How the world's deepest shipwreck was found

Caladan Oceanic

Caladan OceanicIn 1944, the USS Johnston sank after a battle against the world's largest battleship. More than 75 years later, her wreck was finally located, 6km (3.7 miles) below the waves.

On 23 October 1944, the first engagements of a gigantic naval battle began in Leyte Gulf, part of the Philippine Sea. It was the biggest in modern human history.

Over the following three days, more than 300 US warships faced off against some 70 Japanese vessels. The Americans had with them no fewer than 34 aircraft carriers – only slightly fewer than all the carriers in service around the world today – and some 1,500 aircraft. Their air fleet outnumbered the Japanese five to one.

Best of 2022

This article is part of BBC Future's "Best of 2022" collection, where we bring you some of our favourite stories from the past 12 months. Discover more of our picks here.

The battle had two major effects – it prevented the Japanese interfering with the American invasion of the Philippines (which had been captured by the Japanese nearly four years earlier) and effectively knocked the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) out of action for the rest of World War Two. Nearly 30 Japanese ships were sunk, and many of the remainder – including the biggest battleship ever built, the Yamato – would be so badly damaged they would be largely confined to port for the rest of the war.

While the wider battle largely saw the US outnumber the Japanese fleet, one crucial action was different. A small force – Task Force 77, mainly destroyers and unarmoured aircraft carriers – found itself battling a much larger Japanese formation.

The battle took place off the island of Samar. Massively outnumbered, the small US flotilla fought against overwhelming odds, pressing home their attack against the much larger and better-armed Japanese ships.

The US resistance was so fierce that it prompted the Japanese commander, Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, to turn his fleet around, believing he was now facing the bulk of the US forces. The small, relatively unarmoured American destroyers came as close as possible to the Japanese warships, preventing them using their powerful long-range guns. The small US force prevented a potential massacre, but their resistance came at a heavy cost. Five of the 13 US ships were sunk.

You might also like:

One of them was a destroyer called USS Johnston. Just after 07:00, Johnston was hit by shells from the Yamato, but fought for another two hours, peppering much larger enemy ships with shells and scaring off a flotilla of IJN destroyers trying to attack the lightly armed American aircraft carriers. It was only after two hours of fighting, with the ship hit by dozens of shells and its survivors clinging to the rear of the battered vessel, the ship finally sank, taking with it 186 of her 327 crew. Survivors reported one of the Japanese destroyer captains saluting as it slid beneath the waves.

But Johnston's story was not over.

***

Most of the world's shipwrecks are found in shallow coastal waters. Ships follow trade routes to ports, and coastal waters offer the chance of sanctuary if the weather turns nasty. So this is where most ships founder and sink. But the waters Johnston sank in are very different. Rather than a smooth decline, they instead drop steeply to great depths.

Samar Island sits on the edge of a vast marine canyon known as the Philippine Trench, which runs for some 820 miles (1,320km) along the Philippines and Indonesian coastline. It skirts around the eastern side of Samar Island, on the seaward side of Leyte Gulf. It is very, very deep. If you were to drop Mt Everest at the deepest point of the Philippine Trench, the Galathea Depth, its summit would still be more than a mile (1.6km) underwater.

Joemill Fordelis/Getty Images

Joemill Fordelis/Getty ImagesNo-one knows quite how long it took for USS Johnston to reach the ocean floor. It sank through layer after layer of the Philippine Sea, distinct stages which grow ever darker, colder and inhospitable. Past 100m (328ft) sunlight would have begun to fade. Past 200m (656ft) Johnston would have entered the twilight zone, a vast layer nearly a kilometre deep which marks the end of the effect of the Sun's light on the ocean. The temperature would have plummeted the further it sank. At 1,000m (3,280ft) Johnston's ruptured hull would have plunged through waters only a few degrees above freezing into what oceanographers call the Bathyal Zone, also known as the midnight zone.

No plants or phytoplankton grow here as the Sun's light cannot penetrate this far down. The water is freezing cold and this gloomy zone is sparsely inhabited by life. The animals that do live here have evolved to do so in cold and relentless dark. Eyes are useless, and so are fast-twitch muscle fibres, which elsewhere prey might rely upon to escape predators. But down here they consume too much energy to be worth it. The fish that live here look little like the ones that swim near the surface. They are soft and slippery to the touch. Some are blind and others almost transparent. What use are camouflaging scales when your predators – nightmarish creatures that hang suspended in the dark – have no eyes?

The average depth of the world's oceans is 3,688m (12,100ft), more than two miles deep. It is in waters as deep as this that the RMS Titanic sank on its ill-fated maiden voyage in 1912. But Johnston's death dive went far, far beyond this.

Past 4,000m (13,123ft) is the Abyssal Zone, with water temperatures hovering just above freezing and dissolved oxygen only about three-quarters that at the ocean surface. The pressure is so intense that most creatures cannot live here. Those that do differ from their shallow-water cousins in almost every way – fish have antifreeze in their blood to keep it flowing in the intense cold, while their cells contain special proteins that help them resist the intense water pressure that would otherwise crush them. But the ocean goes deeper still.

Drop further and there is the Hadal Zone, another layer found below 6,000m (19,685ft) from the surface. The Hadal Zone is found in the deepest ocean trenches, mostly in the Pacific Ocean, where giant tectonic plates push together far beneath the waves. Danish oceanographer Anton Frederik Bruun coined the term in 1950s, when technology had advanced enough for the first cautious exploration of these submarine chasms. The term hadal came from Hades, the Ancient Greek god of the underworld. It is in complete darkness, temperatures hover just about freezing, and the pressure is around 1,000 times that at sea level.

Finally, this is where the bottom of the Philippine Trench emerges. Many of the points measured along its length are around 10,000m (32,808ft or 6.2 miles) deep and at its lowest point reaches 10,540m (34,580ft) below sea level.

Xavier Desmier/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Xavier Desmier/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesSomewhere within this vast underwater trench, the USS Johnston finally came to rest. But the exact location was very difficult to predict. The ocean's surface is by no means featureless, but its anonymity can make finding the exact locations of naval battles a challenging task. There are no monuments, and no topographical features which aid identification. Underneath the waves, currents and tidal patterns can pull wrecks far from the spot where they sank.

It would be 75 years before human beings saw Johnston again. The first was Victor Vescovo.

Vescovo, 54, is a former US Navy intelligence officer turned private equity manager with a passion for exploring and oceanography. He has climbed Mt Everest and visited both the North and South Poles.

"I've been a hardcore mountain climber for 20-25 years, and when I'd pretty much done many of the things I wanted to do there, I was looking for a different challenge and I viewed it as a nice symmetrical thing to do, let's go to the deep oceans," he tells BBC Future from his home in Texas. "And it turned out that no-one had been to the bottom of all five of the world oceans. They'd never even been to the bottom of four of them."

Self-described as "technically minded", he believed the issue wasn't one of technology but of funding. "It'd be really expensive – but it is doable," he says. "So I cut the cheque, and got the team together, and for the next three years we designed and built the deepest-diving submersible in history that's able to do it repeatedly, which has never existed before, and then we took it around the world." Vescovo tested his new submarine, called Limiting Factor, by diving solo to the bottom of the Puerto Rico Trench – the deepest point in the Atlantic Ocean and two-thirds the depth of the deepest point in the world's oceans.

Early in 2020, Vescovo was taking part in a scientific mission with a Filipino oceanographer. They became the first people to dive to the bottom of the Philippine Trench. "It just so happened that a day north of there is the battlefield off Samar," he says. "I've been a 'military historian' since I was a small child and I was also in the US Navy for 20 years, so I knew a lot about the battle. I thought it would be an interesting attempt to try and find the wreck."

Mike Marsland/Getty Images

Mike Marsland/Getty ImagesVescovo's attempt wasn't the first – the story of Johnston had captivated many explorers and oceanographers over the decades. "The Vulcan Organisation had been going around the world finding World War Two wrecks for many years. But they were limited in their ability to go deeper than 6,000m (19,685ft), because they only use remotely operated vehicles. So, they actually found the wreckage of the Johnston – they were trying to find the deepest wreck as well – but they only found a portion of it and it was not really recognisable."

Finding the Johnston was made more challenging because a similar destroyer, USS Hoel, was also sunk in the same engagement. "They couldn't positively identify that it was the Johnston," Vescovo says. "And they couldn't go deeper. Their rated limit for their remotely operated vehicle was 6,000m (19,685ft). They could see that there was more debris down lower, so they pushed it down another 200m (656ft), risking it imploding, but they weren't able to see the majority of the wreckage."

The Vulcan's mission had almost proved where Johnston lay, but the crushing pressure of the deep Pacific Ocean had prevented them from settling any doubt. Vescovo believed his newly designed submarine might confirm it. While the Vulcan team did not share the location, Vescovo says "there were enough clues in the open source that I put my intelligence officer hat on and we were able to close in on where it probably was".

Vescovo and naval historian Parks Stephenson ventured beneath the waves in the submarine in the hope of coming across the wreck.

"He'd never actually done any sub diving before," says Vescovo. "I told him: 'Strange things happen down there.' The visibility is terrible, it's very confusing once you go down below 500m (640ft) or 1,000m (3,280ft), let alone 6,000m (19,685ft). And everything is harder. He was like, 'No, no, no I'm 99% convinced we are going to find it, it's here.' Sure enough, on our first dive we're down there for four hours and we find nothing."

A second dive also failed to reveal any sign of the wreckage, so they moved to a new location for their third dive. This time was more successful and they rediscovered the debris field that the Vulcan submersible had previously found.

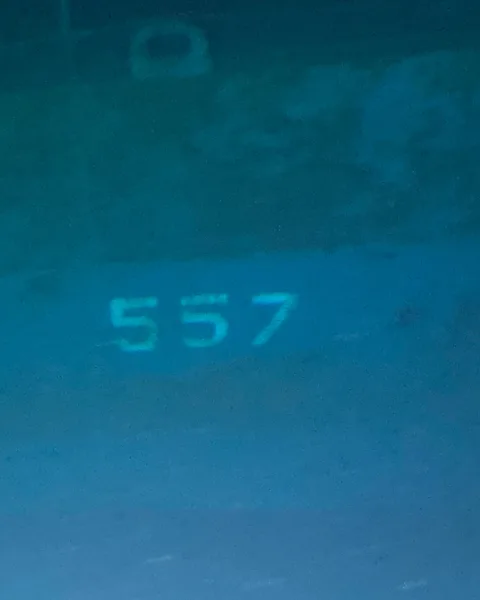

"With my submarine I was able to follow the trail of where the ship had gouged a V into the hillside underwater, and we followed it down another 500m (1,650ft) and that's when we found the front two-thirds of the ship in brilliant, intact form, with the [naval identification] number right there – 557. Positive identification."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJohnston's final resting place was more than 6km (3.7 miles) deep. "It's half again as deep as where the Titanic is – and that's pretty damn deep, that's 4,000m (13,123ft)," says Vescovo. "What was so interesting about this wreck, it was about as one-twentieth the size of the Titanic so it's a lot smaller."

The work required to find wrecks at such depths is deliberate and painstaking. "It's all about finding the so-called 'blood trail', finding a piece of wreckage and finding another one and then localising it," Vescovo says. "Because the ocean is really, really, really big and wrecks are very, very, very small."

Only a small fraction of the world's oceans plunge below 6,000m (19,685ft), so there has been little impetus to fund technology to explore them. Vescovo has other ideas. "Because I want to go deeper and look for things on the bottom, right now we're developing a sonar suite, side-looking sonar that actually can operate to 10,000m (32,808ft), it's never been developed before."

The new sonar suite, if it comes to pass, will allow Vescovo's submarine to make a map of the ocean floor in swathes up to 1.5km (one mile) wide "so we can actually do deep ocean searches for wrecks or anything else that's on the bottom of the ocean", the explorer says.

The first tests using this new side-looking sonar will take place in spring 2022 – off Samar Island. "We're going to use the Johnston," Vescovo says, "we're going to use the Johnston as a way to double-check the sonar to make sure it works properly, and then we're going to take it even deeper, where we are pretty sure the Gambier Bay, the Hoel and some of the Japanese wrecks are, even deeper. They could be in 8,000m (26,246ft), but no-one has any idea where they are, and we hope we're going to find them."

***

If you were to drop a pebble over the side of a boat above Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench – the deepest of the ocean's deepest places – it would take more than an hour for it to finally reach the bottom. "It takes us four-and-a-half," says Vescovo, "and the submarine is designed to go up and down fast! It's a long, long way down, and the environment there is just unbelievably harsh. When you go from sea level to outer space, you go from one atmosphere pressure to zero, it's a vacuum. When you go to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, you're going from one atmosphere to 1,100, immersed in salt water, and it's freezing cold. It is just torture for anything physical." One of Vescovo's biggest challenges was how to make sure everything from batteries to propulsion systems on the submarine would continue working at such crushing depths, dive after dive.

Corbis/Getty Images

Corbis/Getty ImagesLimiting Factor's missions to this inhospitable secret world have, little by little, helped grow the small club of humans who have seen the deepest point in the ocean. "Before we started our endeavour three years ago, only three people had been to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, and something like 12 people had walked on the surface of the Moon," he says. "We've now changed that – I've been able to take 15 people to the bottom of Challenger. Now, more people have been in space than have been to the bottom of Challenger, but we're trying to keep up," he adds.

Once the vessel has plunged beneath the choppy surface waters, "it's remarkably peaceful", says Vescovo. "At the surface, you're bobbing around but once you get under the water it gets really quiet, you just hear the whirr of the fans, and it gets dark pretty fast actually, at 500m (1,640ft) there's no sunlight. There's even no sense of motion, the sub can be gently spinning and you don't even realise it. And creatures stay away from the submarine, or you just don't see them because the portals are so small, so it's like you're in a little time machine, you're just sitting there.

"I'm monitoring everything, making sure things are going OK, but the passengers they wait until we get to the bottom. The joke we have is that when you're on the way down, a minute feels like five minutes because you want to get there and you're excited. When you get to the bottom a minute feels like a second because there's so much going on, you're looking outside, you're excited, and then a minute going up is like an hour, because you just want to get to the surface."

Monsters of the deep?

What life at great depth really looks like

At depths such as the one at which Johnston found itself, storytellers once imagined the realm of strange creatures, an inky-black monster's lair. But this frigid expanse is mostly – at least to the naked eye – devoid of life.

"People get a bit disappointed, they want the big scary monsters, they almost assume the deeper you go the bigger and scarier the monsters get, like Godzilla. It's actually the reverse. The deeper you go, the harsher the environment is, and large animals can't survive. Fish can't survive at full ocean depth. But what can survive is bacteria and microbes, which are no less important evolutionarily and biologically, and very small creatures like little shrimp. Some of them can absorb aluminium into their bodies to act as armour against the pressure. Or very small seaworms – things that don't make people go ooh or ahh, but they're extremely specialised, and from a scientific standpoint that makes them extremely interesting."

"I'm monitoring everything, making sure things are going OK, but the passengers they wait until we get to the bottom. The joke we have is that when you're on the way down, a minute feels like five minutes because you want to get there and you're excited. When you get to the bottom a minute feels like a second because there's so much going on, you're looking outside, you're excited, and then a minute going up is like an hour, because you just want to get to the surface."

Vescovo's missions to long-lost warships such as the Johnston follow a very simple rule: look but don't touch. "Any military wrecks remain the property of the country that they're from, regardless of where they are, so you cannot take anything from them unless you have their permission. Same with the Johnston. So we were very respectful, we did not touch the wreck, we did not take anything. But people also do not realise whether it's the Titanic or the Johnston, these wrecks are so deep and the saltwater so corrosive that there are no bodies, clothing isn't there, it disintegrates. It's an empty mausoleum that's more of a symbol of the people that died there."

But not all the descendants of those who have died want the last resting place of their relatives disturbed. The wrecks may be invisible, far below the ocean's surface, but the relatives of those who died sometimes have strong feelings.

Vescovo has encountered resistance before over plans to inspect another wreck, the infamous USS Indianapolis. Sent on a secret mission to deliver the first atomic bomb to a bomber base in the Northern Marianas, the Indianapolis was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and the 900 surviving crew members were left to drift for four days, with nearly 600 dying from dehydration, exposure or shark attack.

"I thought about diving [it] last year, but there was such an outcry from the veterans' families, they said they didn't want me to dive it, I said 'ok, fine I won't dive it'," says Vescovo. "They were very vocal about they didn't want me disturbing the wreck.

"The groups associated with all the wrecks seems to be different. For example, people were very supportive of my dive to the Johnston, maybe because it hadn't been identified, and the Indianapolis had been identified… but you just have to be respectful of their wishes, it was their family members who died. I'm not going to be an interloper and do what the heck I want and ignore everybody's wishes."

Caladan Oceanic

Caladan OceanicVescovo’s missions rely on a very specialised set of skills. "I have the certification as a submarine test pilot, which is something I don't think you really want to have, but when we were developing and building it, we did have a couple of situations where electronics failed or there was a puff of smoke in the capsule – which is decidedly not cool – but even in that case we had back-up systems and emergency action plans. I've never felt like my life was in danger.

"The most dangerous dive I've ever done was on the Titanic, and that's because the Titanic is very, very big, there are wires and there are ropes and there are cables. The biggest danger to a submersible is actually entanglement, and that happens around wrecks. Unlike when James Cameron dove the Titanic – he dove with two submersibles – I dove solo in one. If I got entangled, I was left to my own resources to get out. That can be a little tricky. And no-one can come get us."

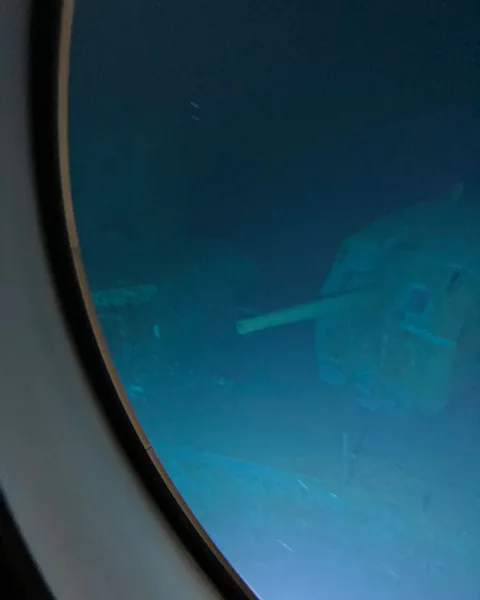

With no natural light, hazards only appear when they come into range of the sub's lights. "The Johnston actually gave me a little bit of a surprise," Vescovo says. "We went around her and at the very back end of her, she actually had a pretty large piece of metal about 15ft long, jutting out at a right angle, and when you're in a submersible you can't see that well. We're going around and I was like 'Holy ****' You don't know how sharp it is or the angle, and it's possible it could snare the submarine. That would be a bad day. I'm sure we could get out, we have a lot of power on the submarine and we can eject stuff off, but you don't ever, ever want to be in a situation where you're actually having to figure out a way to get off of something in a submersible when you're 6,000m 19,685ft) down."

The discovery showed that Johnston sank relatively intact, despite the enormous damage inflicted by the guns of the Japanese warships.

"Johnston was so deep, even deeper than the Titanic, there was less corrosion, less life on it, so it looked more pristine than Titanic did, it didn't have all the hanging stalactites, the rusticles. You could see the battle scars on the ship where the shells had come in and hit it, the guns were still trained to the right, the ship still looked like it was fighting."

Visiting deep wrecks such as the Johnston offers far more than just bragging rights though. It can also help piece together information that might be missing from the heat of battle.

"We are amateur historians, and while we read the histories and people think they know what happened in the battle, it's very confusing in battle, and what we say is steel doesn't lie," says Vescovo. By really closely investigating the shell holes, even the angle of the shells, we can have the wreck tell us a story of what happened. It's one more point of view of the battle. It's pretty irrefutable compared to human memory, which can get pretty confused. Already from the wreck we've discovered things that people didn't realise about the battle."

Vescovo's investigations, he believes, lend weight to the idea Johnston had been hit by Yamato, the largest battleship ever built. "It was the Yamato that actually delivered the first killing blows on her… why does anyone care? This was the largest battleship ever constructed by man, and it was taken on by a little American destroyer. It was David and Goliath. And the Yamato actually left – she chased her away."

Caladan Oceanic

Caladan OceanicThe giant naval battles waged across the world's oceans in the 20th Century are a rich world for explorers such as Vescovo to discover. "I'd love to find the Japanese wrecks from Midway," he says, referring to the four Japanese aircraft carriers sunk at a pivotal naval battle in 1942. "Those would be extraordinary to find because those are iconic ships of the Japanese navy, they hold a lot of pride for the Japanese people it would be nice to identify them."

There is another vessel on Vescovo's list too: the Yamato herself. In April 1945 the gigantic ship was ordered on a one-way mission to disrupt the American landings on the island of Okinawa. Yamato's commander had been told to beach the ship and use it to bombard the America invasion. Surprised by a huge fleet of American aircraft, it was sunk with the loss of more than 3,000 lives. "She actually only lies in about 300 (984ft) or 350m (1,148ft) of water," says Vescovo. "It has been visited, at least by a robot, but I don't know if it's been visited by human before. Now, I would be extremely sensitive about that, because it's such an important wreck for the Japanese people. I would never even attempt to dive that wreck without their assent, their involvement."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe ocean explorer Sylvia Earle has been a prominent advocate for further exploration of our hidden undersea world, saying to NPR in 2012 that "we haven't made the investment in understanding what's there. Only about 5% has even been seen, let alone explored". Vescovo is a similar enthusiast, especially for those very deep places that have remained hidden from human eyes.

"Those have huge implications for marine biology, marine virology but also geology, looking at the rocks and plate tectonics and all that," he says. "And then there's just mapping – 80% of the ocean seafloor is unmapped, and we want to go and run around and map those just because that's something that should be done.

"The beauty of the ocean is because it's so unexplored, it's like a tragedy of riches. Where do you want to go now? Anywhere you go is going to be new. Where do you start?"

* Stephen Dowling is BBC Future’s deputy editor. He tweets at @kosmofoto

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List" – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.