The Epicurean guide to digital life

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyIt's an Ancient Greek philosophy known for its lessons on material existence and pleasure-seeking. So what might Epicureanism say about living well on social media and the internet? Nathan Dufour Oglesby explains.

In all likelihood you're reading this on a screen.

Tens of millions of bits of digital information display this text within your perceptual field, while hundreds of billions of neurons interpret the visual information received from your optic nerve. A sprawling interplay of physical processes, theoretically reducible to infinitesimal signals and bits, underlies your experience of reading an online article.

I try to keep this physicality in mind, as more and more of my life occurs on screens. My main occupation is making comedic music videos about philosophy, ecology and other topics, for my YouTube and TikTok channels – it’s a joyous job, but one that comes with an overwhelming abundance of screentime. Hence, even when I'm using my digital devices to pursue my desired ends, writing and creating, an anxiety sometimes sets in – "Is this okay? Am I letting my very life vanish into the pixelated vistas of my video editing software, my docs? Is this a life at all?"

As these forms of experience come to predominate, and as we approach the frontier of an augmented reality, in which computer-generated content is woven into the fabric of perception, I often try to remind myself that even though there’s something seemingly "immaterial" about digital and virtual experience, it’s all still ultimately physical.

This thought helps me to interpret, and to manage, that experience.

I reason that I can live a good life, even if a lot of it is spent on my computer – so long as I regulate my inputs and outputs conscientiously, the same way I would for any other physical process, like eating or exercise. You are what you eat, and, in a different but fundamentally related sense, you are what you scroll through, watch, comment on and download. It's all matter, and matter matters.

Now there's a lot packed into this claim, that "everything is matter", or reducible to it. It involves perennial philosophical quandaries, about which my own convictions are ultimately fluid, agnostic and eclectic.

But when I'm thinking about my digital experience, seeking to make sense of the various layers of virtuality that overlie my day, I find myself turning to a particular school of Ancient Greek philosophy called Epicureanism. What, then, can this 2,000-year-old philosophy tell us about how we live in the digital world today?

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyTo begin with, the Epicureans were materialists. They believed that all of existence results from the chance collision of indivisible material bits called "atoms", cascading in the infinite void. We now understand atoms, via modern physics, as things that can be further divided, but by this term the Epicureans simply meant the smallest bits that could be conceived. The word literally means "indivisible" (atomos). These bits aggregate into larger bodies, and in the process of cosmic evolution have brought about life forms such as ourselves.

I use the word "bits" deliberately, to evoke an analogy with the digital. Not only is a "bit" a small quantity of something (such as an atom), it is also the term for the smallest unit of data in a computing system. These bits are physical things – in early computing they were housed in sequences on punched cards, now they are embodied as voltages on tiny transistors. Different sequences of bits (ones and zeroes), different digital information. Different shapes and arrangements of atoms, different bodies.

The Epicureans believed that even the contents of our minds – our thoughts and perceptions – are comprised of very fine atoms of a certain kind. On this basis they asserted that all perceptions are equally real – even dreams and optical illusions are real, in the sense that they are made of actual, material stuff just like anything else.

This doesn't mean that all perceptions are equally trustworthy – one must interpret which pieces of perceptual information are the most reliable. But this theory is pertinent to modern digital experience because it reminds us that the contents of our screens, like the contents of our minds, are not less real than the external sense objects we perceive, just different.

As the philosopher David Chalmers puts it, in two helpful phrases: "information is physical", and "virtual reality is genuine reality". (Chalmer's recent book Reality+ goes into many of these issues – such as how to define "virtual" and "physical" at greater depth. Also, for a lengthier treatment of the Epicurean theory of perception, see this article by Emma Woolerton.)

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyStill, how does this help? Just because I'm living a "real life" when I spend an entire day shrouded in the luminescence of my laptop screen, doesn't mean I'm living the "good life". What would an Epicurean have to say about the qualitative aspects, and the ethical value, of digital experience in the 21st Century?

Epicureanism emerged in the Hellenistic period (323-31BC) – an era which, not unlike our Information Age, was characterised by a radical shift in the technology of media. Book culture was becoming more widespread, texts were being collated, canonised and produced at an increasing rate, and Greek language and culture was spreading throughout the Mediterranean region. It was an era of social and political upheavals, and new ideas arising to confront new realities.

You may also like:

Amidst all these changes, Hellenistic philosophy tended to put great emphasis on ethics, and the application of its theories to the pursuit of the best possible life. It wasn't just an academic discussion, it was about creating and pursuing a spiritual discipline founded on a rigorous conception of the nature of things (See Martha Nussbaum's Therapy of Desire for an extensive treatment.)

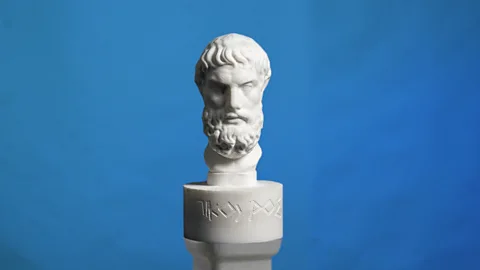

The Athenian Epicurus was paradigmatic of this trend. He began his system of thought from the atomic theory of matter described above, drawing on philosophers from the preceding century. But his most well-known contribution to philosophy is the ethical theory that he derived from it – a radical endorsement of the pursuit of pleasure.

Epicurus believed everything reduces to atoms and void – including our mind (psyche) – and so rejected the conception of the immortal soul, which had been central to prior religious and philosophical thought. The gods, he held, may exist – but even if they do, they have nothing to do with us, and hence give us no moral obligations, no divine law, and no higher purpose. Therefore, the best thing you can do, and in fact the highest good, is to pursue a life of pleasure.

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyDespite how that sounds, the Epicureans did not feel that this consisted in a life of sex, drugs and dithyrambic poetry (Dionysiac party songs). Rather, they felt, the pursuit of pleasure would be best effectuated by a simple life – and Epicurus himself, and his followers, were known for a moderately ascetic lifestyle, eschewing the excesses of sensual gratification. (This makes it especially ironic that in modern English idiom "epicurean" often refers to foodie culture, a legacy of later misinterpretations and critics of the doctrine.)

For pleasure, as they conceived it, is not something you add up, cumulatively – rather, it is defined negatively, as the absence of pain. The term for this freedom from pain was ataraxia — literally, a state of not-being-shaken-up, a freedom from turbulence.

Preserving your ataraxia was a matter of balance. Should you drink some wine? Sure! – a little. Should you have sex? Yes! – some. If resisting these urges disturbs your mind, then satisfy them with moderation – there's no moral superstructure barring you from doing so. But don't overdo it, for it will shake you up, disrupting your ataraxia.

In certain ways Epicureanism is strikingly congenial to modern thought – it seems to foreshadow the physicalism that underlies modern science, and the pragmatic hedonism that characterises secular society. In my academic life, whenever I've asked students to the choose the school of philosophy they'd join, a majority of them have declared, "the pleasure one!"

But despite all that, we do not seem to be living in an age characterised by "freedom from turbulence". And nowhere is this more evident than in the context of our information culture, and in the chaotic maximalism of our digital experience. The very act of opening up a social media app, the sensory bombardment with which it confronts the mind, the cortisol spikes and calculated incitements toward further desire, are the perfect illustration of exactly what Epicureanism invites us to avoid.

Hence a radically Epicurean course would be to avoid the online world altogether – to completely eschew the extraneous stimulations of the body-mind that come with adding layers to your reality. This would be in keeping with what we're told of Epicurus himself, who spurned the life of the polis (the Greek city-state), with its rhetorical intrigues and social complexities. Instead, he dwelt with his followers in a community called the Garden. (Incidentally, the Garden seems to have been relatively unique among Hellenistic philosophical communities, in that it freely admitted female thinkers to its ranks, such as Themista, Leontion and Nikidion).

But there may be limits to the feasibility of totally unplugging. Most of us need to work, and this often involves operating in digital spaces with considerable regularity. And few can afford the real estate in which to establish an external Epicurean Garden of their own, from which to conduct their Zoom meetings.

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyWhat, then, are the best practices for true Digital Epicureanism? If we take seriously the conceit that virtuality will become more and more the substance of our lives, how can we go about cultivating Epicurean gardens in our digital spaces? How to dwell online in pleasure and peace?

There are existing theories and therapies that address this, such as apps that help manage screen time, and books with strategies for mitigating digital addictions. Neil Stephenson's Snow Crash, the sci-fi novel that produced the term "metaverse", also coined the term "informational hygiene", which has since come to refer to the discipline of keeping your search history, and therefore your mind, clear of digital disinformation. A related concept is technologist Clay Johnson's "information diet". Both of these terms, hygiene and diet, recall Epicurean ethical categories — hygieia (health) and diaita (habit, way of life) – and emphasise the physical-material impact that digital information has on our minds. Equally relevant is the "Digital Minimalism" articulated by the computer scientist Cal Newport, who urges that each of us need "a full-fledged philosophy of technology use, rooted in [our] deep values." Such a philosophy could conceivably be based on the hedonistic minimalism of the Epicureans.

But there is considerable variation in the degree to which one can control one's digital garden. For, unlike a regular garden where we simply choose what to include and exclude, the algorithms of online platforms create a feedback loop between our own curatorial choices and what gets presented to us in turn.

A TikTok "For You" page is a garden over which you both do and don't have control. If choosing to follow someone on Instagram is like selecting and planting a flower that you're consenting to see and smell on a daily basis, on TikTok, the flowers are cast unbidden at your gate, an atomic bombardment at the threshold of your perception – and the half-conscious milliseconds in which you hover or scroll are the microdecisions that prune and populate your informational experience. You may think you're the gardener, but it's equally the algorithm, and the garden is you!

This is where the materialist metaphysics of Epicurean thought becomes especially relevant. For, from such a perspective, you are matter experiencing itself, and in the realm of digital experience, you are specifically informational matter experiencing itself. Therefore the digital content you curate, and that which is curated for you, become the actual stuff of your mind – vestigia, as the Roman Epicurean poet Lucretius calls the material images that make up consciousness: "footprints" of the perceptions we have encountered, the content we have put into our brains.

And this is not just one-directional: it is not only a matter of what you put in, but what you put out. Every digital gesture – every comment, post, message – may be conceived as an addition to a garden that is shared. A provocative tweet, for example, may indeed merit a profusion of indignant @replies – but does that make the garden any better, or worse? There may be individual pleasure in sharing them, but the question would be whether that pleasure is sustainable for the digital environment. The Epicureans would have had little use for trolls, unlike the Cynics, who I wrote about in previous essay for BBC Future. (See: "Would Plato tweet? The Ancient Greek guide to social media")

Nathan Dufour Oglesby

Nathan Dufour OglesbyThe Epicurean ideal would be to make these additions with a maximum of care and intentionality, in order to maintain a minimum of psychic turbulence throughout the digital community. For even though they recognised no abstract moral injunction to "love thy neighbour" (or follower or friend), the Epicureans placed a high value on community.

In one surviving fragment of writing, Epicurus declares that friendship is a virtue in itself, though it originates in utility. The implication (elaborated further by Lucretius) is that we wouldn't have made it this far as a species if collaborative and communal care were not central to our operations. Mere aggregates of matter though we are, our evolution makes it evident that our fundamental existential orientation must be collaborative.

The question is not "online or offline?" but "community or not-community?" In other words, are we using digital spaces to connect with one another in the shared project of diminishing pain, or vainly attempting to escape reality and disconnect from ourselves?

Digital Epicureanism relieves us of the need to make moral judgments about whether virtual and augmented realities are "good" or "bad". It's not about moralising against the coming metaverse – which would be futile anyway. It's about recognising the material nature of all layers of reality, and connecting throughout them in a conscientious way – from the most "meta" layers of the virtual and digital, to the more fundamental layers of flesh, soil and matter itself.

Thinking in this way cultivates a relational understanding that is ultimately ecological, revealing insights into how we can interact healthily not only with other people, but also with the built and natural worlds. It provides the basis for an ecology of information, where we might cultivate collective awareness of the material costs of our information systems (the energy it takes to power the internet), as well as its psychological costs (a consideration which is also ultimately material). The injunction to exercise "informational hygiene" and keep a good "informational diet", is not only crucial for our mental health, but more vital than ever for the holistic functioning of the species and the planet.

Even though we may seem to be departing from physical groundedness into a strangely immaterial virtual lifestyle, we are in fact merely extending the web of relations that comprise our being. And we can let that very complexity invite us to be more aware of what we are made of – bits of matter-energy, coordinated in a relationship. In this attitude of Epicurean holism, we may derive a good deal of pleasure from our world, both on and off our screens.

--