How an English castle became a stork magnet

Knepp Estate

Knepp EstateHelped by a bold rewilding project, storks are migrating between Britain and North Africa again for the first time in 600 years. How can we make their journey safer?

It is a cool morning in March and I am wading along a muddy path, part of the vast, ancestral grounds of Knepp Castle in southern England. The scenery looks ancient and dramatic, a patchwork of well-trodden grass, deep puddles and tangled scrubs, studded with majestic, bare-branched oak trees. High up in the crowns of the trees are huge storks' nests the size of tractor wheels, their dark silhouettes contrasting with the pale blue sky. White storks glide through the sky and land in the nests, while others sit and warm their eggs. Every now and then, the air is pierced by a joyful clattering sound as they greet each other.

"We sometimes describe this as stork headquarters," says biologist Laura Vaughan-Hirsch, gesturing at the nests around us. She leads the White Stork Project at Knepp Estate, which started in 2016 and is part of a wider stork reintroduction project in southern England. As we talk, a stork in one of the highest nests climbs on top of another: "They're mating," says Vaughan-Hirsch. A short while later, a clattering sound is heard from the nest, which is, she explains "all part of the bonding".

From 30 injured wild storks who were brought over from a rescue project at Warsaw Zoo in Poland, looked after at Cotswold Wildlife Park and then introduced into the rewilded habitat at Knepp, the white stork colony has grown to 80 at its peak, she says. It is thought to be the first time wild storks are breeding in Britain in 600 years. (You can in fact observe one of the nests yourself, via a live camera feed.)

Knepp Estate

Knepp Estate"The first time I saw them here, it was a bit like Jurassic Park really, the way they were flying over your head," says Amy Hurn, a volunteer who has been helping monitor the birds for two years. "I had never seen a white stork in the wild before, I never knew that that was near to where I live."

Since 2019, the younger birds have started migrating – adding a whole new dimension to the project. A number have been equipped with trackers, allowing the team to trace their epic journeys. Their travels are connecting Knepp Castle with storks' wintering sites as far as Spain, Portugal and Morocco. But in the process, new hazards to the rebounding population have emerged, including collisions with power lines.

This poses another challenge for those keen to protect England's new stork community: how do you go from providing suitable nesting sites, to helping the birds travel safely and find supportive habitats across a whole continent?

Knepp Estate

Knepp EstateA muddy paradise

No one knows for certain why storks disappeared from the British Isles, where the last nesting pair was recorded on the roof of St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in 1416. Hunting may have played a role, says Vaughan-Hirsch, alongside habitat loss, as wetlands here and elsewhere in the world were drained.

"Just over 20 years ago this would all have been agricultural land, managed with machinery and pesticides," says Vaughan-Hirsch, gesturing at the scrubs and trees around us.

In the early 2000s, the owners of Knepp, Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree, decided to rewild their land. They let brambles and other scrubs grow freely, then introduced free-roaming deer, pigs, Exmoor ponies and hardy cattle. As we walk, small birds fly in and out of the thorny thickets, which provide safe nesting sites for critically endangered nightingales and turtle doves. Vaughan-Hirsch stops mid-sentence to point out a red kite swooping through the air.

The trampling, nibbling herbivores have created the tidy-looking grassy areas around us, Vaughan-Hirsch explains – and the rootling pigs are responsible for the muddy puddles, some with storks' prints leading into them. At this time of year, you will see storks following around the cattle and pigs, waiting for the earth to be turned over, says Vaughan-Hirsch.

"Storks will take any invertebrates at all," she adds, including earthworms and larvae: "They'll take surprisingly small prey items, anything that comes up with the mud."

Jamie Craig, Curator at Cotswolds Wildlife Park, sees the rewilding project as crucial for the storks' return. "The insect life is phenomenal," he says, about Knepp. "So for a start, the food is there. The habitat is right, you've got big trees, you've got open areas, you’ve got livestock moving around through that, which disturbs the insects." He concludes: "The core area at Knepp is just perfect for storks."

At one point, storks even built nests on Knepp Castle itself – or rather, one of the two castles, as there is also an older, ruined castle in the grounds. The team have also found ringed storks from continental Europe showing up among their own, says Vaughan-Hirsch: wild storks who flew across the channel and, being a social and gregarious species, appeared to be attracted by the colony.

Knepp Estate, Cotswold Wildlife Park, University of East Anglia

Knepp Estate, Cotswold Wildlife Park, University of East AngliaAn epic journey

Come autumn, Vaughan-Hirsch says, most of the young storks show their genetic urge to migrate. They soar and circle higher and higher, using rising thermal currents to rise and then glide – storks are among the world's highest-flying birds. Some of the migrating storks carry trackers. Bird fans across Europe and North Africa have also sent in sightings, after spotting their numbered identification rings.

"We thought: 'It's going to be ages before this happens'," says Craig of the Knepp storks' migration, given that they had been bred from the captive rescue birds. He and his team brought over the rescue storks from Poland and still keep a non-flying, breeding population at Cotswold Wildlife Park, with fledglings released into the colony at Knepp. Another free-flying colony has been introduced to Wadhurst Park in Sussex, but they have not bred yet.

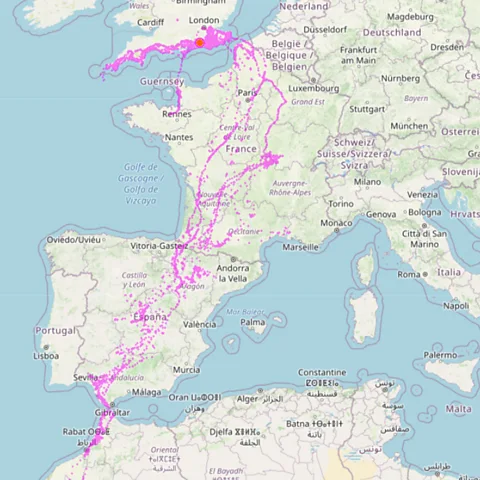

The day after my visit to Knepp, I speak to Aldina Franco, an associate professor in ecology and global environmental change at the University of East Anglia. She helps track the Knepp storks and shows me maps of their migration routes, based on data from birds with a tracker.

The multitude of tracks show a surprisingly clear overall pattern, of storks zipping back and forth along the south coast of England, trying to figure out where best to cross the channel, then zooming across the water to France and down to Spain, Portugal and Morocco.

Storks generally try to choose the shortest route across water, research suggests, since they can't use their usual soaring flight strategy there as thermal updrafts over water tend to be weaker than on land. They therefore need to flap their wings to cross water, instead of just gliding. As this is tiring, they look for the shortest crossing – and the tracking lines indeed show most of them choosing the shortest stretch of water, between Dover in England and Calais in France, Franco points out.

There are some exceptions, however; one stork ended up on a fishing vessel in Cornwall and used it to travel to the west coast of France, she says.

Once they reached the other side, the storks appeared to instinctively use a tactic common among young wild storks: follow more experienced wild storks. As young storks join the flocks along the way, the travelling flocks can swell to hundreds of storks all flying and circling up the thermals together, in one of nature's great spectacles.

Knepp Estate

Knepp EstateOn the move

To celebrate the current spring migration season, you can follow the movement of billions of birds with stories from BBC Future Planet. Be sure to check back and join us as we explore how we can all help birds travel safely on their epic migrations.

The trip comes with hazards, however. Around a dozen of the Knepp storks have died during migration, Vaughan-Hirsch says – half of them through collisions with or electrocution by electricity pylons and power lines.

Such collisions are a huge risk and can cause death or severe injuries – and indeed caused some of the injuries in the original rescue birds from Poland, says Craig. The storks' size also makes them vulnerable to electrocution, he says: "When they open their wings, they are in connection with other lines, other parts of that structure". This causes the electricity to flow through them. "Generally, if a stork's electrocuted, that's pretty much the end of the stork, unfortunately," he adds. Power lines and pylons also endanger other large birds such as bald ibises, eagles, vultures and owls.

Yet safety measures can help. Research from Poland, a country with a large stork population, suggests insulating the pylons could cut electrocution-related stork deaths to zero. A European non-profit network of so-called stork villages – villages that protect storks – also reports that in places with insulated electricity pylons, there were no more electrocution deaths.

Having reached Portugal and Spain, or crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to Morocco, some of the Knepp storks enjoyed a hearty reward: a feast on open landfill sites, rich in food waste. In Morocco, a retired vet and bird fan in the area is observing them and sends snapshots back to Knepp, say Hurn and Vaughan-Hirsch.

"It's a bit grim but it's easy pickings and they'll see a lot of other storks hanging out there so they will stop off," says Hurn. With a smile, she adds: "They're on a very long gap year, and it's the best bar in town."

The Knepp storks are not the only ones attracted to these sites, says Franco: "The landfill sites in Portugal, Spain and Morocco are feeding storks from Germany, the UK, France – all the storks that use the western migratory routes." There has been a trend among Portuguese storks to use these landfill sites year-round, and no longer migrate to Africa as before, research by Franco and her colleagues shows. Despite hazards such as plastic, she suggests the landfill sites can be a useful source of food.

Knepp Estate

Knepp EstateHow you can help the spring migration

Here are two simple ways you can help, according to bird conservation experts:

Switch off non-essential outdoor lighting to reduce confusion and crashes.

Pick up litter and avoid littering – litter can be dangerous for birds when mistaken for food and swallowed.

How storks can thrive

At Knepp, at least one stork has already returned from migration and the hope is that more will eventually come back north to breed, which usually happens around the age of five, says Vaughan-Hirsch.

For gardeners keen to get involved in helping birds, but without space to house a full stork colony, Craig has a tip: start with bugs and worms, which are vital food sources for birds. Leaving logs to rot in your garden, leaving an area unmown, allowing drystone walls to tumble down: all this helps create useful micro habitats, he says.

More like this:

In these habitats, he explains, "insects proliferate, and bird life and reptile life is going to do better. These tiny steps can make an enormous difference."

The European stork villages also feature walking trails where the storks can be observed, and Knepp offers guided "stork safari" walks as well as having freely accessible public footpaths from which one may see flying storks. Vaughan-Hirsch, a former science teacher, says she particularly enjoys visiting schools and hosting school classes to talk about the storks. She hopes that migration will create new connections not just for the storks, but also, for those protecting them.

"The plan for the project is to connect people across those migratory pathways and then start talking about habitat recovery across the continent, rather than just in this county. That's the dream, really."

With a last look at the storks' nests, which are generally reused and refurbished over generations, she adds: "I love the thought that these nests will still be here long after we are gone."

--