Eucatastrophe: Tolkien's word for the "anti-doomsday"

Amazon

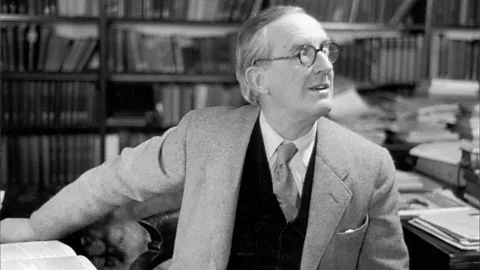

AmazonBefore he wrote The Lord of the Rings, the author JRR Tolkien coined a word – "eucatastrophe" – that scholars would still be writing about 70 years later. What did he mean, and why could it relate to the very real story of humanity?

In the early 1940s, JRR Tolkien wrote an essay about fairy stories – and why they matter. Based on a lecture he had delivered in Scotland, it not only defined and shaped his views as a fantasy writer, but would prove influential for years to come.

Fairy stories, Tolkien argued, are not only meant for children. Immersing oneself in fantastical worlds with wizards, talking trees and dragons is a "natural human activity". Such tales have a purpose that nourishes the heart and mind, he continued. They can help us to remember and recover what may have been lost or taken for granted; they offer escape from one world to another, and ultimately, they bring consolation, and the reassurance that there can be happy endings.

At the time, Tolkien had only recently published The Hobbit, and was just beginning to work on The Lord of the Rings. It was a pivotal moment. As a writer, he was shifting into a more serious, authentic voice and tone. The literary scholar Verlyn Flieger describes the essay as "Tolkien's definitive statement about his art" – but also much more.

In particular, Tolkien wrote about what makes a happy ending so powerful in stories. And to do so, he came up with an intriguing coinage: fairy stories, he suggested, often feature a "eucatastrophe" – this was, he suggested, a "good" catastrophe. So, what exactly did he mean? And could such events happen in real life too?

In the present day, Tolkien's idea of the "good catastrophe" has attracted the attention of scholars who study existential risk and humanity's future prospects. It turns out that eucatastrophes may matter beyond fairy stories – and identifying the conditions that lead to them could be necessary if we want to thrive as a species.

You may also like:

According to Tolkien, a eucatastrophe in a story often happens at the darkest moment. When all seems lost – when the enemy seems to have won – a sudden "joyous turn" for the better can emerge. It delivers a deep emotional reaction in readers: "a catch of the breath, a beat and lifting of the heart", he wrote.

In The Hobbit, it'd be the sudden arrival of the eagles in the Battle of the Five Armies, while in The Lord of the Rings, it's the moment Gollum unexpectedly falls into the cracks of Mount Doom, destroying the One Ring. But many other stories feature such turning points, whether it is the kiss that revives Snow White, or the destruction of the Death Star in Star Wars.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe ancient roots of Lord of the Rings

It's sometimes assumed that Tolkien was inspired by the most famous ring in opera, Wagner's Ring of the Nibelungs. Both Tolkien and Wagner drew inspiration from the same sources, chiefly Nordic sagas. For Tolkien, the obsession began in childhood, when he fell in love with the story of Sigurd the dragon-slayer.

But we also know that Tolkien was familiar with the site of a Romano-Celtic temple to Nodens, a Celtic healing god. Tolkien worked on the excavation of the site, named Dwarf's Hill, and became fascinated by its folklore. In particular, he investigated Latin inscriptions, one of which brought down a curse on the thief of a ring.

Read more about the ancient roots of JRR Tolkien's stories on BBC Culture and also learn about how he influenced 1960s hippy culture.

As Tolkien wrote: "The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairytale, and its highest function. The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending: or more correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous 'turn'… is one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well… it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur."

Literary scholars have deployed Tolkien's framing to describe such turns within narratives ever since. But in recent years, the word has drawn attention in other academic fields too – specifically among those who think about the deep future of humanity.

A few years ago, the philosophers Owen Cotton-Barratt and Toby Ord at the University of Oxford were writing a paper about how best to define existential catastrophes – those events that could threaten our species' long-term potential: supervolcanoes, nuclear winter, pandemics, or the advent of a global totalitarian regime.

The pair realised, though, that their field lacked a word for brighter abrupt changes: moments when humanity's prospects suddenly improve. So, they reached for Tolkien.

"Tolkien talks about the eucatastrophe as the sudden and surprising turn for the better. This is the concept that we were trying to name," Cotton-Barratt explains. These would be "moments when things, in expectation at least, suddenly get a lot better", he says. "And the world looks like it's in a much better position."

Eucatastrophes have already happened on Earth. The origin of life might be one example. "When life first arose, the expected value of the planet's future may have become much bigger," write Cotton-Barratt and Ord. Against all odds, after billions of years of barren sterility, fire and fury, living creatures finally emerged.

Others have suggested that eucatastrophes for one group can follow catastrophes for another. For example, an asteroid may have killed off the dinosaurs, but it also enabled mammals – and eventually, us – to diversify and thrive.

Ben Rothstein/Prime Video

Ben Rothstein/Prime VideoWise Words

Welcome to Wise Words, a BBC Future series that explores the vocabulary required to describe a rapidly evolving world. We’ll uncover lesser-known words and phrases that label previously hidden phenomena, guided by the belief that novel language can unlock novel understanding.

Examples within human history are a little harder to come by, but Cotton-Barratt (tentatively) suggests that the intellectual flourishing of the Enlightenment might be another case of a sudden, positive trajectory change. Some might say that the ends of World War One or Two could also count. For Tolkien himself, a Christian, the ultimate human example was the life of Jesus: his birth, and eventual resurrection: "There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true," he wrote.

Existential hope

But why bother labelling such events at all? For those who want the future to go well, the reason it matters to talk about possible eucatastrophes is that we could, in principle, prepare the ground for them to happen. "It doesn't have to be totally unanticipated," explains Cotton-Barratt. "We don't need to be blindsided."

So, for instance, a possible eucatastrophe might be a specific discovery enabled by investment in science, such as the emergence of a miraculous form of clean energy, like nuclear fusion, just as the world teeters on the precipice of total climate catastrophe. Or it could be a moral revolution: where humanity navigates through dark moments to come to a whole new realisation about how to live peacefully and harmoniously on this planet.

Amid a time of crisis and conflict, preparing for such turns for the better might be difficult to imagine. But Cotton-Barratt, Ord and others suggest that we owe it to future generations to ensure that we don't neglect or ignore opportunities that could help them to encounter these moments of potential flourishing. There's no doubt that we urgently need to reduce existential risk, they say, but we ought to also seek ways to increase what they call existential hope.

"The world is radically different now than it was in centuries past – particularly if you go back many centuries," says Cotton-Barratt. "I do think it's very possible that the world could be radically different again." Building a world where "we are robustly well-prepared to face whatever obstacles come" is therefore not just prudent – it is also necessary if we want our great-grandchildren to live in a better world than we can currently imagine, he argues.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo, could Tolkien's eucatastrophe word soon enter the vernacular? Cotton-Barratt isn't so sure. "It's not a term I ever can really imagine going mainstream," he acknowledges. "It just sounds confusing to people. I think it's easy for people to hear it and think it's a type of catastrophe."

For that reason, the Foresight Institute – a non-profit futures research institute based in San Francisco – recently offered a prize for a better word. They also asked listeners of their podcast for suggestions.

The ideas included:

- Benepeteia – based on the Greek word peripeteia, another suggestion, which means a sudden reversal of fortune.

- Euflection Point – also drawing on the eu- prefix, meaning "good" or "well".

- Anastrophe – if "catastrophe" is a turn down (kata-), its opposite (ana-) would be an upturn.

- Delajoy – a feeling of transcending joy.

- Plethoration – the realisation of abundance.

- Gleðitár – an Icelandic word for "tears of joy"

- Existential Windfall

- Lighter suggestions like Fantastrophe, a Hyper-gooding, or simply: Big Happy Surprise.

- The winning entry? Efflorescence – a process of unfolding and blossoming.

Would Tolkien have approved? Perhaps: he once said that language invention was his "secret vice". And his interest in philology – the study of linguistic evolution – means he might expect his influential term to eventually fade away.

For the time being though, the term eucatastrophe has stuck – and maybe one day, you and your descendants might actually be fortunate enough to see one happen.

*Richard Fisher is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @rifish

--