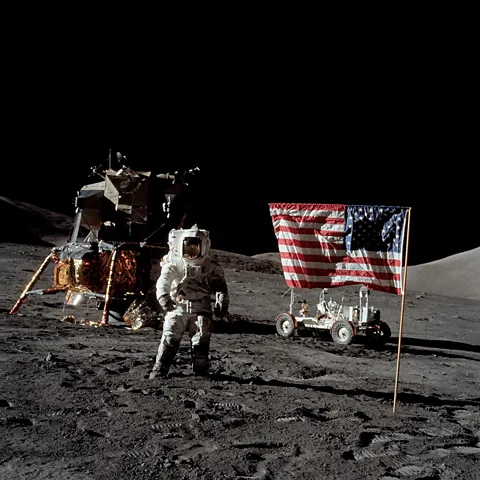

Moon Race 2.0: Why so many nations and private companies are aiming for lunar landings

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFive decades on from the last of the Apollo missions, the Moon is once again a target for space exploration. But Nasa no longer has lunar exploration to itself.

The number of astronauts who walked on the Moon hasn't changed in over 50 years.

Only 12 human beings have had this privilege – all Americans – but that will soon increase. The historical two-nation competition between the US and Soviet space agencies for lunar exploration has become a global pursuit. Launching missions to either orbit the Moon, or land on its surface, is now carried out by governments and commercial companies from Europe and the Middle East to the South Pacific.

Despite the success of the US Apollo missions between 1969-72, to date only five nations have landed on the Moon. China is one of the most ambitious of the nations with the Moon in its sights.

After two successful orbital missions in 2007 and 2010, China landed the unmanned Chang'e 3 in 2013. Six years later Chang'e 4 became the first mission to land on the far side of the Moon. The robotic Chang'e 5 returned lunar samples back to Earth in 2020 and Chang'e 6, which launches in May this year, will bring back the first samples from the Moon's far side.

The country's ambitions don't stop there. "China is openly aiming to put a pair of its astronauts on the Moon before 2030," says space journalist Andrew Jones, who focusses on China's space industry.

"There is demonstrable progress in a number of areas needed to perform such a mission, including developing a new human-rated launch vehicle, a new-generation crew spacecraft, a lunar lander and expanding ground stations," says Jones. "It is a tremendous undertaking, but China has demonstrated that it can plan and execute long-term lunar and human spaceflight endeavours."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNot surprisingly, recently announced delays to US space agency Nasa's own Moon programme Artemis, which has pushed back plans to land astronauts on the lunar surface to September 2026 at the earliest, has produced the phrase "Moon Race" between the US and China.

"I think that China has a very aggressive plan," Nasa chief Bill Nelson told a media teleconference about the amended Artemis timescale. "I think they would like to land before us, because that might give them some PR coup. But the fact is, I don't think they will."

China, of course, may also experience slips in its launch schedule. "China needs a super heavy-lift launcher to start putting large pieces of infrastructure on the Moon," says Jones. "Its Long March 9 rocket project has undergone changes, so this may delay first missions from 2030 into the early or mid 2030s."

India became the fourth nation to land on the Moon with the unmanned Chandrayaan-3 in August 2023, which touched down close to the lunar south pole. After its success, the chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) announced it aims to send astronauts to the Moon by 2040. (Find out more about the mysteries of the lunar south pole and why so many nations want to land there in this feature by Jonathan O'Callaghan.)

Meanwhile, Japan's Slim (Smart Lander for Investigating Moon) mission recently placed its Moon Sniper lander on lunar soil to become the fifth nation on our nearest neighbour. The Japanese space agency, Jaxa, is also nearing the end of negotiations to put a Japanese astronaut on the Moon as part of the US Artemis programme.

Other countries – such as Israel, South Korea and numerous member states of the European Space Agency (Esa) – have also placed robotic spacecraft into lunar orbit. Nasa recently announced that the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) would provide an airlock for Gateway, its planned lunar orbiting space station for the Artemis missions.

The reasons for going vary: from scientific knowledge and technological advances to the prospect of accessing potentially useful lunar resources and political or economic value. The UK space industry, for instance, was extremely robust during the recession.

But in such a crowded field, the big question is who will become the next major global player in the next phase of lunar exploration. It will no longer be the sole preserve of national space agencies; commercial companies also want a piece of the lunar action.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough China launched the first commercial mission to the Moon in 2014, the small privately funded Manfred Memorial Moon Mission was a microsatellite (61cm x 26cm x10cm) for a lunar flyby built by LuxSpace in Luxembourg. America's first planned commercial lunar mission, however, was much more ambitious.

In January this year, Astrobotic, a company based in Pittsburgh, launched Peregrine Mission 1. It was to be the first US spacecraft to land on the lunar surface since Apollo 17 in 1972. Unfortunately, a "critical loss of propellant" shortly after launch meant that it had to return home without landing and burned up in the Earth's atmosphere above a remote part of the South Pacific Ocean.

As a result, the upcoming US commercial mission, Intuitive Machines IM-1, which launched on 15 February and intends to place its Nova-C lander on the Moon, has been bumped up from second to potentially first place.

"As partners in advancing lunar exploration, we understand and share the collective disappointment of unforeseen challenges," says president and CEO of Intuitive Machines, Steve Altemus. "It is a testament to the resilience of the space community that we continue to push the boundaries of our understanding, embracing the inherent risks in our pursuit of opening access to the Moon for the progress of humanity."

The US declared the Moon a strategic interest in 2018. Does Altemus see his commercial mission as the beginning of a lunar economy? "At the time, no lunar landers or lunar programs existed in the United States," he says. "Today, over a dozen companies are building landers, which is a new market. In turn, we've seen an increase in payloads, science instruments, and engineering systems being built for the Moon. We are seeing that economy start to catch up because the prospect of landing on the Moon exists. Space is an enormous human endeavour and it will always contain a government component because they have a strategic need to be in space. But there's room now, for the first time in history, for commercial companies to be there."

In recent years India has also seen a boom in space start-ups such as Pixel, Dhruva Space, Bellatrix Aerospace and Hyderabad's Skyroot Aerospace, which launched India's first private rocket in 2022.

Nasa

NasaIn October 2023 an Australian private company, Hex20, announced a collaboration with Skyroot Aerospace and Japan's ispace, which will attempt its second robotic lunar landing at the end of this year. The collaboration aims to stimulate demand for affordable lunar satellite missions.

But when it comes to the Moon, footprints and flags on the ground still generate the biggest headlines. The four astronauts who will go into lunar orbit on Artemis II – Nasa's Christina Hammock Koch, Reid Wiseman and Victor Glover plus Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen – all feature in London's immersive Moonwalkers show.

You might also like:

Written by British filmmaker Chris Riley and actor Tom Hanks (who famously played astronaut Jim Lovell in the Apollo 13 movie), it highlights the collective Nasa effort required to put astronauts on the Moon and looks ahead to Artemis doing the same.

I recently watched the show sat alongside an upcoming guest on the Space Boffins podcast: former Nasa Apollo flight director, Gerry Griffin. Afterwards he described the Artemis programme as "wonderful".

"I'm worried about the funding," he says. "It's going to always be a problem."

But Griffin is optimistic and full of confidence in its astronauts. "We got the best. They are really, really good. But we've got to get going. It's time we get back."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.