A leading data scientist's journey from doomism to climate hope

Angela Catlin

Angela CatlinData scientist Hannah Ritchie argues that planetary damage could be about to peak – but that the US election result could be "pivotal".

In a global survey of young people's feelings about climate change, half recently told researchers that they believe "humanity is doomed". In other words, they don't believe that the needs of the current generation can be met without undermining the next. They worry that life as we know it is not sustainable.

Data scientist Hannah Ritchie once believed likewise. As a teenager, she feared that humanity's ravaging of the planet – via everything from climate change to deforestation and overfishing – presented a series of unsolvable problems. Her undergraduate degree, begun at Edinburgh University aged just 16, only seemed to confirm these concerns. "I used to be convinced I didn't have a future left to live for," the now 30-year-old writes in her first book, Not the End of the World.

Today, however, Ritchie feels differently. While she's still worried about the trajectory the world is on, she believes there's hope humanity can turn things around. As deputy editor at Our World In Data and a senior researcher at the University of Oxford, she points to developments and statistics that tell a more optimistic story, from improving air quality to rising EV sales.

Ritchie speaks to BBC Future Planet about what shifted her mindset, why the world might be reaching overall "peak pollution" – and ways that a more sustainable future could be secured.

What prompted you to change your mind about humanity's future? And why do you now think that "doomist" predictions do not inspire action?

Climate change has always been part of my life and I've always been quite worried, even as a kid. That got worse when I went to university, because I was studying environmental science and all the trends were very much going in the wrong direction. At the time I felt very anxious, hopeless, and like these problems were completely unsolvable.

A key turning point for me was discovering the work of the Swedish physician and statistician Hans Rosling. When I was studying, I'd assumed that all of the human wellbeing metrics – such as global poverty, mortality and hunger – were also getting worse alongside the environmental ones. But Rosling would do TED talks where he'd show, using data, how the world had changed over the last few centuries for the better.

So, I started asking: can we do both things at the same time? Can we continue to improve human wellbeing while also reducing our environmental impact? And, over the last 10 years or so, according to the environmental data, there have been signs for cautious optimism. It's not inevitable that we get there, but I think there's the opportunity for us to do so.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe problem with doomism is not people thinking that climate change is a really serious problem – because that's also what I think. It is the idea that it's too late to do anything about it. I think the science is very clear that it's never too late; the impacts of climate change are on a spectrum and where we land on that spectrum depends on what we do today. The more action we take, the more climate damage we limit.

The feeling of "it's too late" just leads to inaction and paralysis. And I know, from feeling that way in the past, that it didn't actually make me very effective in driving solutions forward.

Air pollution, climate change, forests, food, biodiversity, ocean plastic and overfishing: all pose vast threats to human and planetary health. But your data analysis has given you hope that a greener future is possible. So what do you think has been the most powerful instance yet of humanity's ability to change for the better?

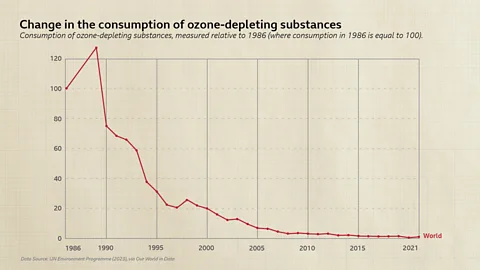

The ozone layer was the climate change problem of its day, and we don't talk about it anymore because it's a problem that we solved. We have reduced the emissions of ozone depleting gasses by more than 99%.

UNEP

UNEPIt's easy for us to look back now and say that was inevitable. But I think people working on this at the time, faced really strong pushback from governments, as well as from industry, who denied that it was a problem. You see lots of parallels between that and climate change today.

Another example is acid rain. This was a big environmental problem that, especially across Europe and North America, we've done a really good job of tackling.

Sign up to Future Earth

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers. In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

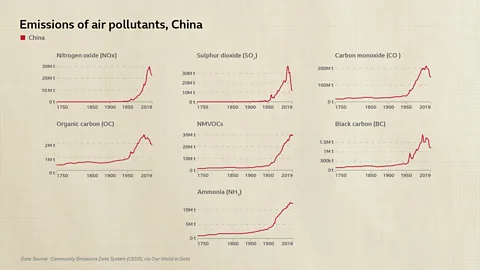

On air pollution more broadly, while it is still a massive health problem, we have seen progress. In rich countries in particular, public policy has been very effective at driving down local air pollution. And China has managed to dramatically reduce levels in many of its cities in a very short period of time.

Your book gives numerous examples of the green transition already underway around the world.

There's the possibility we could be approaching peak deaths from air pollution, with rates falling even as the number of people in the world continues to rise. There's your optimism that total emissions will peak in the 2020s, with global per capita CO2 emissions already having done so. There's the passing of peak deforestation. The passing of peak agricultural land. And the reaching of peak petrol car sales.

In light of such trends, would you say that the planet has already reached overall "peak pollution"?

That requires aggregating across many different metrics. I'm going to say we're very close to peak pollution. We're very close to peak CO2 emissions: we've been on a plateau for a number of years and I hope we peak and decline soon. On air pollution, we could be very, very close to the peak. And we've passed the peak on some air pollutants already – such as sulphur dioxide, which causes acid rain.

Community Emissions Data System

Community Emissions Data SystemWe've also peaked on small but significant things like the global sale of combustion-engine cars. So, there are a range of smaller peaks that then build up to get a macro-level peak of pollution.

You speak a lot about the positive power of new technology and technological progress. For example, the fact that solar power has gone from the most to the least expensive energy source in just 10 years. What is most helping humanity to unlock peak pollution?

The falling cost of low carbon energy – in particular solar, wind and batteries – is essential for us to peak and reduce CO2 emissions. To make progress, these technologies need to be competitive with or cost less than fossil fuels. Without doing that, our hopes of tackling climate change would be really low. So it is good news that many are already cost competitive.

What is the biggest barrier to reaching peak pollution?

A major factor limiting progress is the lack of investment in the energy transition and clean technologies by fossil fuel companies. They generate extremely large profits that they could re-invest in forward-looking solutions, but they are failing to do so. That doesn't mean ending fossil fuels tomorrow, but it does mean investing in a clean energy future.

Another challenge in reaching peak pollution – in terms of both CO2 emissions and air pollution – is the levels of energy poverty in the world. In rich countries, pollution is falling, but it is still rising in low and middle-income nations. That's because you've got billions of people who, quite rightly, want a higher standard of living. For these countries, the priority is not necessarily how to keep pollution low, but how to supply energy quickly and cheaply.

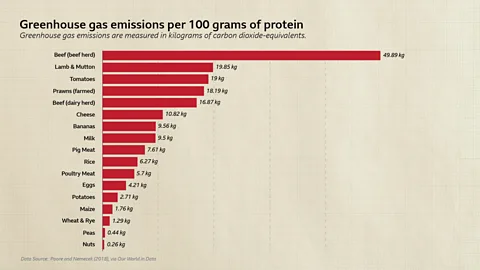

Meat-heavy diets pose a particular challenge to passing peak overall pollution – whether that's seen in terms of deforestation or emissions. What would you say to politicians who are wary of telling people what to do when it comes to their diet?

I'm much more optimistic on energy transition, and less so on the food system side. Many individuals don't really care where their energy comes from. They might protest the building of a wind or solar farm, but most people don't mind as long as energy is cheap and reliable.

Whereas diet is a very personal thing. It's strongly tied to our identity and individual behavioural changes are harder to make than technological ones. I'm sceptical we'll see a long term and large-scale shift to plant-based diets without quite significant technological advances – which can provide people with meat-like products.

Poore and Nemecek

Poore and NemecekIn general, I'm also very cautious of telling people what they should do. Prescription is ineffective – especially on what people eat but also more broadly. So, for politicians, it's a very fine line to tread. How do you show people the impacts, and the alternatives, but without forcing it on people?

Other figures who, like you, emphasise the importance of technology and possibility of continued economic growth, have been termed "ecomodernists". And some of the high-tech solutions that this group advocate – from nuclear power to agricultural intensification and cultured meat – have sparked concerns.

Is ecomodernism a phrase you identify with? And what would you say to those who warn that sometimes relying on new technology can accelerate environmental decline?

There's probably a range of definitions of what an ecomodernist is. For me, technology is just a really strong lever. I don't think technology on its own will save us, but when you're trying to scale solutions for 8 billion people, you need it.

Often people try to reach for solutions from the past. They might have worked for a small population of millions, but they don't scale to a population of billions. In agriculture, for example, you can't feed eight billion people without strong technological changes and without increases in crop yield - which we've seen from technological innovations. I'd also push back on nuclear being a new technology: it's been around much longer than solar and wind.

You might also like:

If you were to argue that we need to massively shrink individual demand on the planet's resources by changing our behaviours, you would still need a strong technological component. Even if energy demand is lower, for instance, you will still need a lot of solar, wind and batteries. And you'll still probably need nuclear or geothermal or hydro to provide a balance on the grid.

So, I think there's often a false dichotomy. Even in a world where you must reduce demand, you still need really strong technological developments.

Both businessman Bill Gates and American journalist David-Wallace Wells have hailed you as the "Hans Rosling" of the environmental movement, based on your optimism about the world's potential for positive development. Others however, have cautioned that figures like Rosling go too far in their optimism, and that averages can obscure underlying inequalities between and within nations. How mindful are you of these risks?

We can't just look at global averages. In our work at Our World in Data, we show data metrics across countries, not just the global average. This often reveals that, while there are still really large inequalities, on the human-side things are getting better.

Carbon Count

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 0g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

And finally, you also emphasise that individual behaviour change is no good without systematic change in our wider politics and economies. How hopeful are you, at the start of 2024 with a year of elections ahead, that the world will keep up its positive trajectory on peak-pollution?

I think it's a decisive year. I'm quite worried about a few elections: the US [result] will be pivotal. It could significantly slow down the nation's transition – and how other countries respond – if it steps back from climate action. So, it is important that the economic incentives for the energy transition are there. When such incentives exist, this stuff can start to happen even without strong political support. We need to build solutions and setups that can withstand swings from one political side to the other.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat makes you most hopeful?

The number of amazing people from so many disciplines all working on these problems. I felt very helpless when I felt like I was alone and others weren't working on this. Yet now the picture has changed dramatically. That's what makes me most optimistic we can get there.

--

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers. In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.