The 120-year search for the purpose of T. rex's arms

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf the world's most notorious carnivore had survived the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, it might have eventually lost its arms altogether.

The end of the season was approaching rapidly – the last shot at success in what had been a very expensive expedition.

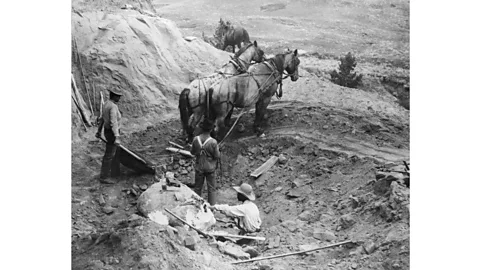

It was August 1902 and Barnum Brown had taken a team of palaeontologists deep into the strange, undulating landscape of banded hills in the Badlands of Montana. Amid soaring temperatures and caking dust, they searched for fossils – hacking away at the golden-brown earth with chisels and pickaxes, carving out mini quarries at scattered locations, sometimes uncovering half-decent finds only to abandon them. They urgently needed something good to send back to the American Museum of Natural History.

From his office in New York, Brown's boss was just as anxious as his distant employees. Henry Fairfield Osborn had recently taken delivery of their latest prize, a vast hunk of rock containing the skull of a kind of early duck-billed dinosaur. It had been tenderly carted all 2,100 miles (3,379km) from the dig site – a labourious, risky journey involving horses, railway lines and lots of heavy lifting. Only then did Osborn discover that hidden within its stony tomb, the fossil had been a crumpled, misshapen mess all along. The specimen was banished to the museum basement, but he felt that it might as well have been thrown away.

But now things were looking up. Brown had uncovered a number of bones from a promising large carnivorous dinosaur that was entirely new to science. Its hip bone was 5ft (1.5m) long, let alone the rest. This was Tyrannosaurus rex – the first ever discovered. Brown had never seen anything like it.

In a letter to Osborn, Brown wrote: "There is no question but what this is the find of the season so far for scientific importance [sic]." Little did he know, it was more like the find of a century – a discovery that would transform our understanding of dinosaurs and galvanise public interest in this previously obscure group of ancient creatures well into the modern era.

But right from the beginning, one aspect of these kings of the "tyrant lizards" was deeply mysterious: their puny arms. Brown's T. rex skeleton was missing all its fingers and both its forearms, which were drawn on early portraits using surprisingly accurate guesswork – prompting speculation that they surely couldn't really be that stumpy. What could have been their purpose? And how did they end up being so small?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBizarrely, they were. Today T. rex is almost as famous for its withered little arms as for its enormous teeth – they're so totally out of proportion, they almost look like they've been plucked from another species and simply stuck on, in a throwback to the hilarious blunders of bone assembly from the 19th Century (such as the time Stegosaurus' signature diamond-shaped back plates were added to its tail instead).

"You can look at his arms and say, well, these are ridiculous. They're so different than anything around today, what is the point," says L J Krumenacker, a palaeontologist at Idaho State University.

With arms that might measure just 3ft (0.9m) long on a 45-ft (13.7m) individual, this formidable carnivore's hilariously small appendages have been a source of intense speculation ever since they were discovered – despite decades of studying them, to this day no one has any idea what they're for.

A missing set of bones

Though Brown's original T. rex was unearthed in 1902, it would be some time before scientists first gazed on its strange arms. The initial skeleton included little more than a sparse assortment of jumbled bones – among them were the pelvis, a single shoulder blade, a single upper arm bone, and part of its skull. Six years later, the fossil hunter uncovered another individual some way to the south, at Big Dry Creek in Colorado. This was an unusually perfect specimen, and its towering figure inhabits the American Museum of Natural History to this day. But this one also didn't have its arms.

For most of the following century, scientists could only make educated guesses about what T rex's forearms might have looked like. Many were based on its cousin Gorgosaurus, another tyrannosaur which also roamed North America during the Late Cretaceous, around 66 to 101 million years ago. Then on 5 September 1988, the rancher Kathy Wankel inadvertently stumbled across a strange protrusion emerging from the earth near Fort Peck Lake in Montana – it was like the corner of an envelope, she later told the Washington Post.

Alamy

AlamyWankel didn't have time to extract her find that day, but she didn't forget about it – she returned a month later and dug out a set of long bones, which she drove to the Museum of the Rockies, hundreds of miles to the west. The director of palaeontology agreed to take a quick look. They soon realised these were no ordinary dinosaur fossils, they were T. rex arm bones, complete with the mystery lower half that had been missing for so long.

Eventually the rest of the dinosaur was excavated to reveal a 7,000lb (3,175kg) monster that was so perfectly preserved, it was still in its original death-pose, neck back, like a dead bird. This was the "Wankel Rex", and its forelimbs were even smaller than anyone had imagined.

A stubby little puzzle

Over the past century, scientists have uncovered tantalising details of many aspects of T. rex lives – from their slow, lumbering walking gait as they stalked through the swampy forests of western North America, to their unfortunate susceptibility to an illness more usually associated with human kings, gout. The palaeontologist Elizabeth Boatman and colleagues may have even glimpsed their original collagen preserved in some exceptional fossils.

So far, the purpose of the dinosaurs' stubby limbs has proved elusive – but not for the want of trying.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOne early idea came from Osborn, who gave T. rex its name. "He saw these very small, curiously tiny arms and made a comparison with small fins that that are present on modern-day sharks, says Scott Persons, head curator of the Mace Brown Museum of Natural History, South Carolina.

Male sharks use these two fins at the base of the tail – claspers – to grab onto the female during mating, which can be a slippery business underwater (they're also used to perform the act itself). "So he envisioned a pair of tyrannosaurs entwined in primordial courtship with the male on top and using those arms to grip a hold on the female," says Persons.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPersons explains that it was perfectly possible Osborn could have been right. If male T. rexes – which are notoriously difficult to identify – had turned out to have arms that looked different to female ones, it would make sense that they were using them for sex. "Now, that's not the way things have gone down," he says. Instead, as more and more individuals have been uncovered – there are now at least 40 – scientists have confirmed that they all have the characteristically small arms and they always look pretty much the same.

Another, potentially comical, possibility is that T. rexes may have used their little arms to get up off the ground. With up to 15,500lb (7,031kg) bodies – equivalent to the weight of a large African elephant – they may not have found it easy to manoeuvre out of a resting position, or get back on their feet in the event that they fell over. (Many living animals struggle with this to this day, such as tortoises, which often rock themselves upright when they end up on their backs.)

"So when they were rising from a crouched position, they could use the arms to do a tiny tyrannosaur push-up," says Persons. However, there is a small flaw with this theory – the carnivore's arms wouldn't actually have helped that much. "You've got to understand that that really only helps the tyrannosaur with the first two feet. And then it's got like another 15 feet to go off the ground," he says.

Another controversial idea, put forward by a single scientist in 2017, is that adults like the Wankel Rex may have used their stubby arms as weapons – perhaps holding their victim in their jaws or pinning it down with their bodyweight, before ripping and slashing at it. Underpinning the idea is that though they're tiny, T. rex's arms are surprisingly muscular. He calculated that even with its 3ft (0.9m) limbs, these eviscerating actions could have done some serious damage, creating gashes several centimetres deep and at least a metre long in a matter of mere seconds.

"Now I personally think the arms are just too ridiculously short for that to make sense," says Persons.

However, there is also the possibility that they had no function whatsoever – T. rex's tiny arms were the last vestiges of once-useful appendages that had long ceased to be necessary. If they were simply hangovers from another time, like the human tailbone, the world's most terrifying predator may have had an even more bone-chilling future: eventually evolving to lose its arms altogether, to resemble a kind of horrifying land-shark.

Alamy

Alamy"If… the reign of tyrannosaurus had not been cut off by the asteroid impact, if we sort of, roll the tape forward in time, to a theoretical five or even 20 million years down the road, do I think that the arms of tyrannosaurs would have continued to shrink? Yes," says Persons. "Do I think they would have eventually become completely lost? I definitely think that's a possibility."

Persons explains that even if T. rex didn't have a major function for its arms, serving any small purpose whatsoever could have been enough to preserve them – though they may have eventually become tinier still. This could include females using their arms to dig a nest, as sea turtles do. It might just also include grooming, he suggests – packs of 45ft (13.7m) monsters sitting around and gently clawing at each other's feathers (as many paleaontologists believe they were covered in them).

Scientists have now found entire groups of fossilised tyrannosaurs at three separate sites across North America, which some have interpreted as evidence that they were more social than you might think. One team has even proposed a collective noun for these congregations: a "terror" of tyrannosaurs. As a result, some experts have speculated that social T. rexes might have found their tiny arms useful during feeding frenzies. If the carnivorous dinosaurs ate in packs like scavenging hyenas, crowding round the carcasses of Triceratops and other enormous contemporaries, it might have been tricky to keep larger arms out of the way of a rogue pair of jaws.

"This kind of quirky idea was that their arms were small enough that they didn't get in the way of all these guys fighting over food with giant mouths, so they weren't basically biting their own arms," says Krumenacker.

However, Krumenacker points out that it's notoriously tricky to test such ideas, partly because there are no analogues alive today that would make for an easy comparison. "With a great big head and little tiny arms, the closest we can get is maybe some ground-dwelling predatory birds," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn alternative is to use basic physics.

Intriguingly, one of the latest ideas is that the dinosaur king's arms may have withered to their shrunken form to serve an important purpose – there was a reason they needed to be so puny. It's possible their small size helped them to have the most enormous head and powerful bite possible: the bloodcurdling silhouette of the average T. rex was no accident. To understand why, it helps to look at their body plans.

Earlier this year, researchers revealed that another dinosaur – Meraxes gigas, a 9,000lb (4,082kg) giant which inhabited Patagonia during the Late Cretaceous period – had an uncannily similar body plan. Though both dinosaurs were only distantly related, they both had enormous bodies with oversized heads and vastly undersized arms. The idea is that as the predators' heads and bodies got bigger, their arms got correspondingly smaller, perhaps to help them balance. To get why these proportions were necessary, it helps to look at their teeth.

As it turns out, T. rex's thick, conical teeth were not like the piercing needles or razor-sharp swords of some animals' jaws. Instead, they're more like serrated bananas: sharp on the edges but not at the ends. "You cannot cut yourself on the point of a tyrannosaur tooth," says Persons, though he points out you can do it on the edge. That's because rather than mere flesh-slicers, they were designed to be bone-crushingly powerful, able to crunch down on their enormous prey and rip off chunks that could be swallowed whole.

But this strategy requires some serious brawn – the heavy teeth need sturdy jaws to withstand the bite impact, which in turn need a whole load of muscle to allow them to work properly. In short, their heads and necks had to be vast. "And that's potentially a problem. Because all carnivorous dinosaurs, from allosaurus to velociraptor, are built a little bit like a seesaw – they stand on two legs," says Persons. With T. rex's supersized head, larger arms would tip the front end forwards, or necessitate a larger tail as a counterbalance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlas, it's also possible that we may never know the true function of T. rex's arms. Like discovering the long-tubed passion flowers of North and South America without finding the hummingbirds that dip their long beaks into them, sometimes the context you'd need to understand a feature has been lost to the fossil record. After more than 66 million years – in which time volcanoes have sprung up and gone extinct, islands have been formed and lost, and tens of thousands of species have come and gone – the nuances needed to understand certain behaviours may be too far gone to unravel.

All this interest in the odd arms of an animal that went extinct 66 million years ago may seem odd. But apart from curiosity about something so intrinsically interesting, Persons thinks he knows why. "We human beings are probably a little bit too preoccupied with the importance of our arms and our hands, because they're so gosh-darn critical to our survival," he says.

As the primary way we interact with our environment, it's hard to imagine giving them up on purpose. "And here we've got this incredibly successful, very scary-looking, animal, and it seems to want very little to do with them," says Persons.

*Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett

--