Moments of hope and resilience from the climate frontlines

Riikka Morottaja

Riikka MorottajaFrom newborns saved by clean local power to the welcome return of an iconic lizard, our global reporters take stock of their most powerful moments in climate change of 2023.

The change is happening so rapidly that even the time between major climate reports can be measured in tenths of a degree of warming. Between one landmark report by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2018 and another in 2023, humans warmed the world by about 0.1C.

Taking stock of climate change can be difficult in a year of such rapid transformation as 2023.

How much have we heated the world?

Taking the surface temperature of an entire planet is no easy task.

In any given year, variable natural events cause fluctuations in the temperature – such as El Niño and volcanic eruptions. Scientists use modelling to tune out this natural noise to measure the warming that is caused by human activity.

In 2022, human-induced warming surpassed 1.25C for the first time. The year 2023 was even hotter. If you take an average over a decade – a measure used in the IPCC's sixth assessment report – the figure for human-induced warming between 2013 and 2022 was 1.14C.

"The current level of warming is 1.25C, and it's warming at a quarter of a degree per decade," says Myles Allen, professor of geosystem science at the University of Oxford in the UK, and a coordinating lead author on the IPCC's 2018 special report on 1.5C warming.

"You don't need a model to know that, if you are that close, we're going to reach 1.5C in around a decade or so at that rate of warming," says Allen.

These numbers can feel very abstract at times. What's not abstract is the effects of climate change as it laps at the thresholds of low-lying homes, burns buildings in climate-fuelled wildfires and thaws the permafrost beneath the feet of communities in the far north.

Future Planet's team of climate reporters write from across five continents to describe what they witnessed as the world warmed in 2023.

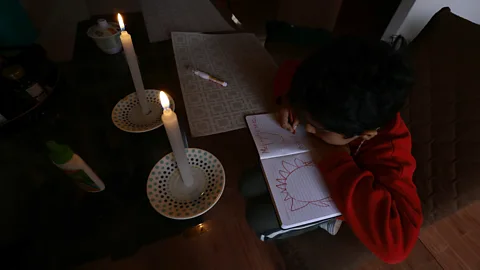

Mickal Aranha, Quito, Ecuador

In September, Ecuador raised its alert system from yellow to orange in preparation for El Niño. By October, it had arrived.

This year's El Niño has caused Ecuador's most severe drought in 50 years, which has affected production at hydroelectric plants. As a result, my family in Quito and people throughout Ecuador have been experiencing rolling blackouts that may continue into next year. The blackouts last three hours a day between 7am and 6pm, disrupting work, home life, causing traffic chaos, and heightening security problems in the country, which has been plagued by violence in recent years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSign up to Future Earth

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers. In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

The peak of this El Niño still looms. Intense rains are expected between December and February, which have historically led to floods and landslides on the coast and the Western Andes region, causing massive damage to infrastructure like roads and bridges.

This could impact food security, water quality, and health – floods are known to fuel a surge of mosquito-borne diseases like dengue. Farmers and the fishing community, meanwhile, are preparing for the loss of livelihood as floods sweep away their cacao and banana crops and El Niño's warming effect causes fish to migrate.

Ana Ionova, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

In Brazil, the climate crisis felt more real than ever this year. I've covered a steady stream of environmental disasters in recent years, from the razing of the Amazon rainforest to the wildfires in the Pantanal wetlands.

But in 2023, things felt different. It seemed like there was no respite from climate-induced tragedy here; for the first time, it was everywhere, all at once.

A historic drought parched the Amazon rainforest, drying up rivers and stranding people in remote villages with no food, water or medicine. Endangered pink dolphins died from heat stress in lakes, while smoke from wildfires choked whole cities. In southern Brazil, cyclones swept away neighbourhoods, killing dozens.

And in Rio de Janeiro, where I live, the death of a young concert-goer during yet another punishing heat wave put into sharp focus how a rapidly warming climate is changing every aspect of our lives.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmy Li Baksh, San Juan, Trinidad and Tobago

As a child, visiting nature reserves in the hills of Trinidad and Tobago, I was fascinated with the teeming wildlife. Hummingbirds, bats, agouti, dragonflies – the highlight would be spotting the lumbering Matte lizard, also known as the golden tegu.

But in recent years, the Matte, one of the largest lizards found on our twin islands, has been no longer as easy to spot. To find out why, I spoke to Kemba Jaramogi, whose family developed the Fondes Amandes Community Reforestation Project to fight forest fires, help reforestation, and teach other communities indigenous methods of living with the land.

"A Matte doesn't climb trees," says Jaramogi. "If the ground is continuously burnt, their home is at risk."

Repeated bushfires this year drove the lizards from their habitat in the leaf litter of the forest. The community project's work has helped the land recover enough that these majestic lizards are now returning to the spaces they once fled. To Jaramogi's excitement, she has recently spotted Mattes returning to the area.

It is just one example of how indigenous and communal knowledge give the Caribbean tools to protect and rehabilitate our home in the face of climate change.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLucy Sherriff, Los Angeles, United States

When I look over the stories I've written this year, the majority have been about how extreme weather is getting worse in the US, and how the country's response is woefully lacking. I live in LA, and friends of mine haven't gone out some days because the pollution has been so bad – and we didn't even have major wildfires this year.

In December, we've had days that have hit almost 30C (86F). We've celebrated when the rains have come because we're usually in a permanent state of drought. It's a running joke in California that we're always battling something – fire, floods, drought, or bracing ourselves for an earthquake.

This year has been a year of extreme weather anomalies. We have had a lot of rain – floods evacuated communities and washed out roads – but California's infrastructure isn't built to cope with it, so we couldn't bank the water. An entire lake refilled, swallowing whole farms, but bringing joy to the tribes who consider it sacred. Monumental snowfall resulted in entire towns being trapped inside their homes for days. An extreme heatwave saw temperatures reach 53C (127F).

The state is grappling with a new normality. And I don't think anyone is ready.

Saidu Bah, Freetown, Sierra Leone

It was eye-opening reporting for Future Planet's Climate Guardians series on the climate threats faced by women living in Sierra Leone's capital Freetown.

Many of the women living and working in Freetown's sprawling slums and street markets complained about the impact of extreme heat on their wellbeing and ability to work this year.

In previous years, "we were worried about fire disasters, flooding, mudslides and rising sea levels but now it's the changes in the weather patterns that is troubling us", Mariama Bangura, a 45-year-old resident of Kroobay slum, told me. "Extreme heat during the dry season is a silent killer. You can feel the impact without seeing it."

Ninety-four percent of Freetown's residents say the city was hotter in 2022 than it was five years ago. Women living in slum houses made of heat-trapping corrugated metal sheets are among the most vulnerable to the scorching temperatures.

Freetown has appointed a heat officer, Eugenia Kargbo, to help its residents cope with the temperatures. Her first moves have been installing shade covers to protect market vendors, and reflective roofs on slum dwellings, and planting one million trees across the city – an initiative that was nominated for the prestigious Earth Shot Prize in 2023.

Meer

MeerNalova Akua, Yaounde, Cameroon

Along the 470km (290 miles) of Cameroon's Atlantic Coast, erosion is one of the most pressing environmental concerns. In coastal towns like Bamusso, Ngosso and Kribi, and larger cities like Douala and Limbe, local communities are using sand bags, wooden fences and logs in an attempt to break the waves. The mangrove forests that have helped protect the region in the past are close to being overwhelmed.

"The beach that used to be over 100m [330ft] away from the highway 30 years ago is now threatening the tar on the road," says Isaac Njilah Konfor, a professor of earth sciences at the University of Yaoundé, Cameroon, who is researching the impact of sea level rise in the region. "The waves are becoming bigger and stronger."

Globally, the causes of coastal erosion are complex, including coastal development, but rising sea levels and storm surges due to climate change can add to the pressure.

Erika Benke, Lapland, Finland

While reporting in Lapland, I met Anna Morottaja, a fisherwoman and musician living in Inari, northern Finland. She says she has seen new species of birds and insects appearing in Lapland in recent years.

"I never saw greenfinches and blue tits in my childhood," she says. "They were common in central Finland, 800-900km (497-559 miles) to the south. Now they're here. Some came 10 years ago, some a year ago."

Riikka Morottaja

Riikka MorottajaLike most people living in Lapland, Morottaja uses a lot of firewood to heat her house and sauna. She chops up wood and stacks it in the yard in the winter, leaving the pile to dry by the end of the summer.

But she says the air has become a lot more humid and firewood now doesn't dry properly.

"When you make a fire, there's a lot of smoke and sizzle. Wood also gets mouldy when you put it in a pile," she says. "I used to store a small amount of firewood in the house but I have stopped doing it now: I don't want to introduce mould in the air that I breathe in."

To tackle the problem, Morottaja tells me that has had to build a new shelter with a roof to better protect her firewood from humidity. "Now we have a longer cycle. It takes two years rather than just one to dry firewood. So I need two shelters for wood. One is not enough."

Vandana K, Meghalaya, India

On a very rainy day, staff at the Mawtawar health clinic in Meghalaya in north-eastern India delivered a baby who couldn't breathe, move or cry. In a state where high demand is placed on too little hydroelectric power and power cuts are frequent, this might have been a hopeless situation for the young one's family.

But the health clinic staff used an oxygen concentrator powered by solar panels to increase the baby's oxygen levels in less than an hour. The baby now visits the clinic regularly with his mother to get immunised.

Health workers Bandashisha Diengdoh and Eva Kordor Marngar told me about the difference the recently installed solar panels have made to local healthcare, when I visited in September.

Now, a growing number of the state's 643 health facilities have access to solar power, after an effort by the government and the non-profit Selco Foundation that began in 2020. As I saw in Meghalaya, the switch to local, renewable sources of energy is already saving lives.

Kanika Gupta, Ladakh, India

Seventy-year-old Kungaga Norphel has seen a lot change in Ladakh in his lifetime. Norphel, who lives in Nang, a village in Ladakh in the Himalayas, says it doesn't rain or snow when it's supposed to anymore.

"There was very little snow this year," he told me when I visited in late November. "You can see yourself." As little as seven to 10 years ago, it would have snowed by now and the streams would be frozen, he says. "But this year, they are still flowing."

Norphel says the community has started collecting water from local ponds to make up for the lack of precipitation.

"We have four ponds in our village. Every year our village leader nominates four people who take turns to go up to the pond and fill it up with water from the nearby streams. After 6pm these men close the drain outlet in the pond so that it can fill up overnight. Then in the morning they make another trip to the pond to release the water. This water is enough for us to irrigate our fields," he says.

However, this method also poses risks, Norphel says. "Sometimes when it rains, we also have to go to [drain] the pond in the middle of the night to ensure that it doesn't overflow and flood the village."

Ringzen Wangyal, a local resident in Nang village, agrees that Ladakh has changed a lot over the years. "There are apples and apricots in the summer that we had never seen before," Wangyal says. The lack of rainfall means farmers now rely on water provided by the government to grow these crops.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesXiaoying You, London, UK (reporting on China)

I filed nearly 60 climate reports in 2023, and my most memorable exchanges were with Yu Kongjian, a leading Chinese landscape architect.

Yu, who narrowly avoided getting swept away by floods as a boy by grabbing onto a willow tree branch, is a big supporter of using nature-based solutions to tackle urban flooding, which has become more frequent in China. He is the innovator behind the "sponge city" concept, which proposes that nature can act as a giant sponge to absorb flood water and channel it under the ground.

He also often looks to the past for inspiration. We need to "think globally but act locally," he told me earlier this year, referring to the historic region of Huizhou in eastern China as an example. Here, every family used to manage rainwater by collecting and redirecting it. Huizhou was a home to plenty of ancient sustainability solutions, including ancient skywells that help keep homes cool.

As the world races to keep below the 1.5C threshold of warming, this year I've been thinking about the benefits of pausing to think about what we can learn from our past, simpler lifestyles.

--

Commissioning and editing by India Bourke, Isabelle Gerretsen, Richard Gray, Martha Henriques and Lucy Sherriff.

This article was updated on 03/01/2024 to clarify that Xiaoying You was reporting from London and that Huizhou was a historic region.

--