Autism: Understanding my childhood habits

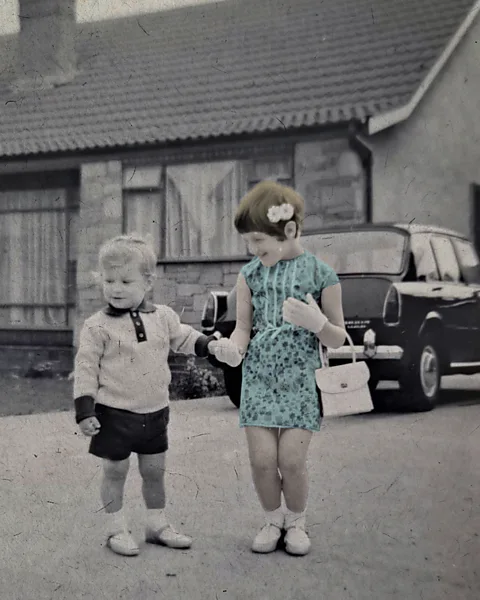

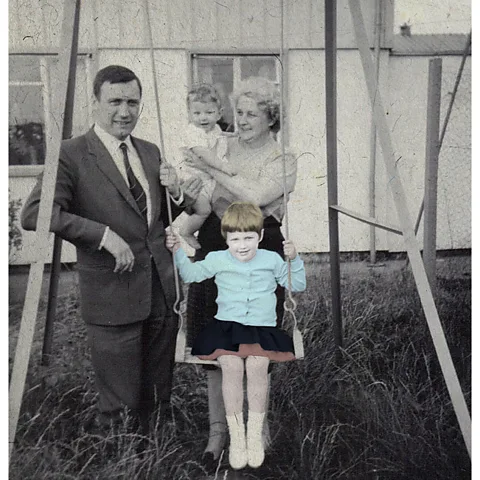

Sue Nelson

Sue NelsonJournalist Sue Nelson was diagnosed with autism late in life – and it made her see some of her childhood habits and preferences in a completely new light.

No one knew I was autistic as a child but, looking back, there were a number of sensory clues. Apart from a tendency to repetitively stroke soft fabrics or run grains of sand through my fingers, I also found swirling and gentle rocking mesmerisingly soothing.

When I was eventually diagnosed with autism much later in life – at the age of 60 – it gave me a new understanding of how and why I behave the way I do. That includes certain childhood behaviours, from fabric-stroking to the way I played with toys and insisted on specific foods. But it also raised questions, such as what might these preferences reveal about how children with autism experience the world? And how could we use this understanding to help children fulfil their potential, form friendships, and enjoy life?

As a science journalist, I naturally look to scientific research for answers – and there is a growing body of evidence providing fascinating new insights into behaviours that were long considered a mystery.

Autism Spectrum Disorder, or autism, affects one in every 100 children, according to the World Health Organization. A developmental condition caused by differences in the brain, it can affect how a person absorbs, processes and responds to information. It is usually categorised along a spectrum, from mild to severe. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, this spectrum is divided into levels 1, 2 and 3, where those with level 3 autism require "very substantial support". Within those categories, there is a huge diversity of needs and experiences, as well as some common traits.

Take the swirling and rocking, for example. These kinds of rhythmic repetitive actions – a common feature of autism – are known as self-stimulatory behaviour, or "stimming". They can also include movements like hand flapping, foot shaking and finger flicking. Even today, I can't resist fondling cashmere or faux fur clothes in shops and will often furtively touch the back of someone's irresistibly soft coat in public. I also body rock occasionally, though only ever in private, because I know it makes most observers uncomfortable.

Stimming can appear pointless or even disturbing to others. As a result, there are various treatments aimed at changing or reducing it. But as with many behaviours associated with autism, the person engaging in it is not necessarily experiencing what you might think.

Sue Nelson

Sue NelsonWhile some forms of stimming can be harmful and should be addressed, such as a child hitting their head repeatedly against a wall, others are useful and helpful. They are not out-of-control movements, but instead serve a purpose and can be a calming coping mechanism. For me and many others, young and old, rocking reduces anxiety.

"It's something that's repetitive and soothing but even in the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM 5 by the American Psychiatric Association], the 'psychiatric Bible', these sorts of behaviours are classified as purposeless," says Steven Kapp, a developmental psychologist at the University of Portsmouth who was diagnosed with autism aged 13. "So, I think a lot of researchers have struggled to understand why people engage in these behaviours."

Kapp's autism helps inform his work and, in recent years, there has been an increasing attempt by other researchers to draw on autistic people's views of their own experience. This can be very different from the impressions or judgments of those around them.

For example, outside observers may interpret certain repetitive movements, including hand flapping, as a distress signal. But 80% of respondents to a 2015 survey of people with autism reported that they enjoyed stimming.

Kapp led a study of autistic adults to explore this behaviour further. Many said they used stimming in response to sensory overload, including in "confusing, unpredictable, overwhelming environments" that caused them anxiety – which was then calmed by the movement. But stimming was also used simply as a release of any high emotion, including happiness or excitement.

However, the study participants tended to suppress these soothing and enjoyable movements in public. Several had "stimmed happily as young children" but hid or changed the behaviour later, in adolescence, when they became aware that others judged them negatively for it, according to the study.

"There are plenty of autistic people who still engage in stimming," says Kapp. "But we're less likely to do it in public because [others] often don't understand, so they stigmatise it. When people do understand, they're more likely to accept it. That's what the study I led found." The participants reported that when among accepting friends and family, they stimmed openly.

Sue Nelson

Sue NelsonTomato soup and chocolate pudding

So-called repetitive restrictive behaviours (RRBs), which can include stimming as well as certain routines and rituals, can also affect family dynamics. While my tendency as a child to constantly rearrange toys into categories such as size or colour rather than play with them – common among autistic children – didn't affect the family much, I suspect the only-eating-tomato-soup-and-chocolate-pudding phase was a bit more of an issue. Fortunately, my parents accepted this and didn't turn the dinner table into a battle ground.

In fact, many autistic children are labelled "fussy eaters". One large study found seven out of 10 had atypical eating behaviours, the most common being limited food preferences. Research also shows that children with autism are extremely sensitive to flavours, smell and textures. It's that sensory perception aspect again and, for me, it's relatable. After that initial restrictive food period during childhood, I am now addicted to a variety of highly spiced foods containing chilli and garlic. However, I still find it difficult to eat a chopped egg sandwich without adding crisps for textured crunch, and just the thought of white fish in a white sauce on mashed potato makes me queasy.

Of course, many people have food preferences and aversions, not only those with autism. But the way such sensory experiences, emotional aspects and emotional regulation interact in people with autism, is still not fully understood. This includes the emotional impact of sensory overload, which can be very powerful.

Uta Frith, emeritus professor of cognitive development at University College London, has spent her career studying the behaviour of children with autism. In the past, "there was a theory that emotions were absent or disturbed in autism, which I think is just not true", Frith says. "On the contrary, emotions are very much in evidence, including high anxiety as well as anger and aggression." This can lead to tantrum-like meltdowns, often caused by sensory overload.

Kapp says that when someone is overstimulated by light or sound, "maybe removing oneself from the environment or getting out an accommodation like wearing headphones or sunglasses, or something to dull some of the sensation" could help. "Because a lot of autistic people are hypersensitive and will perceive it more painfully or sharply than others," he says.

Friendship and connection

Research – and especially, listening to the voices of people with autism – has also helped overturn a number of misconceptions, such as the common assumption that people with autism are not interested in social interactions. As one study notes, the assumption that autistic people are solitary by nature is "flatly contradicted by the testimony of many autistic people themselves" – myself included. The desire for solitude is usually, for me, only after socialising. It's a mental recharging of batteries to balance stimulation overload.

Certain behaviours, such as low levels of eye contact, may be seen as indicating a lack of social interest, but may actually be a sensory coping strategy, the study suggests. Even researchers can fall into the trap of overly relying on eye contact as a measure of babies' and children's social engagement, some argue.

When children with autism are asked about their experiences, they tend to report difficulties in understanding and forming relationships with other children, but also tend to say that they try to initiate such friendships and feel lonely if there is a lack of interaction. "This suggests that children with these traits may benefit from careful monitoring and interventions focused at improving peer relationships," according to the authors of one study. In short, children with autism do enjoy and benefit from friendships, but may need some help forming them.

This can be easier when there is a way to meet the children on their own terms, research suggests – for example, by supporting another typical trait: special interests.

Sue Nelson

Sue NelsonWildflowers, buttons, badges and space

Scientists are only beginning to understand how and why people with autism commonly form intense interests, and the benefits this can bring. One study found that they develop an average of nine special interests, starting around the age of five. These interests can include certain objects, music, computers, nature and gardening.

As a child, mine were mathematics, wildflowers, science, buttons, badges, space and superheroes. Not much has changed and, for others like me, pursuing their own interests generally has a positive effect on wellbeing and social contact. When children and young people with autism engage with their passions this was found to have a wide range of benefits, such as boosting emotional and communication skills.

There will always be activities that autistic children tend to instinctively dislike, even something as routine as haircuts. I never enjoyed having my hair washed as a child and visiting a hairdresser remains an uncomfortable experience. While I always ensure there will be no surprise head massage during a shampoo, I am anxious in case they forget. For some, fear or distaste is induced by the sound of scissors or the feel of cut wet hair on the skin. It's important to understand that these simple sensations, which many people enjoy, can cause others distress.

What is often harder for parents is when their child doesn't want to engage in affectionate physical contact or hugging, due to differences in sensory processing and social communication. Parents trying to play some kind of simple give-and-take game may find children with autism are not interested, and parents may find this hard. "It's that turn taking, that reciprocation, a sort of copying [that children with autism may struggle with]," says Frith. "The easy understanding of what another person does."

Individual enjoyment of social and physical contact can vary hugely. Research into the effect of the Covid-19 lockdowns on children with autism, for instance, found that some children thrived while the behaviour of others worsened. The wider social environment can also play a crucial part.

Jess* lives in Hartlepool in the north of England. Her eldest son was diagnosed with autism aged six, in 2015. Since then he's been expelled from several schools after sensory overload led to meltdowns and aggressive behaviour.

"When the school system is completely flawed for tackling autism, a few fidget toys isn't going to work," says Jess. "What worked was when he moved to a school with more space and a sensory room where kids could let rip."

As a result of the increased space and understanding, her son's behaviour improved. "The atmosphere was completely different and that made a difference. There were teachers who believed in him and could communicate with him. He could work outside the classroom if he wanted as they were much more flexible," Jess says. "He still got excluded occasionally but we weren't seeing the same behavioural issues."

Jess' son initially struggled with lockdowns. Eventually, Jess stopped trying to persuade him to do his homework: "He often went on long bike rides and was, therefore, much happier."

Jane*, who lives with her husband in Aberdeen, Scotland, insisted throughout the pandemic that their teenage son, who has autism, continued to attend school. He "has transition issues so not leaving the house would have been his perfect scenario," she says. "Each day I do lots of coaxing and reassurance and tell him things will be ok. It doesn't work as well as it used to, but school is non-negotiable."

Frith has observed that social attitudes about autism have shifted over the past few years, but not always in helpful ways.

"People have been through a cultural change in understanding neurodiversity and autism has become a favourite of fiction and films," says Frith. "But it's focussed on very few features, in particular positive features." The kind of autism most often being presented in popular media would be categorised as mild, she says. Also, on-screen characters with autism are often portrayed as being intellectually gifted. The danger, she says, is that this misses out those who need more support.

"One thing we cannot completely overlook, but tends to be with some forms of autism, is that there can be an intellectual impairment," says Frith. Acknowledging this can be an important part of accepting the child for who they are.

For every family, learning about autism ultimately means learning about their child's unique experience of autism.

"There is greater understanding of neurodiversity, complex profiles and differences people may have rather than seeing autistic children as objects of pity or fear," says Kapp. "But there is still a lot of work to be done."

* The names of the parents quoted in this article have been changed to protect their children's identity.

--