The daredevil flight to save rare birds

Waldrappteam

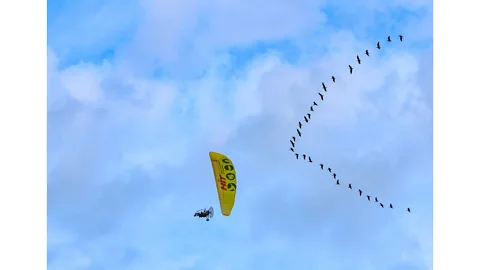

WaldrappteamStorms, an eagle attack, emergency landings, and a unique bond: how scientists led a flight of endangered ibises on a 2,300km journey to their new winter sanctuary.

It was mid-August, and Barbara Steininger, an Austrian biologist, was sitting in a rattling ultralight aircraft, flying across southern Germany. To her far left she could see a second aircraft and in it her colleague, Helena Wehner, a German geographer. Between them, flying in a perfect V formation, were 35 bald ibises: large, black, striking-looking birds with long beaks and halo-like tufts of feathers. They had been raised by the women as part of a conservation project, and would follow them anywhere. Right now, they were off on a 2,300km-journey (1,430 miles) to Spain, to a new winter camp, after their old one in Italy became inaccessible due to climate change.

"I really felt like, ok, the whole family is in flight, all of us are in the air. The birds are ready, and we are ready," says Steininger. It was her first time in flight with a flock of bald ibises, one of the world's rarest birds.

Human-led flights are at the core of the Waldrappteam project (Waldrapp is German for northern bald ibis), a conservation initiative that brought back the bird after it was hunted into extinction in Europe some 400 years ago. Over the past two decades, team members have led 15 flights of human-reared bald ibises from their summertime breeding sites in Austria and Germany across the Alps to wintering grounds in Italy, replenishing the recovering wild population. The community has grown to more than 200 from zero, and is judged on track to become a self-sustaining population, with older birds now migrating back and forth independently. Studies suggest that the seasonal journeys are crucial for the species' long-term survival since they allow them to breed in the food-rich northern Alpine foothills, while avoiding the harsh Alpine winters.

However, there is a new threat, says the project's founder and leader, Austrian biologist Johannes Fritz. Due to warmer autumns, bald ibises who have learned the route to Italy are starting their journey south later and later in the year, according to the team's 2022 annual report. Their late departure means they now reach the high Alpine passes in late October or November, compared to early October in the past. By then, the passes are frozen, and the air is too cold to allow them to fly over them, using thermal uplift. Last year, 29 of them were stuck in the snow and had to be captured and driven across the Alps to the southern side, where they resumed their migration. Remaining on the northern side puts them at risk of freezing to death.

"We've just saved the bald ibis, and now it's threatened with extinction by climate change. The birds are stuck north of the Alps," says Fritz, who is also one of the project's pilots.

This year, the team decided to show a newly reared group a route that avoided the frozen Alpine passes, and instead, took the birds westwards, through southern Germany, France and then across the Pyrenees, to Spain. On this route, the birds are less reliant on thermal uplift as the mountains are lower, Wehner says. The two aircraft were flown by Fritz and a professional pilot, Walter Holzmüller, with Wehner and Steininger sitting behind them. Over the course of six weeks, they confronted storms, emergency landings, a bird of prey attack, and a rogue paraglider. Here are some of their most dramatic moments – and what they can teach us about helping birds migrate in a changing world.

Waldrappteam

WaldrappteamEarly April: Becoming a family

Helena Wehner, Barbara Steininger and Laura Pahnke, the project's camp leader and a trained vet, are brainstorming baby names for 35 newly hatched bald ibises. The chicks are supplied by a zoo in Austria that keeps free-flying bald ibises, which produce more offspring than they could raise. The next day, Wehner and Steininger officially start their roles as foster parents to the chicks – and from then on, spend every waking moment with them.

"As a foster mother, it's really important to enjoy caring for these young birds, and to let yourself become a part of the birds' world," says Wehner, who raised and led three previous cohorts. Only if the birds fully accept and trust them as mothers, a process known as imprinting, will they follow them in flight, she and Steininger say. The scientists even put their faces in the chicks' nests, to let them explore their features. Later, the grown birds still like to probe their nostrils with their curved beaks.

"We really start behaving a bit like birds over time, because we look at our environment in a totally different way [compared to humans]," says Steininger. This also means supporting the ibises in learning about threats, such as birds of prey, whenever they sit outside together. "When a red kite passes over us, we all stop talking and go really quiet, and all of us look up. And those are exactly the things the birds need to know later on, in the wild," she adds. Instinctively, Wehner and Steininger have taken on the habit of looking up as a bald ibis does: head cocked, one eye on the sky.

The intense bonding phase also allows the scientists to get to know each bird's personality, which matters for flying together. "As chicks, some already seek more contact and those are then often the ones who will fly along very eagerly," Wehner says. Others might be more mischievous, or particularly curious by nature. "And those are the ones who might fall behind the rest of the group, because they're distracted by a dandelion with an exciting beetle on it."

Waldrappteam

WaldrappteamMay: Learning to fly

It's May, and the birds are in a mobile flight training camp in southern Germany, ready to fledge. "We don't coax them, they have to make this decision alone, just like in nature," says Steininger. This can take time: "The bald ibis breeds in rock faces. The young birds can sit there for days, peering down, until they finally dare to try and fly." It's a significant drop, often 10-20 metres [33-66ft]. "So they'd better flap their wings."

In the camp, an opening connects the birds' nest with an aviary. They hop and flutter up a ramp to the opening, and one by one, fly through. When all of them are ready, the scientists release the whole group from the aviary. They are not equipped with any GPS devices at this point, to allow them to make their first migratory flight unimpeded. "It's a magical moment, seeing all 35 of them in the air," says Steininger. "Although their flight is still a bit chaotic at this stage."

If left to their own devices now, these young ibises would feel an innate urge to migrate in the autumn. They would also have the innate ability to cover large distances, and fly in a V-shaped formation. But one crucial thing is not innate: knowing where to go.

"A lot of the bald ibis' migratory behaviour is genetically determined, but the route to their wintering grounds is a social tradition," says Fritz. "In the autumn of their first year of life, the juvenile birds need to follow someone – older, experienced bald ibises, usually – to reach their wintering grounds. And then they will store that location in their brain for the rest of their lives." How exactly they and other migrating birds do that is still a matter of scientific debate – they may use a number of aids, including the Earth's magnetic field.

In the 1990s, before the human-led flights, bald ibises from a zoo in Austria tragically showed what happens when there is no one to teach them a safe migration route. The birds were raised by humans as part of a reintroduction project and allowed to fly freely. They thrived in the wild, and when autumn came, followed their innate urge to leave. But with no experienced elders to show them, they flew in random directions and ended up all over Europe, including in even more northern countries with bitterly cold winters, where they froze to death, Fritz says. Inspired by a popular Hollywood movie, "Fly Away Home", about a girl leading geese on a migration, Fritz and his team began leading young bald ibises to Italy, using aircraft.

After their first trip, the bald ibises not only know the way, they can even improve it. For example, past human-led flights from Germany to Italy had to bypass Switzerland due to flight regulations, Fritz says; but when adult bald ibises fly back independently they just take the most direct route, straight through Switzerland.

Waldrappteam

WaldrappteamAugust 21: Leaving home

The big day has arrived: the whole formation is up in the air, heading for Spain. They will spend each night in a camp, the birds in a mobile aviary, the humans in tents.

The birds have become used to the aircraft, taken many practice flights, and are closely bonded with their foster mothers. Still, it's an effort to keep everyone together, the researchers say. Wehner and Steininger each hold a megaphone, calling "Come, come, Waldi, come, come!" to the birds.

Their V-shaped formation helps them save energy, Wehner says, as each bird is pulled along by the updraught created by the flapping wings of the bird in front. It's also easier to lead them when they fly this way. Their other favoured, innate strategy for long-distance flights involves circling in a column of rising warm air, using the thermal updraft to gain height, then gliding across the sky. This saves even more energy – but, Wehner says, it makes it harder to keep sight of the birds, and lead them. That day, the flight goes well, and they arrive at their overnight camp as planned.

Late August: A deadly threat

As the group fly into France, they encounter their first major obstacle: a nuclear power plant, surrounded by a maze of power lines.

"Electrocution is the biggest threat to the bald ibis," Wehner says. It is by far the most common cause of death of them in Europe. The team is working with power companies to secure high-risk masts. They also fight against another major threat to the birds: illegal hunting in Italy. "Illegal hunting and electrocution are two areas where we don't just protect the bald ibis, we also simultaneously protect other bird species [through our work]," says Wehner.

End-August: Finding Waldi

Disaster strikes: on a flight through mountainous territory in France, about half the birds split off and vanish from sight. The team tries to find them, while also keeping the rest of the group together. Eventually, they decide to land with the remaining 18 birds. Wehner stays with them, and Steininger and camp leader Pahnke continue the search.

"We said, 'We're not giving up, we're going try everything we can to find them,'" Steininger says. "The French public were a huge help – nothing is more helpful than people getting in touch with sightings."

They follow every clue, driving for hours, and Steininger keeps calling out for the birds. "I don't think I've ever called that much in my life." They find most of them, also helped by the fact that the birds tend to fly back to the last stopover. But after a week, seven are still missing.

Waldrappteam

WaldrappteamEarly September: Fellow travellers

To avoid losing time, and make use of good weather conditions, Wehner flies ahead with the remaining bald ibises. As they rest near the Spanish border, she looks up and sees something that lifts her spirits: several hundred storks, circling in a thermal updraught. They are travelling along the same migratory route as the bald ibises, from Central Europe to southern Spain – but the storks will then continue, all the way to Africa.

"We really felt part of this worldwide migration, because we were on a route where many, many birds migrate," says Wehner. "And we were crossing our fingers for all of them, and willing them to succeed."

Just as they are about to lose hope, Steininger and Pahnke find the missing birds, sitting on a meadow. "They were all in a very good state of health, which showed that they can survive without us now," says Steininger – though they still need to be guided to find their way south. They drive the birds to the other group. Such short interruptions don't threaten the birds' ability to learn the overall route, Fritz says, as long as most of the way is covered in flight. Together, they resume the journey and fly over the Pyrenees, into Spain.

Mid-September: A beach flight – and an eagle attack

The birds see the sea for the first time, and the group enjoy a spectacular flight along a beach: "It was breathtakingly beautiful. I really noticed how much fun they were having," Steininger says. How does one tell when a bald ibis is having fun? They fly fast, Steininger says, and "they change sides, and look at the scenery, and really enjoy themselves".

However, there is another dramatic twist: as they veer inland and fly through a mountainous area, the flock suddenly scatters. The scientists lose sight of 27 birds. They fear that something frightened them, a raptor perhaps. Later, Spanish locals report that they saw a bird being chased by an eagle. Twenty-five of the bald ibises are found and reunited with the group, but two remain missing.

Simple tricks to help migrating birds

All of us can help migrating birds, Wehner says, by doing one simple thing: picking up litter, or even better, avoiding littering in the first place. Litter can be very dangerous for birds when mistaken for food and swallowed.

Reducing light pollution can also help keep birds safe. In the US, the Lights Out campaign encourages people to switch off non-essential lighting during migration periods, to reduce deaths from collisions with buildings.

Waldrappteam

WaldrappteamEarly October: A Spanish welcome

Strong, unrelenting winds plague the group as they fly through southern Spain. Once, unable to find a safe landing strip amid olive groves, they make an emergency landing in an open sewer. It's the only suitable surface – and it is empty, thankfully. More emergency landings follow, and they lose another bird. At the start of October, after six weeks of flying, the pilots decide it is no longer safe to continue, due to the wind. They are about an hour's drive from San Ambrosio, their destination in Andalusia, southern Spain. There, a project called Proyecto Eremita has reintroduced a southern colony of wild bald ibises who live in the area year-round. Already, the new arrivals are in the home range of those wild bald ibises, and can be driven by car for the final stretch to San Ambrosio.

Wehner and Steininger notice a group of brown ibises – relatives of the bald ibis – who approach their birds with curiosity. "It was so nice to see the bird community receiving them warmly. And it was an emotional moment for us because we knew that the bald ibises were going to have a lovely home here, and interact with other species as well," Steininger says. They see wild bald ibises, too. "You feel as if you just led these birds to paradise, where they have wild relatives who live in freedom," she says.

In San Ambrosio, a welcome party greets them, with singing school children and revellers in bald iris costumes. The team fly one last round with the birds, to the crowd's delight. Then the slow process of letting go begins. Over the following days, the foster mothers spend less time with their birds, who are now old enough to naturally want to spend more time with their peers. Their special bond will last, however: whenever Wehner encounters Northern bald ibises from previous migrations, they still recognise her, greet her and fly to her, she says.

In about three years' time, the birds will fly back north to mate and breed, says Fritz. The hope is that eventually, they will merge with the Spanish colony and all migrate together to breeding grounds in the Alpine foothills. The birds usually fly faster in that direction, he says, as the first ones to reach the breeding grounds have the widest choice of partners and nesting sites.

For Wehner, the experience also offers a wider lesson: "I think this shows that whenever we have a chance to save a species, we should use it. It offers a glimmer of hope." She and Steininger are back home in Germany and Austria, respectively. But even now, they still instinctively glance up at the sky, with one eye, whenever flocks of birds pass overhead. "It's not a habit you shake off quickly," Wehner says. "You see the world more like a bird."

CARBON COUNT:

The emissions it took to report this story were 0kg of CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

--