Red Sea cargo ship hijack: How to keep merchant vessels safe from attack

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA growing number of cargo vessels have come under attack in the Red Sea in recent weeks – can new technologies help to keep commercial shipping safe?

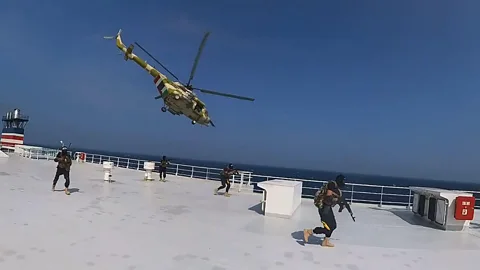

The gunmen arrive seemingly out of nowhere, descending from a clear blue sky. Their helicopter swoops down towards a 190m-long (623ft) merchant ship in the Red Sea, a key waterway between the Arabian Peninsula and north-east Africa. As the aircraft touches down on the upper deck, masked attackers swarm out.

They're wearing black and khaki gear, aiming their machine guns along the deck as they pace towards the ship's bridge. Once they reach it, there's shouting, they point their weapons at the crew, who surrender with their arms aloft. This is a hijacking.

Iran-backed Houthi rebels took control of the Galaxy Leader, a car carrier, in the Red Sea at the end of November. It is one of the most serious maritime security incidents of recent years and is one example of escalating military activity in the Red Sea, associated with the Israel-Gaza war. The Houthis made sure to capture their hijacking on video, for public dissemination. The Galaxy Leader's crew, all 25 of them, remain captive while the vessel itself is anchored outside the port of Hodeidah in Yemen.

Since this incident, there have been several other attacks on merchant vessels in the Red Sea, with a Norwegian tanker – the MT Strinda – hit by a missile, and other ships in the area have reported being fired upon by armed men in speedboats.

People have long puzzled over how to secure merchant vessels against threats of violence – especially more common forms of attack, in which assailants use a small boat or boats to approach commercial ships rather than helicopters. Somali pirates became notorious for doing this in the early 2000s and a wide range of lethal and non-lethal weapons systems were deployed against them. What happened to all those gadgets? And are they of any use today, to ships sailing the world's most dangerous seas?

"It's a multi-pitched, very high frequency tone. Very loud," says Richard Danforth, chief executive of Genasys, a US-based tech company. "It'll make you want to cover your ears."

He is describing the capabilities of his firm's long range acoustic devices, known as LRADs, which Genasys – formerly the American Technology Corporation – introduced in the early 2000s. Danforth says the idea of an LRAD is to either allow for long-range communication of verbal warnings to suspects, or for broadcasting an unpleasant, disorienting tone at high volumes.

Some early LRAD devices were capable of hurling sound across a stretch of water at targets nearly 500m (1,640ft) away. Genasys claims its models are now capable of projecting sound up to 3,000m (9,843ft) while automatically tracking the target.

The company claims that their system can work even if assailants wear ear protection. "Because much of human hearing is processed from the vibration of the small bones in your face and jaw, earplugs or headphones do little to reduce LRAD's effects," a spokesman says.

Danforth adds that some large commercial vessels, including container ships, are currently sailing with LRAD systems installed. Some of these are set up so that crew members can remotely control them from the bridge – to aim them, for instance, at a boatload of incoming pirates. LRADs are also used by the US Navy, some nuclear power plants, wealthy yacht owners and one system is even in place at the Hoover Dam on the Colorado River, according to Danforth.

But reports in 2008 suggested that an LRAD system was ineffective when Somali pirates hijacked the MV Biscaglia, a chemical tanker, although Genasys says the LRAD was never deployed during the incident. The security team defending the ship was forced to jump overboard. Separately, the crew of a cruise ship in 2005 reported successfully using LRAD and other techniques to fend off Somali pirates after the vessel was attacked with rocket launchers.

Alamy

AlamyThe sonic weapon is also not indestructible. "We have had LRADs shot before," says Danforth, as he describes a case in which police used one of the devices to communicate with an armed suspect holed up in a building. "The assailant opened the door and shot the LRAD," recalls Danforth. "It was no longer functional after that."

LRAD is just one tool at ship owners' disposal at a time when some of the world's most important waterways have become extremely dangerous for shipping. The war in Ukraine means that commercial ships in the Black Sea are also at risk of attack while the conflict in Gaza has led to a growing number of attacks by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea.

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) also stresses that, while Somali piracy is much less common today, it is not a completely neutralised threat. And there are still cases of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, for example, and the Singapore Strait. The boarding of vessels in the Singapore Strait in particular, one of the most congested waterways in the world, raises the risk of dangerous collisions involving large commercial ships, an IMB spokesman says.

Ship owners looking for ways to make their vessels more secure have access to a handy guide, however. It's called the BMP [Best Management Practices] 5 and is the work of a plethora of shipping industry organisations. In the "Ship Protection Measures" section, there is advice on hardening doors and windows, for instance, and making sure that you can see what's going on around the ship from the bridge.

That's not all, though. "Consider placing well-constructed dummies at strategic locations around the ship to give the impression of greater numbers of crew on watch," the dossier suggests. There's also mention of razor wire and various barrier systems to stop attackers climbing on board. One helpful note explains how you can prevent explosive devices from damaging the bridge: "Chain link fencing can be used to reduce the effects of an RPG (rocket propelled grenade)."

A number of technologies developed as ways of keeping ship-attackers at bay have, however, fallen by the wayside – at least in the merchant shipping domain. BAE Systems came up with a laser-based device that could be used to warn pirates up to 2,000m (1.2 miles) away to keep clear, or to dazzle them at closer ranges. A company spokesman says that, although the firm trialled this technology for anti-piracy applications in the past, no such BAE products are deployed on merchant vessels at present.

Another company, QinetiQ, helped to develop a special net that could be launched from a helicopter at incoming attacking boats. In theory, the net would wrap around the propeller and disable the craft. However, QinetiQ confirmed to the BBC that the system is no longer available for merchant shipping.

Water cannons are another strategy that have seen some use. At the height of the Somali piracy crisis, Swedish firm Unifire AB marketed its high-pressure nozzles as a solution. The company appears to no longer market them for such applications and a spokesman declined to comment for this article. But videos uploaded to YouTube about 12 years ago, with rock guitar soundtracks and captions such as "MASSIVE impact", suggested that Unifire's devices could be fixed to the side of large commercial vessels and pointed at hostile boats. With a range of up to 90m (300ft), the hoses were capable of firing up to 5,000 litres (1,099 gallons) of water per minute.

Former sea captain Tim Nease developed a water-based defence system at his previous company, International Maritime Security Network. The design involved large firehoses, which would produce flailing jets of water down the side of giant ships. "You could create a curtain around the ship that they couldn't get through," says Nease, explaining the potential impact on attackers approaching from sea-level.

Although water cannons have been used against pirates in the past, Shaun Robertson at EOS Risk Group, a security management company, is sceptical that such devices would work against heavily armed, highly determined assailants. "If you've got rocket propelled grenades and AK-47s maybe a water jet isn't going to deter you," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne of the, arguably, wackier ideas that surfaced at the height of the Somali piracy crisis was to spray attackers with unpleasant chemicals. Years ago, Nease asked a company in the US to come up with such a substance. He says it would not have caused permanent injury but was "nasty" stuff that had a bright fluorescent yellow colour.

"I'm going to tell you, if it gets on you, you're done, you're not shooting anybody," he says. "It was better than pepper spray."

BBC journalist Daniel Nasaw observed trials of the fluid in 2011 and had the opportunity to sniff a jug of it proffered by Nease. "Oh god, it's burning my nose," exclaimed Nasaw, recoiling. More than a decade later, Nease confirms the mixture was never deployed during a real security incident at sea. He now provides security training for vessel owners at Sea School, a maritime training facility in Florida.

"The thing that stopped piracy was armed guards on board," says Chris Long, intelligence director at Neptune P2P Group, a maritime security company. "Pirates didn't want to get killed, they just wanted money and if they got shot at, they would go away."

Neptune P2P Group offers armed security contingents to commercial vessel operators, though demand has fallen sharply in the last year or two, says Long. At one time, ship owners would pay £60,000 ($76,200) for a three-person British team but other countries now provide similar solutions for a fraction of this price, he explains.

Even with such on-board protection, in a situation where heavily armed state-backed or politically motivated attackers, such as the Houthis, were to board a vessel, a security team would probably not be able to engage them, says Long.

"We're not able, not mandated, if you like, to get involved in any state-actor attack," he explains. "If, for example, the Houthis tried to get on board, our guards would put their weapons down and let them."

Robertson agrees with this approach, noting, for one thing, the legal implications. "If they were to shoot a Houthi that was boarding a vessel, all hell would break loose," he says.

Alamy

AlamyWhen the threat goes beyond a small boatload of gun-toting pirates, it's nearly impossible for a merchant ship to defend itself, says Jakob Larsen, head of maritime safety and security at the ship owners' association Bimco. Attacks by highly capable military teams, missiles, and explosive-laden drones are too sophisticated to brush off. You can't put anti-aircraft or anti-missile systems on merchant vessels either, he stresses: "Weapons like that are simply not available to commercial shipping."

One option that is available to the crew of a vessel that comes under heavy attack is to retreat to the "citadel" – a secure room or chamber somewhere on the ship. These are usually hardened panic room-style facilities, says Larsen, with communications to the outside world and perhaps even limited controls for ship itself. This strategy risks antagonising a hijacking force, though, he adds.

But some anti-piracy measures can be effective against lesser-equipped aggressors, says Larsen. He recalls his previous role at shipping giant Maersk. "We experienced a couple of attacks off Nigeria," he says. "They were actually fought off by physical barriers and [by] increasing speed."

Maersk did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

One of the few options available that can really help keep merchant ships safe from heightened threats is naval protection. The US military is, at the time of writing, considering escorting commercial ships in the area of the Red Sea that could be at risk of attack while the US Navy has recently shot down three drones in self-defence, according to US Central Command. A French frigate also intercepted two drones in the area, the French military said. Larsen says Bimco welcomes all naval assets that can be deployed in defence of commercial shipping.

And Robertson points out that, without support like this, commercial vessels may be highly vulnerable. "They are kind of sitting ducks, in a sense," he says.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.