Leprosy: the ancient disease scientists can't solve

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThough it's been around for nearly 3,500 years, scientists are still missing many basic facts about the disease.

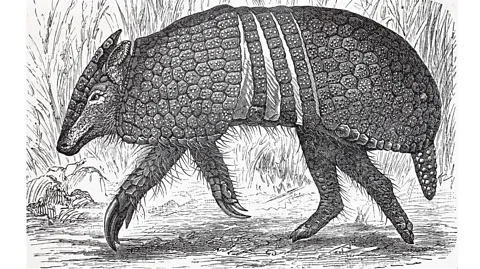

In the wild, one of the only known carriers of Mycobacterium leprae, the bacteria that causes leprosy, is a mammal that looks rather like a large rat with a long snout dressed in leathery armour – the nine-banded armadillo.

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease, attacking the skin, nerves and mucous membranes. This eventually leads to white patches, numbness, muscular weakness and paralysis. But despite its devastating consequences and recorded cases possibly stretching back as early as 1400 BC, to this day much about this ancient malady remains mysterious. No one knows how leprosy originated, nor why some parts of the world are more affected than others. Scientists still don't even know for sure how it spreads – and there still isn't an easy way to check if someone has it.

Take the armadillo. Originally native to South America, this insect-eating animal is now also found across Central America and southern North America. In Brazil, one of three countries that account for most of the 200,000 new leprosy cases every year alongside India and Indonesia, armadillos are hunted for meat. One study by researchers found 62% of the armadillos killed by hunters were infected with M. leprae (similar surveys in the US – where there are between 150-250 new cases in humans reported each year – have found 20% of the animals there carry the bacterium).

In the US, they have been blamed for a rise in cases in Florida. However, like much about leprosy, the degree to which armadillos are responsible for spreading the disease in humans is characteristically unclear. That's not to mention the fact that humans may have given these animals the disease in the first place when Europeans brought it with them to Brazil around 500 years ago.

Why has leprosy remained so mysterious – and proved so hard to solve? Crucially, could this be about to change?

Lost patients

"It's a very complex disease and much about leprosy remains a gripping puzzle, even today," says Gangadhar Sunkara, a drug development scientist and global program head at the pharmaceutical company Novartis. In spite of significant advancements to contain the disease, up to three million people worldwide still live with leprosy and on average, 200,000 new cases are detected every year, according to figures by the World Health Organization (WHO).

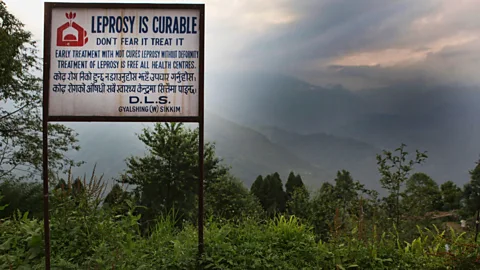

However, in 2020, that number fell to 128,000 cases, says Cairns Smith, emeritus professor of public health at the University of Aberdeen and former director for Leprosy Mission. Roughly 140,000 cases over two years have escaped detection as per WHO data, an oversight that is largely believed to be the result of the strain the Covid-19 pandemic has placed on healthcare systems around the world.

Getty Images

Getty Images"They haven't been diagnosed nor treated and are at severe risk to developing disability," says Smith. Particularly concerning are the numbers of children who have not been diagnosed because of pandemic-related disruptions. At least 15,000 of the cases detected worldwide every year affect children. To catch the disease early would mean preventing life-long disability. "However, these numbers [of children receiving a diagnosis] have dropped to 8,000-9,000 cases," he says. "That means that there are a lot of children who are in danger of developing the disease. Some countries are showing a recovery, but there is still low case detection in countries like Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Philippines. At this time, we're really facing an acute challenge," he says.

The world has made great strides in leprosy treatment in the last four decades, especially with the WHO’s introduction of multi-drug therapy to treat multibacillary leprosy in 1982. Multibacillary leprosy is a more advanced form of the disease, often characterised by skin lesions and disability.

One new treatment is multidrug therapy, (MDT) – a combination of three pills, two of which are taken once a month and another daily. It has had a huge impact in terms of stopping the progression of the disease, bringing us as close to a cure as may be possible and preventing disability among those who are affected. But it hasn't been able to stop new cases from emerging, explains Venkata Pemmaraju, acting team leader of the WHO global Leprosy Programme and who has been working on leprosy related issues for the past four decades.

Old challenges

So what makes this ancient disease so persistent?

According to Sunkara, there are a number of factors involved. For one, M. leprae replicates extremely slowly, so it can take between two and 20 years before an infected person shows any symptoms of the disease. The average incubation time (the time between exposure to the bacteria and symptoms first appearing) for the disease is five years, and in rare cases, a patient may have no symptoms for two decades.

Getty Images

Getty Images"This bacteria has a longer incubation time," says Sunkara. "It takes about 14 days for one bacteria to divide into two in the body, as compared to other disease causing bacteria which can double in minutes," says Sunkara. For comparison, in optimal conditions the common gut bacteria Escherichia coli, some strains of which cause cases of food poisoning, can divide once every 20 minutes.

The long incubation time is problematic not just for the patient, but also those around them. During this time, a patient who doesn't know that they've been infected can pass on the infection to others, particularly to close contacts such as family members.

Once a leprosy infection has become established and developed into the multibacillary form, it can take up to two years to treat, even with a combination of antibiotics. Another issue is antibiotic resistance. The original treatment for leprosy was the antibiotic dapsone, which was discovered to be effective against the bacteria in the 1940s – before then, it was incurable. However, by the 1960s, this drug was becoming less effective.

Today there are several more effective options, particularly the antibiotic rifampicin. The modern approach of using several antibiotics together was partly designed to prevent resistance developing again, but this remains an ongoing concern.

On the other hand, with early diagnosis and treatment, leprosy is an order of magnitude easier to eliminate.

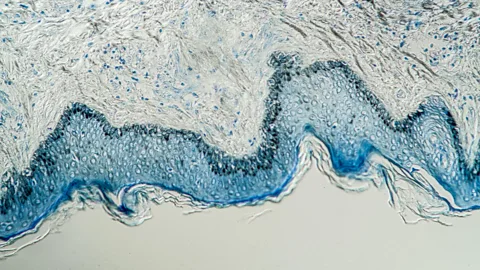

Unfortunately, diagnosing leprosy is extremely difficult. At the moment, the standard method is to take a biopsy. With this technique, a tiny incision is made on a skin lesion, through which blood is squeezed out and tissue fluid and pulp are collected for testing under the microscope. But this method is laborious and expensive, requiring a laboratory and technical expertise. This is particularly challenging in rural areas, where laboratory facilities are not always available, as well as in low-income countries where leprosy is prevalent and resources are scarce. "As a result, many patients are diagnosed late in the course of the disease when nerve and skin damage has already occurred," says Sunkara.

Alamy

AlamyThe issue is compounded by the fact that scientists still don't know exactly how leprosy spreads. It's surprisingly difficult to catch, and often requires many months of close contact with an infected person. The current consensus is that it is likely to be transmitted via droplets in the air when someone coughs or sneezes, but there may be other routes such as through the skin.

Recently scientists also found the bacteria in red squirrels living the UK, but despite extensive efforts, no other animal carriers have yet been found. There have even been suggestions that red squirrels could have been responsible for spreading the disease in Medieval Europe.

Other possible natural reservoirs for the bacteria may exist and it has even been found to survive in soil according to samples analysed from the UK, Bangladesh and India. However, as with armadillos, it's unclear how these wild pools of leprosy might be affecting its transmission in humans.

So, rather than going through the laborious diagnostic process, one option is to blanket-treat people who may have been exposed.

"In order to prevent the spread of leprosy, in 2018, the WHO introduced a significant intervention – close contacts of leprosy patients were tracked down and given a single dose of rifampicin," says Pemmaraju. It was found to have a protective effect of around 55-60%. However, because the pandemic disrupted diagnosis, leading to a missing 140,000 cases worldwide, this would have an impact on leprosy's spread. "Assuming each leprosy patient has 10 contacts, that's over a 1.5 million people who are at risk of developing leprosy because they haven't been able to take a single dose of rifampicin," says Smith.

Rifampicin treatment has had a significant impact in countries like Ghana, says Benedict Quao, who leads the National Leprosy Control Programme in Ghana, which is a member of the Global Partnership for Zero Leprosy. "For the first time ever, countries had medical guidelines that could push political leadership to act," he says.

Though the Covid-19 pandemic is largely responsible for disruption to this new programme, it did introduce one useful new tool: contact tracing. The method has been helpful in tracking down the contacts of leprosy patients in many areas so that they can receive a dose of the preventative antibiotic. The snag is that some countries may not be able to mobilise enough resources for the regular delivery of rifampicin to contacts of leprosy patients, says Quao. "In Ghana we've had that experience in six of our 16 regions and we want to ramp it up. It is a good time for us to have this intervention, but it's not a perfect intervention. Countries recognise that."

Alamy

AlamyIf an effective rapid diagnostic test were available – one that was non-invasive and effective, many of these missing cases of leprosy and close contacts of patients could be diagosed, without the need for blanket prescriptions of rifampicin to potentially healthy individuals. The good news is that these diagnostic tests are currently under development – though they may not be available for some time.

To study the disease and its progression and develop diagnostic tests, scientists often need to inject M. leprae into armadillos, a technique that was first attempted in 1971. "The fact that we cannot culture [grow] this bacteria so easily in laboratory settings is another factor hindering the progress of developing these tests," says Sunkara.

New horizons

Since 2000, Novartis Foundation has partnered with the WHO, supplying drugs free of cost globally for multi-drug therapy. In February 2022, they partnered with Fiocruz for a study that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to accelerate leprosy diagnosis. "I call it applying state-of-the-art technology to an ancient disease," says Sunkara.

There are at least 20-30 other skin diseases that present as white patches on the skin, says Sunkara. Using the AI algorithm to analyse the way light reflects differently off the surface of each skin disease, it's possible to identify leprosy cases, distinguishing them from other similar conditions with far more accuracy. Their study, published in Lancet Regional Health, pegged the accuracy at 90% – but with 1,229 skin images, the data set remains small at the moment. If it succeeds on a larger scale, it might one day be a useful tool to help speed up diagnosis and treatment.

Continuing stigma

While modern advances in the treatment and diagnosis of leprosy have been life-changing for many patients, there's one problem that has never quite gone away: relentless discrimination.

"Leprosy remains a deep-rooted human rights issue," says Alice Cruz, the UN Special Rapporteur on the elimination of discrimination against persons affected by leprosy, a role she's held since November 2017. There are more than a hundred laws that discriminate against people with leprosy worldwide, creating a strong stigma that can act as a barrier for getting treatment, she says.

In some countries, leprosy is grounds for divorce. In India, this was the case until laws were amended in 2019. Many people affected by the disease still struggle to get jobs, and the disease can hinder their access to healthcare and education.

"Countries should do everything in their power to have discriminatory laws abolished and to put in place policy that can guarantee economic and social rights to people affected by leprosy," says Cruz. "Going forward, we should ask ourselves the question: are our healthcare systems working to afford full accessibility to persons affected by leprosy? This is because leprosy is much more than a disease, it became a label that dehumanises people who are affected by it."

* This article was updated on 25 January 2023 to correct an error that stated nine-banded armadillos were endemic to Southern and Central United states and native to India and Indonesia. A clarification that red squirrels in the UK have also been found to carry the bacterium responsible for leprosy was also added.

--