h), near El Reno in central Oklahoma.

The El Reno tornado, the widest tornado ever recorded, killed eight people, including three storm chasers.

"I just remember being extremely emotionally heavy at that point because I was seven months pregnant and the pressure change was causing me to have contractions," says Tanamachi.

Twisters

In the new blockbuster Twisters (out on 19 July), meteorologists stalk tornadoes ripping up towns in Oklahoma. In his review for BBC Culture, Nicholas Barber writes that although Twisters features charismatic actors and thrilling sequences, the film doesn't have much plot and mainly "has bland characters driving into bad weather, over and over again".

Just like in the new blockbuster Twisters, meteorologists such as Tanamachi chase powerful tornadoes across the US, searching for clues about their formation in an attempt to improve forecasts and warnings.

An average of 1,200 storms hit the US every year, according to the US's The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa). Over the past 10 years, the US has experienced between 908-1,818 tornadoes annually. In 2023, there were 1,423 tornadoes, which killed 83 people while 1,397 of these storms have claimed the lives of 39 people so far in 2024.

The strength of a tornado is measured by the damage it causes. And tornadoes can be extremely destructive.

With winds reaching up to 483km/h (300mph), tornadoes cause millions, sometimes billions, of dollars-worth of damage every year, and countless fatalities. (Find out whether tornadoes or hailstorms do more damage in this story by India Bourke.)

There are certain key atmospheric ingredients which combine to lead to tornadoes, including warm moist air near the ground, with cooler, dry air above, and wind shear, which increases the strength of the updraught and promotes the rotating vortex.

Destructive tornadoes spawn from "supercells", violent thunderstorms which form a rotating updraught and bring heavy rain, strong winds and large hailstones. A strong vertical wind shear leads to a horizontally rotating cylinder of air, which the updraught lifts within the supercell. The cylinder narrows, becomes stretched and starts spinning faster and faster, forming a tornado.

In the eye of the storm

Why some thunderstorms create violent tornadoes while others don't, largely remains a meteorological mystery. They are "rare, deadly, and difficult to predict", according to Noaa.

"Sometimes really perfect supercells will just not want to spawn a tornado for us, they'll just sit and spin," says Tanamachi. "And we're just sitting there, twiddling our thumbs and waiting."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTanamachi and other meteorologists are trying to understand "tornadogenesis" – the process by which a tornado forms.

"That's really one of the last unresolved mysteries in severe thunderstorm science, exactly what causes that collapse of the circulation into a scale that's concentrated enough to be called a tornado," she says.

"Every time we do one of these field programmes, we get a few more clues. But we also get more questions that we want to answer," she says. "It's a source of endless fascination and curiosity for all of us."

More like this:

• In a warmer world, tornado behaviour is changing

Karen Kosiba, a storm chaser and atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, says storm chasing is really important for understanding what creates these powerful rotating columns of air.

"We're trying to put portable weather stations in the path of a tornado, very close to the storm and get them very low to the ground," says Kosiba. This field data helps shed light on what is happening in the formation process – something which weather forecasting models alone cannot reveal, she says.

Weather models can predict the conditions that are ideal for a tornado to form, but often have difficulty accurately anticipating when and where tornadoes will appear.

"There's a synergy between the modelling and observations. You can't get everything from modelling and you can't get everything from observations but when you combine the two, you're able to build a better, broader picture of what is happening," says Kosiba.

Tornado season in the Midwest usually runs from March until late June. Scientists use weather models to identify "conditions that look favourable for storms that might produce tornadoes", says Kosiba. "We then try to get to that area, either the day or night before… We do a lot of driving," she says. "We're constantly repositioning ourselves."

Storm chasers have a very narrow window to gather their data. "The actual formation of a tornado often happens on a time scale of just a few seconds," says Tanamachi. Scientists usually only have about 15 minutes to get to the right location and set up their radars and monitoring equipment, says Kosiba. "It's hard to get measurements…There's a low probability of success," she says. "It's very costly, both monetarily and time-wise."

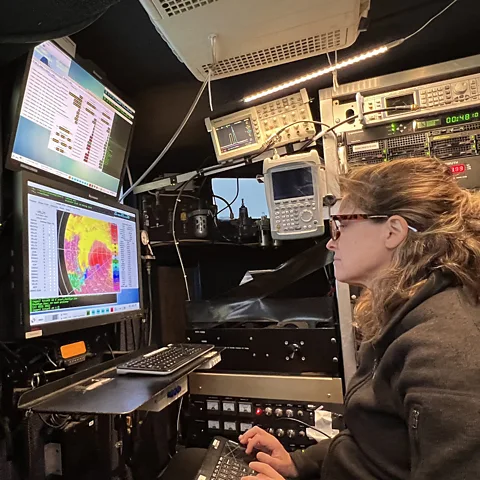

Jen Walton

Jen WaltonThere's much "more active decision making" involved when monitoring tornadoes, compared to hurricanes, says Kosiba.

Hurricanes extend across a wide area, up to 1,000 miles (1,609km) across, and scientists can usually predict their path three to five days before landfall, using models. (Read more about how hurricanes are intensifying rapidly in this story by Lucy Sherriff.)

Tornadoes are small-scale circulations, which rarely measure more than a few hundred feet across, and can last from several seconds to more than an hour. At the peak of the season, there can be more than 150 tornadoes reported across the US in a single day.

"Tornadoes are much harder to forecast than hurricanes," says Kosiba. "They're small-scale things happening in our atmosphere and it's challenging to know if the right ingredients will come together for that to happen."

Growing threat

Climate change is causing tornado season to change, both in duration and location. The geographic boundaries of where tornadoes occur is expanding and vast swathes of the US are racing to adapt. (Read more about how tornado alley is changing.)

Tornadoes typically occur in tornado alley, which is broadly synonymous with the Great Plains and includes Texas, Oklahoma, Nebraska and Kansas. But research shows that these states are seeing fewer tornadoes, while Tennessee, Georgia, Arkansas, Kentucky and Alabama are experiencing an increase.

Some scientists say that tornado alley is widening and migrating to the east and southeast of the US.

A 2023 study found that supercell storms will become more frequent and intense as temperatures rise. Supercells are projected to become more numerous in parts of the eastern US, while decreasing in frequency in parts of the Great Plains, according to the research.

And this shift concerns those who study these storms as tornadoes in the southeast are particularly deadly. Tornadoes there often strike at night during the winter months, resulting in more casualties and destruction.

Tornadoes are also harder to detect in the rugged, tree-covered southeast, than on the open expanse of the Midwest Plains, says Harold Brooks, a senior research scientist at Noaa's national severe storms laboratory.

The southeastern states have a higher population density, a greater number of mobile homes and more low-income communities, making them particularly vulnerable to tornadoes, he says. "So tornadoes in that area tend to be deadlier than tornadoes in the Midwest."

If a tornado forms in northern Alabama or Mississippi, it's more likely to hit a large number of structures, he adds. (Read more about the race to build tornado shelters outside tornado alley.)

But due to the forecasting challenges, tornado warnings are often only issued 10 to 15 minutes in advance. This means that when they occur at night, it can be very difficult to warn vulnerable communities in time and get them to tornado shelters, says Brooks.

"One of our big challenges is how to provide information to people living in poverty," he says, noting that they don't have weather radios at home. "It's like with every other disaster… poor communities tend to be harmed more [when tornadoes hit] because they don't have the resources to receive the information and respond."

Funded by Noaa, Kosiba and a team of researchers from universities across the US are gathering data from tornadoes in the southeast, in the hope that this will help improve forecasting and warnings in future.

"Tornadoes in the southeast are challenging and impactful. It's really critical [to gain a better understanding] because there are many people who are vulnerable," she says.

Storm tourism

Scientists aren't the only ones chasing supercells. They warn that there rising numbers of people are chasing twisters in their spare time. This is putting both amateur storm chasers' own lives and scientific research at risk, scientists say.

"Many people think that the tornado is the thing that you're trying to keep safe from. It's really not; it's the storm environment itself that's a lot more hazardous," says Tanamachi.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmateur storm chasers will often be tracking the path of the tornado on their phones, following weather radar apps, and this can lead to collisions, says Tanamachi. "Distracted driving and really bad conditions can combine to create a hazardous environment that has almost nothing to do with the tornado itself," she says. "More drivers in the US die on wet roads every year than the [total] number of people who are killed by tornadoes." Nearly 5,700 people are killed and more than 544,700 people are injured in crashes on wet roads annually, according to the US Department of Transportation.

In an average year, tornadoes result in the deaths of 80 people and cause 1,500 injuries.

"Storm tourism definitely hinders our scientific work," says Erik Rasmussen, a meteorologist and expert on convective storms at Noaa's national severe storms laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma.

"Most of us in the scientific community can see the writing on the wall, that this [scientific field research] is coming to an end: we cannot [achieve] the mobility and positioning we need to collect [our] data." In the future, scientists will have to rely on robotic devices to collect data due to the huge numbers of storm chasers gathering at tornado sites, says Rasmussen. "Some storms are now so congested that there is simply no way that we can do our research."

It is crucial that storm enthusiasts are guided by experts, allowing them to chase twisters in a safe way, scientists tell the BBC.

The situation can change very quickly, Kosiba warns. She recalls directing a team of scientists that were deploying weather stations at night in Kansas, during the 2012 tornado season. It was dark and the team were confused about where they were in relation to the storm. "Suddenly it got really, really windy for them…It turns out that they had actually already driven into the tornado twice," says Kosiba.

"Most people don't realise that sometimes the images on your radar app can be up to five minutes old, so you might not be in the safe position that the app suggests," says Tanamachi. She recommends that tornado enthusiasts join tours led by experienced storm chasers and scientists.

Tanamachi says she fully supports amateur tornado spotters, if they follow the safety guidelines, and understands what draws so many people to storm chasing.

"I compare the experience to watching a solar eclipse – it's almost spiritual," she says. This was her experience while watching a slow-moving tornado near Rozel, in Kansas, in 2013. "It was very photogenic – a slender, picturesque funnel in front of the sunset. We just sat and watched it for 30 minutes. It was really transcending and beautiful."

--

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.