Could we find alien life via its pollution?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlien life may one day be found not from radio signals beamed across the cosmos but from an all-too-familiar side-effect of civilisation: pollution.

It's the Earth's atmosphere that he's usually concerned with. But one day about 10 years ago, a colleague knocked on Gonzalo González Abad's door and asked him an unexpected question: "If you were looking for traces of a technologically advanced alien civilisation, light years away from us, how would you try to do it?"

This article is part of a week special coverage about aliens – all to mark the upcoming 60th Anniversary of the BBC's most famous alien lifeform, Doctor Who.

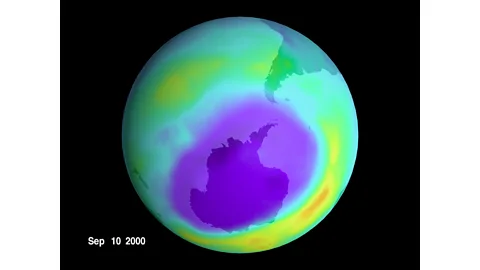

González Abad, an atmospheric scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, thought for a moment before replying, "CFCs" – chlorofluorocarbons. On Earth, various appliances including aerosol cans and fridges released these gases for years, in huge volumes, before we realised that CFCs were eroding the ozone layer.

"They last a long time – and, definitely, nature doesn't produce them," González Abad says. If some alien population had polluted their world the way we polluted ours in the 20th Century, telescopes might just be able to detect the presence of CFCs in their planet's atmosphere. It would be a hint, potentially, of a technology-rich culture elsewhere in the universe. What scientists call a "technosignature".

Perhaps we are not alone…in messing up a planet. Just like how people's rubbish can reveal their secrets, aliens could give themselves away through their sheer slovenliness. Over the years, researchers have thought about this quite a bit and they've come up with various possible technosignatures that rely on high levels of extraterrestrial pollution. From excessive light to space debris or harmful gases in the atmosphere of an alien planet, different kinds of detritus could in theory reveal the presence of a distant civilisation.

Now, telescopes powerful enough to detect technosignatures are emerging and many scientists hope to use them in the coming decades to try and find life on other worlds. The trash is out there. Maybe.

In 2014, González Abad co-authored a paper that discussed the possibility of finding aliens via CFC emissions. The researchers calculated that, if the concentration of these gases in the atmosphere of a distant planet reached roughly 10 times their concentration on Earth, it might be possible to detect their presence using the James Webb Space Telescope, which became operational in 2022.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCrucially, CFCs could remain in a planet's atmosphere for tens of thousands of years, meaning that an alien civilisation would not necessarily have to produce them for very long in order to leave a trace of CFC-related activity. The chlorine in Earth's atmosphere today is there due to the emission of CFCs in past decades. These gases are banned worldwide today, though there's plenty of work still to do if we are to eliminate them entirely.

Detection of CFCs with the James Webb Space Telescope might be possible if the polluted planet were orbiting a small white dwarf star, González Abad and his co-authors suggest, since that would increase the chances of useful levels of light reaching Earth. Scientists are able to look for CFCs, and various other chemicals in faraway planets' atmospheres, by studying the spectra – or specific wavelengths of light – reflected off alien worlds. Since some light is absorbed by chemicals while some passes through, the precise character of the onward light can reveal what chemicals are present on a distant body.

Many of the proposals for extraterrestrial technosignatures that have been floated to date are inspired by pollutants that humans have created here on Earth. Scientists have pondered whether we might find alien civilisations by spotting huge amounts of waste heat emitted by industrial sources, for instance. Others have suggested that, if aliens ever succumbed to a large-scale nuclear war on their planet, we might be able to see the bright flashes of their exploding warheads from Earth. And then there's space debris – could we spy masses of it orbiting another world? Perhaps some of it will drift by Earth one day.

Science fiction is full of stories of humans exploring space only to run in to alien detritus. In the 1979 film Alien, the crew of the Nostromo stumble on a crashed alien megaship. The less said about what happens next in that case, though, the better.

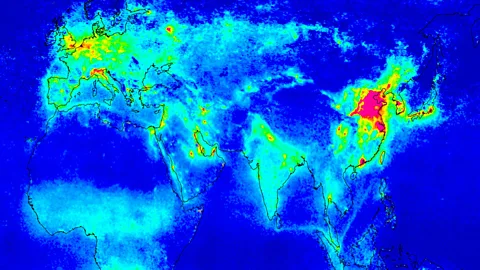

Returning to gases, which could be detectable from much further away, scientists have considered searching for other gaseous pollutants besides CFCs. Take nitrogen dioxide, or NO2. "Most of the NO2 on our planet comes from industrial activity," says Giada Arney of Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center, who co-authored a 2021 study on the potential for discovering alien civilisations by searching the galaxy for NO2 pollution. On Earth, about 65% of NO2 comes from emissions caused by cars, ships, planes and power plants, among other anthropogenic sources.

Unlike CFCs, NO2 doesn't hang around in the atmosphere for thousands of years, which could make it harder to find on other planets. However, on the flipside, the waxing and waning of NO2 concentrations could give us a clue as to the levels of industrial activity occurring on an alien world. Arney explains that she and her colleagues got the idea for their paper after NO2 levels in Earth's atmosphere fell sharply during Covid-19 lockdowns. Ground measurements revealed that NO2 plummeted by around 30% in some countries that had strict lockdowns – and reductions in NO2 emissions were also observed by satellites orbiting the Earth.

It's not unreasonable to suggest that an alien civilisation watching us might notice this change. "One might also think about temporal technosignatures that could give you additional information about what's going on in the planet's atmosphere," says Arney.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBesides the short life of NO2, however, there's also the issue that there are quite a lot of natural sources that produce it – from lightning to wildfires, so finding it might not be hard proof that an alien civilisation had developed internal combustion engines, for instance, or any other NO2-spewing technology. That said, Arney and her co-authors argue that, on Earth, natural sources would not on their own produce enough NO2 to make it detectable from afar. Therefore, observing it in the atmosphere of another planet might actually hint that industrial activity of some kind is afoot.

Scientists are already poring over the light reflected off distant planets to try and determine what chemicals might be present there. In September, researchers reported that they had used the James Webb Space Telescope to detect methane and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a planet called K2-18b, which orbits a dwarf star around 120 light years from Earth. This in itself was a major discovery as it suggests that the planet could be swathed by an ocean of water.

"This is the first time ever we have been able to come this close to saying that we can tell there is an ocean on an exoplanet," says Nikku Madhusudhan at the University of Cambridge.

You might also like:

But he and his colleagues also found evidence for an even more exciting compound known as dimethyl sulphide, or DMS, in K2-18b's atmosphere. On Earth, only life produces this compound, though it is also emitted by some industrial sources – pulping mills that process wood, for example.

Madhusudhan stresses that the result is tentative and requires further confirmation to be sure that DMS is really there. But, in principle, it could be a biosignature – a sign of life – and, who knows, perhaps even a technosignature, too, if aliens are processing materials similarly to how we process timber on Earth. Madhusudhan adds, however, that he finds it hard to imagine an industrialised alien civilisation on a world that may be entirely covered in water.

And yet, the search for life elsewhere in the universe should, he says, consider possibilities that would surprise us: "We ought to be expecting the unexpected."

The great strength of proposals to search for technologically advanced civilisations via pollutant gases is that, in the coming decades, our observational capabilities will improve drastically, says Jane Greaves of Cardiff University. "It's impressive that these trace gases are potentially detectable at all," she explains, noting that upcoming telescopes will be well-suited to this kind of analysis.

Besides the James Webb Space Telescope, which now orbits the sun, there's the European Southern Observatory's Extremely Large Telescope, a ground-based facility in Chile that is due to become operational in 2028. Nasa is currently planning a space-based telescope called the Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor, or Luvoir, for the 2030s. Arney and her colleagues considered the capabilities of this device this when calculating how they might detect NO2 on an alien planet. And finally there's the Habitable Worlds Observatory, a telescope specifically designed to hunt for biosignatures – and perhaps technosignatures, by extension – in the late 2030s or 2040s. "If we can hang on an annoying number of years, it's going to be fascinating," says Greaves.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut optical telescopes have their limitations. Andrew Siemion at the Seti Institute, which was set up to search for life elsewhere in the Universe, says that most of his organisation's efforts are directed towards detecting radio signals beamed across the galaxy by aliens.

"We spend maybe 5% of our time and reason on some of these other ideas," he says, noting that radio emissions could be detected "across the galaxy" meaning we might have a higher chance of spotting them.

Siemion makes another point. Since the possible technosignatures that have been suggested so far are essentially all based on pollutants that humans have produced, there's a risk that we assume alien civilisations will be highly similar to our own, when there's no guarantee that that would be the case. As Madhusudhan says, "expect the unexpected" – rather than taking an anthropocentric view of life across the Universe. With this in mind, Seti is increasingly focused on a search for anomalies in data rather than specific traces that we might assume could be left by an alien population, says Siemion. Anything that's weird in a dataset of cosmic observations could be the smoking gun we need.

"We don't have to get in the mind of ET, so to speak, and imagine what they might do or even demand that they have the same kind of technological evolution that human beings did," Siemion explains.

In other words, it's not necessary to even know what, exactly, we're looking for – we just have to find something unexpected that warrants further investigation.

Perhaps all of these proposed technosignatures, while potentially on the right track, are more of a reflection of our growing awareness that humans are a messy, polluting species. Maybe there's even some guilt bound up in there, too. We console ourselves by imagining that aliens would make the same mistakes.

As Arney says, truly intelligent lifeforms might not, in the end, produce pollutant-based technosignatures, even CFCs, for long stretches in their history – perhaps only for fleeting moments before they clean up their activities. If so, we would have to be lucky to be looking for such signatures at just the right time.

"I wonder a little bit as to how long pollution will express itself," says Arney. "I like to hope that a civilisation will get its act together."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.