What the ‘future histories’ of the 1920s can teach us about hope

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHistorian Thomas Moynihan explores what we can learn from the hopeful and 'flagrantly fictional' forecasts written 100 years ago, just as humanity was emerging from a global pandemic, the end of the First World War and encountering rapid technological change.

From Hunger Games to Squid Games, from Black Mirror to Blade Runner, the appetite for dystopia seems higher than ever. Perhaps this is because the cliches of the genre are seeping beyond fiction. Both Elon Musk's Neuralink and Mark Zuckerberg's Metaverse seem lifted straight from cautionary tales. Meanwhile, AI poises unprecedented challenges, and human-made climate change threatens to destabilise our fragile world order.

Dystopian fiction can be vitally important. It can contain important warnings: raising alarms on social issues through extrapolating troubling trajectories. But in relentlessly imagining the future as already lost to dystopia in our fiction, it's possible we risk giving up on it in reality too.

As we now look ahead across 2024 – and the years, decades and centuries that follow – could there be other ways of thinking about the future?

The obvious response is a utopian lens, but this also has its flaws. Although utopias can expand minds, they also can tempt those too bewitched by them to act rashly or harmfully, by forcing their hopes upon the present.

As a historian who studies how worldviews transform and priorities alter as we learn more about ourselves and our place in the Universe, I'm interested in how people's perceptions of the future have changed over time. If we look back 100 years, how was tomorrow imagined back then? A century ago, there were dystopias and utopias, but many writers and thinkers also approached the future in other ways: with an open, nuanced and often playful perspective. And they did so despite the grave challenges they faced in their societies. What might we learn from these visions?

Getty Images

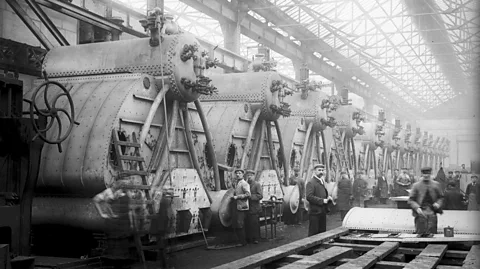

Getty ImagesPicture a world where horrifying war rages in Europe and the Middle East; where a pandemic has gripped the globe; where the masses suffer a deteriorating climate, while sweeping inequality jars against unprecedented wealth. A world where protest flares in the name of social justice, revolting against oppressive pasts and corrupt monopolies. A world where emerging technologies seem set to disrupt society's foundations, whether by automating away swathes of labour or, worse, precipitating universal catastrophe.

This doesn't just describe how some people view our present. It paints a picture, too, of affairs a century ago, as the 1910s shaded into the 1920s. Witness to World War One’s mechanised massacre, alongside a deadly pandemic, the period saw rapid developments in science, promising the unloosing of powers that were arguably even more disturbing.

Where we have climate change, they had smog and slums. Where our phones and feeds make us point-blank witnesses to the world's tragedies, they were, thanks to a newly coalesced global news network, the first generation to experience disasters as mass-media spectacles, like the sinking of HMS Titanic. Where they saw growing numbers of multimillionaires (one of which perished in the aforementioned shipwreck), we anticipate the first trillionaire. Where, today, geopolitical stabilities seem to be unravelling, they witnessed the spread of new authoritarian regimes.

You may also like:

Understandably, back then, there was similarly a burst of dystopian fiction. There were chilling visions of tech-fuelled totalitarianism, where Earth's oceans are filled in and its mountains levelled, whilst humans become drones serving like neurons powering one centralised, mechanised mega-brain. There were even prescient visions of climate disaster. Take, for example, Alfred Döblin's 1924 Mountains, Oceans, Giants: it depicts a high-tech future suffering overpopulation, where a plan is formulated to melt Greenland's icecap to create more living space. A mysterious, newly discovered form of energy is wielded to accomplish this, with disastrous results, as it unleashes all-consuming environmental cataclysm, rippling across the Northern hemisphere.

Nonetheless, there was resonant hope, too. Hope that the juggernaut of civilisation could be steered: that its technological forces — unloosed by the genie of science — could be collectively and equitably harnessed for the betterment of the world. Theirs was a generation whose future seemed torn between hope and dystopia, between renovation and final calamity.

Comment & Analysis

Thomas Moynihan is a historian and author. Currently, he is a Visting Researcher at Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

Amid the dystopias, there remained widespread conviction that technology could be harnessed, in harmony with the natural world, to emancipate, rather than to suppress, humanity. Speaking to a crowded hall in Yorkshire in 1923, Keir Hardie — who founded the UK's left-leaning Labour Party in 1900 — directly compared science's empowerments to those of his movement. He noted how physicists had recently discovered entirely new forms of energy, from X-rays to radioactivity.

Harnessed properly, Hardie suggested, these powers promised everything from medical miracles to unshackling abundances of unpolluting energy. Directly comparing such scientific revelations to Labour's struggle for worker's rights and protections, he declared that the formation of Britain's nascent welfare state may similarly set free hitherto "undreamed-of powers and forces in human nature".

Such statements might chime discordantly now "technology" often appears indistinct from "big tech", and more a totem for growing inequality than egalitarianism. However, back then, the wedding of technological innovation to private interests and profiteering was weaker, and therefore less ingrained in public consciousnesses. It reminds us that such expropriation, perhaps, wasn't historically inevitable and, therefore, doesn't necessarily need to forever continue.

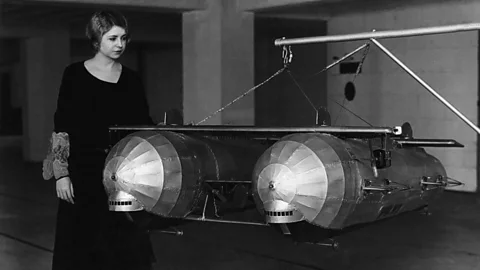

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy World War One's end, it was no longer questionable that science was poised to change everything, from work to warfare. Technology promised more of the same: colossal change. But it seemed, more than before, this could go in multiple directions, no longer bound to one bright destiny or dark fate. Recent shocks acted like a prism, splitting the path into tomorrow from one track into many, each leading towards dramatically different destinations, all now seemingly plausible from the present's vantage. Stranger and more multifarious prospects than those considered merely a generation before now couldn't be ignored.

This spirit was embodied in a popular British book series, called To-day and To-morrow, the centenary of which was marked in late 2023. Each entry staged a flourish of prophecy, plotting possible transformations within human affairs, in plucky and often provocative style. Areas you'd expect, from transport to technology, were treated, but entries also appeared on the futures of swearing, poetry, clothes, nonsense, and laughter. (Read more: 'To-day and To-morrow': The 100-year-old book series that predicted a wild and wonderful future.)

One 1929 entry, by the pacificist Vera Brittain, captures the series' virtuosic tone. After decades of coordinated protest and painful struggle, women had only the previous year been universally given the vote in UK. Brittain took the opportunity to project this forward: forecasting the future of gender relations.

Titled Halcyon, or, the Future of Monogamy, it begins with Brittain drifting to sleep, and dreaming she is reading a "moral history destined to be published in the far-distant future". It's by "Minerva Huxterwin", the "Chair of Moral History at Oxford" (a position which didn't, and still doesn't, exist). Apparently living and writing many centuries hence, Huxterwin's specialism is chronicling the 20th Century's moral revolutions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe rest of Brittain's book is her transcription, upon awaking, of what she dreamt reading. Of course, it's all a ploy; Huxterwin is made-up. But it's ingenious, allowing Brittain to proffer her preferred vision of what could be, using a dreamt-up historian from centuries hence as her mouthpiece.

Her hopeful vision partially panned out. Narrating Brittain's future, from her further future, Huxterwin chronicles how household technologies, introduced from the 1930s onwards, renovate gender relations throughout the 20th Century. And no longer oppressive, now mutually enjoyable, Huxterwin records marriage surviving well into the future, albeit only through being continually transformed.

Brittain's wasn't the only "future history" of the time. Many bold prophecies would, back then, often be winkingly presented as the reflections of commenters from centuries hence. Perhaps the most celebrated example was Edward Bellamy's bestselling Looking Backward, which, though first published in 1887, experienced a resurgence in popularity through the 1930s. It relayed reflections transmitted from the socialist idyll Bellamy boldly imagined America would become by AD 2000.

This generation wasn’t the first to use the device of the future historian. During the height of their empire, Victorians liked to spook themselves envisioning how, in some misty future, travelling archaeologists, from distant lands, may decipher London's decayed ruins. Often these visitors were envisioned as indigenous peoples from other continents – now imagined in the position of imperial ascendency – in a move designed to scandalise the racist sensibilities of Victorian England.

The Victorians’ use of future history, however, constricts imaginations more than expands them. It frames the future as set, with time on one track, composed, in this instance, of rising and falling of empires and ascendancies. The tempo might have varied, but not the tune. Skipping ahead this way allowed writers to claim things could not have gone any other way. Tidily pruning paths untrodden, insinuating they were never live options anyway, this makes time’s course seem sealed from what’s unforeseen or unforeseeable.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Brittain and others imagined future historians, they were actually drawing from a tradition practised by earlier writers like Joseph Addison, which opened rather the closed minds. In 1711, Addison pondered what "impartial" assessment a future historian might make of the controversial politics of his time. His prediction is knowingly derailed, though, as Addison interrupts himself, segueing into glaring partiality: his future historian ends up writing about posterity's esteem for Addison himself.

It's a self-aware joke. But it's doing more than highlighting how prediction is coloured by the person making it. In so flagrantly flunking impartiality, Addison is not just staging the ironic failure of his own prevision: he's also foregrounding the fallibility of all such attempts to capture the future. After all, tomorrow's attitudes will always differ from our forecasts.

The future histories of the 1920s inherited far more from Addison’s whimsy than Victorian angst. Previsions like Brittain’s were presented as blatantly made-up. Flagrantly fictional, they flaunt their pretence with a wink. As well as allowing these authors to criticise their present's limitations, inequalities and bigotries with more freedom, it also opened a space for multiple possibilities to coexist. Claiming to assume the role of future historian is patently absurd, an impossible feat. But because we all know this — audience and author alike — we understand we have strayed from the business of making serious claims about what will happen, and drifted into the wider, looser terrain of what could. Our focus has dilated, expanding from what's most probable to what's merely possible. To predict is, often, to prescribe; to propose, however, is to enter dialogue and play.

To be clear, the future-gazers of 100 years ago often got things gravely wrong. But even here, we can gain insight. Living in the 2020s, we find ourselves living in the "tomorrow" many prophets from a century ago attempted to anticipate. We now can, like the chroniclers they imagined, look backward and assess. This reveals plenty of optimistic predictions for, say, technologies that never emerged – but also anticipations of avenues that we should be thankful history didn't take.

Take, for example, 1911's Moving the Mountain: a feminist utopia envisioned by the prominent suffragist Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Through a contrivance involving amnesia, our narrator finds himself awoken and thrown into the America of decades hence. It is unrecognisable; there are two-hour workdays; women are entirely emancipated; civilisation now powers itself via "solar engines". There, also, is no crime or poverty. But this is because, in Gilman's chilling words, "degenerates" have been sterilised and "removed".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Gilman's future, "equality" has been reached. But it has been reached not through emancipating, but rather by brutally eliminating, the downtrodden and those she deemed unfit. Gilman, like many others in the 1920s, was falsely convinced by the ideas of eugenics, and that "moral character" is strictly inherited rather than being shaped by one's environments or upbringing.

A few, like Brittain, saw past this. Her future historian chronicles a world wherein eugenics is never entertained, because society recognises that youngsters' destinies are dictated not by their genes but are shaped, overwhelmingly, by equal opportunity and parental affection.

Nonetheless, eugenic views remained widely acceptable in this period, eventually coming to influence policy globally, from the United States to Japan. Classist and racist paranoias, about "bad stock" outbreeding "superior" classes, slither through forecasts from the era. So too do prescriptions we now know to be heinous. These went on to harm innumerable real people. Had they been implemented more fully, many of us wouldn't be here today.

There's a resounding lesson here. Only a few generations ago, influential people, who were convinced they were benevolently acting in the name of future generations, were led to disastrously evil conclusions, because of misguided beliefs and unrelinquished bigotries in their present. This should give us pause when anyone speaks for the future today.

Prediction is a vexed game. So is prescribing which future is best; not just for people like yourself, but for everyone. That's why we ought to be suspicious of all visions. Indeed, prediction isn't divorced from power and, invariably, is jaundiced by prejudice. The utopias of the past often horrify us today. This insight is essential as we ourselves look forward.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThrough remaining always vigilant of this, however, we can foster openness and multiplicity. Indeed, expectations and designs on the future wouldn't become more reliable and inclusive, over time, if no one strove to be alert to their errors and exceptions in the here and now.

The tomorrows of 100 years ago prove all this, not just in their gregarious multiplicity, but also in the biases they preserve for us to learn from today. Taken together, the lesson perhaps is this: none of today's own tomorrows will truly stand time's test, but this is no bad thing. After all, if our present also remains corrupt – in ways both visible and currently invisible – it's perhaps not so terrible if tomorrow remains beyond our reach. What we aspire to be, but are ultimately not, should comfort us, for it means there's room for improvement beyond what we can currently muster.

Here lies the power of writing future histories like Brittain's, approached with playful irreverence to one's present. It coaxes us to dislodge the blinkers of the now, even if only performatively so: to goad ourselves, from the feigned perspective of centuries hence, for being the hostages to the status quo we no doubt will be revealed to have been. Perhaps, this way, we can reach for futures not only imagined today, but also those lying just beyond the borderlands of what's currently imaginable.

This is how prophesy – done right – can do more than reflect our own prejudices and preferences back to us. It can help reengineer them anew, provoking us to fumble for what might've been overlooked, pushing us in new and challenging directions, by forcing us to glimpse ourselves as the hidebound ancestors of tomorrow's alien world. It pays to remind ourselves that, just as with generations past, we are probably also prisoners to our parochial beliefs about what's most inevitable or inescapable about our present paradigm: beliefs which, in the fullness of time, are often proven mistaken.

Today, we excel in ill-fated dystopian visions, but in the past 100 years, have we lost some of the hopefulness of yesterday's tomorrows?

A century ago, hope remained prevalent. Perhaps after the traumas of the trenches, people couldn't help but imagine better tomorrows, to make recovery worthwhile. Today something similar applies again. Climate collapse very well could wreck Earth's future; but, because of this, we must hope for better worlds tomorrow.

Such hope is distinct from the techno-optimism that naively holds that, with enough unbridled innovation, "progress" becomes unstoppable and everything will inevitably go well. Instead, by clutching to the mere conviction that things can get better, hope acts as a lodestar – always shepherding but perpetually beyond reach. It steers all present attempts to move beyond our troubled present, fomenting every effort to fix what is wrong with the world right here and now, without demanding some impossible utopian perfection be imminently made manifest.

There are grave threats in our collective future, but let's not forget that approaching it with buoyant openness, as much as sombre gravity, can shift things towards what's better. After all, as Brittain's case illustrates, sometimes the truly tectonic social reforms are uttered first as semi-serious daydreams of "could" before they can become palpable matters of "must".

*Thomas Moynihan is a historian of ideas and author of X-Risk: How Humanity Discovered Its Own Extinction (MIT Press, 2020). Currently, he is a Visting Researcher at Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. He tweets at @nemocentric and can be found at thomasmoynihan.xyz.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.