How a dose of MDMA transformed a white supremacist

Getty Images

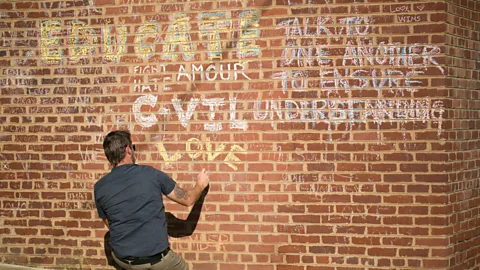

Getty ImagesBrendan was once a leader in the US white nationalist movement. But when he took the drug MDMA in a scientific study, it would radically change his extremist beliefs – to the surprise of everyone involved. Rachel Nuwer investigates what happened.

In February 2020, Harriet de Wit, a professor of psychiatry and behavioural science at the University of Chicago, was running an experiment on whether the drug MDMA increased the pleasantness of social touch in healthy volunteers. The day was proceeding like any other Tuesday when Mike Bremmer, de Wit's research assistant, appeared at her office door with a concerned look on his face.

The latest participant in the double-blind trial, a man named Brendan, had filled out a standard questionnaire at the end. Strangely, at the very bottom of the form, Brendan had written in bold letters: "This experience has helped me sort out a debilitating personal issue. Google my name. I now know what I need to do."

Seeing this cryptic message, both Bremmer and de Wit were worried. "We really have to look into this," de Wit said. They googled Brendan's name, and up popped a disturbing revelation: until just a couple of months before, Brendan had been the leader of the US Midwest faction of Identity Evropa, a notorious white nationalist group rebranded in 2019 as the American Identity Movement. Two months earlier, activists at Chicago Antifascist Action had exposed Brendan's identity, and he had lost his job.

De Wit was now very worried. She'd just given a drug to a disgraced white supremacist, she realised, and had apparently inspired him to do who knows what out in the world. "Go ask him what he means by 'I now know what I need to do,'" she instructed Bremmer. "If it's a matter of him picking up an automatic rifle or something, we have to intervene."

A murderous spree turned out to be the opposite of what Brendan had in mind. As he clarified to Bremmer, love is what he had just realised he had to do. "Love is the most important thing," he told the baffled research assistant. "Nothing matters without love."

When de Wit recounted this story to me nearly two years after the fact, she still could hardly believe it. "Isn't that amazing?" she said. "It's what everyone says about this damn drug, that it makes people feel love. To think that a drug could change somebody's beliefs and thoughts without any expectations – it's mind-boggling."

Over the past few years, I've been investigating the scientific research and medical potential of MDMA for a book called "I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World". I learnt how this once-vilified drug is now remerging as a therapeutic agent – a role it previously played in the 1970s and 1980s, prior to its criminalisation. If this comes to pass, MDMA – and other psychedelics-assisted therapy – could transform the field of mental health through widespread clinical use in the US and beyond, for addressing trauma and possibly other conditions as well, including substance use disorders, depression and eating disorders.

But could MDMA transform people's beliefs too? MDMA does not seem to be able to magically rid people of prejudice, bigotry, or hate on its own. But some researchers have begun to wonder if it could be an effective tool for pushing people who are already somehow primed to reconsider their ideology toward a new way of seeing things. While MDMA cannot fix societal-level drivers of prejudice and disconnection, on an individual basis it can make a difference. In certain cases, the drug may even be able to help people see through the fog of discrimination and fear that divides so many of us.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen De Wit told me the story about Brendan, I wanted to hear more about what happened directly from the horse's mouth, so in December 2021 I paid Brendan a visit (he asked that his last name not be revealed, as he's trying to distance himself from his past). As I rode the elevator up to his apartment in a luxury high-rise overlooking Lake Michigan, I felt a flutter of nervousness. I was unsure of what kind of person I would be meeting, and had even half-jokingly texted a couple of friends to let them know where to come looking for me in case I disappeared. What I didn't expect was how ordinary the 31-year-old who answered the door would appear to be: blue plaid button-up shirt, neatly cropped hair, and a friendly smile.

After politely hanging up my coat, he explained that, back when he was a white nationalist leader, cultivating an air of ordinariness had been exactly the point. "I really wanted it to be for guys making a good amount of money, who are educated and who could feel comfortable joining these sorts of communities," he said. "I wanted to normalise it."

Read more:

Brendan grew up in an affluent Chicago suburb in an Irish Catholic family. He leaned liberal in high school but got sucked into white nationalism at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he joined a fraternity mostly composed of conservative Republican men, began reading antisemitic conspiracy books, and fell down a rabbit hole of racist, sexist content online. Brendan was further emboldened by the populist rhetoric of Donald Trump during his presidential campaign. "His speech talking about Mexicans being rapists, the fixation on the border wall and deporting everyone, the Muslim ban – I didn't really get white nationalism until Trump started running for president," Brendan said.

Brendan joined Identity Evropa to connect with others who shared his views. He attended the notorious "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville and quickly rose up the ranks of his organisation, first becoming the coordinator for Illinois and then the entire Midwest. He travelled to Europe and around the US to meet other white nationalist groups, with the ultimate goal of taking the movement mainstream.

Brendan likely would have continued in this vein were it not for his identity becoming public. A group of anti-fascist activists published identifying information about him and more than 100 other people in Identity Evropa. He was immediately fired from his job and ostracised by his siblings and friends outside white nationalism.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Brendan saw a Facebook ad in early 2020 for some sort of drug trial at the University of Chicago, he decided to apply just to have something to do and to earn a little money. At one of the visits, he was given a pill. He didn't know it, but he'd just taken 110mg of MDMA. At the time, Brendan was "still in the denial stage" following his identity becoming public, he said. He was racked with regret – not over his bigoted views, which he still held, but over the missteps that had landed him in this predicament.

About 30 minutes after taking the pill, he started to feel peculiar. "Wait a second – why am I doing this? Why am I thinking this way?" he began to wonder. "Why did I ever think it was okay to jeopardise relationships with just about everyone in my life?"

Just then, Bremmer came to collect Brendan to start the experiment. Brendan slid into an MRI, and Bremmer started tickling his forearm with a brush and asked him to rate how pleasant it felt. "I noticed it was making me happier – the experience of the touch," Brendan recalled. "I started progressively rating it higher and higher." As he relished in the pleasurable feeling, a single, powerful word popped into his mind: connection.

It suddenly seemed so obvious: connections with other people were all that mattered. "This is stuff you can't really put into words, but it was so profound," Brendan said. "I conceived of my relationships with other people not as distinct boundaries with distinct entities, but more as we-are-all-one. I realised I'd been fixated on stuff that doesn't really matter, and is just so messed up, and that I'd been totally missing the point. I hadn't been soaking up the joy that life has to offer."

That night Brendan reached out to Chicago Antifascist Action and connected with the specific former activist there, "S", who had gone undercover in Identity Evropa before revealing Brendan's identity (S asked me not to reveal his name, to ensure he can continue his undercover work as an activist, although he is no longer affiliated with Chicago Antifascist Action.)

At first, S was sceptical when Brendan claimed that MDMA had made him want to prioritise connecting with other people above all else. But he was heartened when Brendan started taking steps that seemed to indicate his sincere commitment to change. Brendan hired a diversity, equity, and inclusion consultant to advise him, enrolled in therapy, began meditating, and started working his way through a list of educational books. S still regularly communicates with Brendan and, for his part, thinks that Brendan is serious in his efforts to change. "It's been a couple years we've been working together, trying to disconnect him from things that were harmful and reconnect him with positive reinforcement and get him ideologically educated," S told me. "I think he is trying to better himself and work on himself, and I do think that experience with MDMA had an impact on him. It's been a touchstone for growth, and over time, I think, the reflection on that experience has had a greater impact on him than necessarily the experience itself."

Brendan is still struggling, though, to make the connections with others that he craves. When I visited him, he'd just spent Thanksgiving alone. He also has not completely abandoned his bigoted ideology, and is not sure that will ever be possible. "There are moments when I have racist or antisemitic thoughts, definitely," he said. "But now I can recognise that those kinds of thought patterns are harming me more than anyone else."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile Brendan's experience is outside the norm, it's not without precedent. In the 1980s, for example, an acquaintance of early MDMA-assisted therapy practitioner Requa Greer administered the drug to a pilot who had grown up in a racist home and had inherited those views. The pilot had always accepted his bigoted way of thinking as being a normal, accurate reflection of the way things were. MDMA, however, "gave him a clear vision that unexamined racism was both wrong and mean," Greer says.

Rare as they might be, stories such as these are worth examining for the implications they give about MDMA's potential ability to "influence a person's values and priorities", as de Wit and several co-authors wrote in a case study they published about Brendan in 2021 in the journal Biological Psychiatry. If "extremist views [are] fueled by fear, anger and cognitive biases", the researchers posed, "might these be targets of pharmacological intervention"?

Encouraging stories of seemingly spontaneous change appear to be exceptions to the norm, however, and from a neurological point of view, this makes sense. Research shows that oxytocin – one of the key hormones that MDMA triggers neurons to release – drives a "tend and defend" response across the animal kingdom. The same oxytocin that causes a mother bear to nurture her newborn, for example, also fuels her rage when she perceives a threat to her cub. In people, oxytocin likewise strengthens caregiving tendencies toward liked members of a person's in-group and strangers perceived to belong to the same group, but it increases hostility toward individuals from disliked groups. In a 2010 study published in Science, for example, men who inhaled oxytocin were three times more likely to donate money to members of their team in an economic game, as well as more likely to harshly punish competing players for not donating enough. (Read more: "The surprising downsides of empathy.")

According to research published this week in Nature by Johns Hopkins University neuroscientist Gül Dölen, MDMA and other psychedelics – including psilocybin, LSD, ketamine and ibogaine – work therapeutically by reopening a critical period in the brain. Critical periods are finite windows of impressionability that typically occur in childhood, when our brains are more malleable and primed to learn new things. But Dölen and her colleagues' findings likewise indicate that, without the proper set and setting, MDMA and other psychedelics probably do not reopen critical periods, which means they will not have a spontaneous, revelatory effect for ridding someone of bigoted beliefs.

Anecdotally, some members of the Taliban, for example, use MDMA to channel a connection to the divine during prayer chants, according to a drug activist based in Kabul who I interviewed for my book. In the West, plenty of members of right-wing authoritarian political movements, including neo-Nazi groups, also have track records of taking MDMA and other psychedelics. This suggests, researchers write, that psychedelics are nonspecific, "politically pluripotent" amplifiers of whatever is going on in somebody's head, with no particular directional leaning "on the axes of conservatism-liberalism or authoritarianism-egalitarianism."

That said, a growing body of scientific evidence indicates that the human capacity for compassion, kindness, empathy, gratitude, altruism, fairness, trust, and cooperation are core features of our natures. If MDMA, with proper preparation, can nudge us toward embracing this state of being, then the idea of using the drug as an aid to help make the world a more loving, less hateful place may be more than just a pipe dream. As Emory University primatologist Frans de Waal wrote, "Empathy is the one weapon in the human repertoire that can rid us of the curse of xenophobia."

Alamy

AlamyNatalie Ginsberg, the global impact officer at the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (Maps) – a non-profit group that has been spearheading research on MDMA – remembers standing next to the Washington Monument in DC at the Catharsis Festival right after the 2016 election, talking with Maps’s founder Rick Doblin at 1:00 or 2:00 in the morning about the possibility of using MDMA to facilitate a dialogue between Republicans and Democrats. Ginsberg also envisions using the drug in workshops aimed at eliminating racism, or as a means of bringing people together from opposite sides of shared cultural histories to help heal intergenerational trauma. "I think all psychedelics have a role to play, but I think MDMA has a particularly key role because you're both expanded and present, heart-open and really able to listen in a new way," Ginsberg says. "That's something really powerful."

"If you give MDMA to hard-core haters on each side of an issue, I don't think it'll do a lot of good," Doblin adds. "But if you start with open-minded people on both sides, then I think it can work. You can improve communications and build empathy between groups, and help people be more capable of analysing the world from a more balanced perspective rather than from fear-based, anxiety-based distrust."

In 2021, Ginsberg and Doblin were coauthors on a study investigating the possibility of using ayahuasca – a plant-based psychedelic – in group contexts to bridge divides between Palestinians and Israelis, with positive findings. They hope to undertake a similar study using MDMA in the future.

MDMA is not going to end war, bigotry, and polarisation any more than it will permanently transform anti-social octopuses into social butterflies. But there could be a role for it and other psychedelics to play to help people better see each other as fellow human beings. "I kind of have a fantasy that maybe as we get more reacquainted with psychedelics, there could be group-based experiences that build community resiliency and are intentionally oriented toward breaking down barriers between people, having people see things from other perspectives and detribalising our society," says psychiatrist Franklin King at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. "But that's not going to happen on its own. It would have to be intentional, and – if it happens – it would probably take multiple generations."

Based on his experience with extremism, Brendan agreed with expert takes that no drug, on its own, will spontaneously change the minds of white supremacists or end political conflict in the US. "A lot of these guys who end up in these movements have a history of doing MDMA," he pointed out. But he does think that, with the right framing and mindset, MDMA could be useful for people who are already at least somewhat open to reconsidering their ideologies, just as it was for him. "It helped me see things in a different way that no amount of therapy or antiracist literature ever would have done," he said. "I really think it was a breakthrough experience."

*Rachel Nuwer is a freelance science journalist and the author of I Feel Love: MDMA and the Quest for Connection in a Fractured World, from which this article is adapted.

--