The weird reasons there still isn't a male contraceptive pill

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany side-effects deemed unacceptable in the male pill have been plaguing women for decades. Is there a double standard?

In 1968, a young man visited his psychiatrist with an awkward observation. He had been taking the drug thioridazine to treat schizophrenia, when he noticed something unusual: his orgasms had become "dry".

Nearly three decades later, the story became the inspiration for a sensational new idea – could a similar drug form the basis of a male contraceptive pill? Eventually researchers discovered another drug with the same ejaculation-suppressing effect, the blood pressure mediation phenoxybenzamine. Neither drug would be safe enough to give to healthy men on its own, but the idea was to find out how they worked – then recreate this mechanism using something else.

Cue many years of research and development – that is, until the therapy hit a major snag.

Though a safe, effective male pill would have the potential to finally unburden women of the responsibility for contraception, and prevent millions of unwanted pregnancies every year, some men found the idea of an invisible orgasm distinctly unappealing. For a proportion of men, the so-called "clean sheets" pill was seen as emasculating. The method eventually lost its funding, and researchers went back to the drawing board (more on this later).

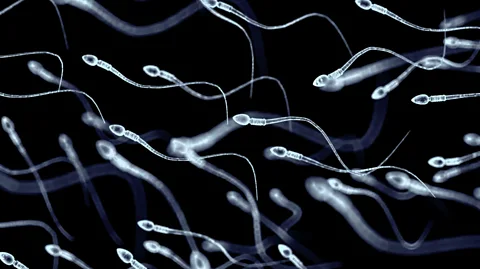

Today the male contraceptive pill is still yet to materialise. This week, research in mice identified a promising new target – a molecular switch that can stun sperm for two hours, rendering its taker temporarily infertile. But though the protein has been hailed as a game-changer, it still has a long way to go before it is approved for use in humans.

In fact, finding effective drugs has never been the problem.

Over the last half century, many possible methods for male birth control have been proposed, including some that have made it to clinical trials in humans. However, each one has eventually met a dead end – even those that are safe and effective have been written off due to undesirable side effects. Several male pills have been rejected on the grounds that they lead to symptoms that are extremely common among women taking female versions.

Why is it so difficult to get approval for male contraceptive pills? And are the challenges more cultural than scientific?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA long history

Male contraception has a long and colourful history.

The ancient Greeks came up with the idea that heating up a man's testicles might reduce their fertility. This turned out to be uncannily prescient – nearly two and a half millennia later, scientists discovered that this is indeed the case.

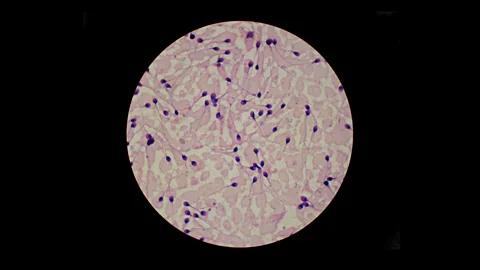

The scrotum naturally acts like an air conditioning system for sperm – by hanging outside the body and utilising a network of veins to exchange heat, they usually stay between one and four degrees cooler than the rest of the body. Some studies have found that even warming the testicles by a few degrees can significantly reduce their viable sperm count, although it's not entirely clear why. Enter one of the first modern methods of male contraception, the hot bath. In 1956, the Swiss physician Marthe Voegeli discovered that men who sat in a bath heated to 46.6C (116F) for 45 minutes every day for three weeks could achieve six months' worth of sterility.

The heat method never caught on, and is not recommended by medical professionals. Currently there are only two safe, effective methods of contraception for men: condoms, which protect against pregnancy 98% of the time if used correctly – though some men say they find them uncomfortable – and a vasectomy, which is more than 99% effective against pregnancy but is considered permanent.

A question of ethics

To get to grips with why side effects are so much less acceptable in male contraceptive pills, it helps to go back to when the female combined pill was first developed – the late 1950s. At the time, there were no widely adopted formal standards for clinical trials, and the drug (a relatively high-dose combination of oestrogen and progesterone) was tested in a series of controversial experiments in several countries such as Puerto Rico. There were just 1,500 women involved, and though half the participants dropped out and three died, the drug was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1960.

Then in June 1964, everything changed. An international confederation of medical associations, the World Medical Association, recognised the need for a new code of medical ethics – particularly after the Nuremberg trials, which saw some doctors charged with enacting medical crimes in Nazi Germany.

The Declaration of Helsinki was a code of medical ethics designed to protect participants in medical research. It included stipulations that scientists would put trial participants first and consider whether the potential benefits to those individuals weigh the risks of causing harm.

"So [after that], there are societal changes in terms of risk and drug research," says Susan Walker, an associate professor of contraception and reproductive health at Anglia Ruskin University in the UK. The combined contraceptive pill slipped through before the rules were made – but it would face a much more stringent testing process if it were developed today.

Modern versions of the combined contraceptive pill are considered to be safe for most women, though they can lead to high blood pressure and blood clots in rare cases. However, they can also cause a number of less serious side effects, including mood swings, nausea, headaches, and breast tenderness. There's even some evidence that it can change your body shape. (Read more about how the pill changes your body shape.)

Which brings us to the next reason male contraceptive pills are held to a higher set of standards – both in terms of acceptable side effects, and safety more generally: to state the medically obvious, men (except transgender men) can't get pregnant.

"I think you have to think about how ethics committees weigh up risks and benefits in terms of a trial, because although you have a couple involved, it's the female partner who bears the physical risks of a possible pregnancy," says Walker. "Weighed against that, inconvenient side effects are [more] acceptable," she says.

In the US, around 700 women die of pregnancy and childbirth-related complications every year, while around 50,000 develop "severe maternal morbidity" – significant short or long-term health effects. Globally, around 295,000 women die during and following childbirth.

Alamy

AlamyNaturally men don't face these risks if they choose to have unprotected sex, so the safety standards for any contraceptives they might take have a higher bar to get across.

Take hormonal male contraceptive pills. Several versions have been developed stretching back to the 1970s, when researchers injected volunteers with testosterone each week for several months and then checked if it had affected sperm production. One early trial found that it was extraordinarily effective – with just five pregnancies after the equivalent of one person using the method for 180 years. Later studies looked at whether this could be increased even further by adding in a second hormone, such as progestin – a synthetic version of the female reproductive hormone progesterone.

However, there was a problem: hormone therapies come with a well-established smorgasbord of side-effects – many of which will be familiar to women taking the contraceptive pill. Testosterone alone can lead to acne, oily skin and weight gain, among others, and this led to some trials being halted early.

"There have been very successful trials of male hormonal contraceptive injections," says Walker, who gives the example of the contraceptive injection, which was found to be almost 100% effective in suppressing sperm concentrations. "That worked extremely well," says Walker. "But it was halted because of worries around side effects, like mood changes and skin changes – which those of us who work with female contraception weren't really surprised about."

A path to acceptance

However, a number of non-hormonal contraceptive options for men have also been proposed, including a vaccine that targets a protein involved in sperm maturation and a kind of temporary vasectomy, reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance (RISUG).

RISUG involves injecting a synthetic polymer into the tube that carries sperm out of the testes – the vas deferens – to block the exit of sperm. It was originally developed as a way to sterilise water pipes, but later adapted to be safe inside the human body. It's currently undergoing Phase III clinical trials – the final stage of testing before a treatment is approved – in India.

However, as with the clean-sheets contraceptive pill, even non-hormonal contraception may be unappealing to some men.

"I think it is true that, in my experience of talking to men about this, men are worried about future fertility and about unknown side effects that may only become known years after using a product," says Walker. "They're worried about the effect on their performance, how they feel about sex."

Funding can also be an issue. In the case of the clean sheets pill, a survey by the Parsemus Foundation – a non-profit based in the US that supports neglected areas of medical research – found that, while 20% of men said they wouldn't take it, an equal proportion said that they would. The rest said they were undecided. And yet, the therapy lost its funding before the necessary animal and human trials could take place.

Walker points out that there are several charities working hard to fund research into male contraceptives, but speculates that pharmaceutical companies may have less incentive to develop them when female contraceptive methods work so well. She suggests they're just not going to get the same return on their investment that they would in a pill-free world.

"I think people are more risk-averse in the world of male contraception," says Walker. "Men are more risk-averse, ethics panels are more risk-averse, and possibly pharmacy companies are more risk averse." Walker has been working in the field of contraception and reproductive health for at least 15 years, and while she used to believe that we'd have a male pill soon, this hope has faded. "I'm no longer optimistic [about this]," she says. "Each method seems to hit the hurdle of acceptability."

Who knows, perhaps the latest promising candidate – the protein that temporarily immobilises sperm in mice – will finally overcome decades of challenges. But it is unlikely many women around the world will be holding their breath.

--