The eccentric dog breeds that vanished

Alamy

AlamyFrom a vegetarian dog to a walking piece of kitchen equipment, the world was once home to an abundance of strange and ancient hounds. Where have they gone – and could we bring them back?

In a particularly hilly corner of South Wales, somewhere within the half-ruined walls of a Norman castle, you'll find the last remaining member of a long-vanished lineage – a dog named Whisky. With her sausage body and stumpy little legs, at first glance, she could be an exotic variety of dachshund. But look closer and you'll start to notice certain oddities.

The little dog's russet fur is silky-yet-scruffy, rather like a Yorkshire Terrier's. Meanwhile, her tail is a perky curled tuft, as they are in Pomeranians. Her face is different, too – with an upturned nose and Spaniel-like ears cropped short against her head, evoking the bowl haircuts of the generations of medieval lords who inhabited the fortress before her. Her beady little eyes always have a somewhat glazed expression.

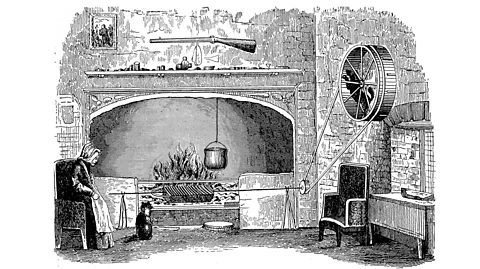

The last feature is not surprising, because Whisky is, in fact, a taxidermy "turnspit" dog – the final relic of an ancient breed that died out in the Victorian era. She once worked in the kitchen of a nearby country manor, where she would have spent many of her waking hours waddling along in a kind of giant hamster wheel, suspended on the wall above a fire. This was connected to a roasting spit via a system of pulleys, so that as one spun round, it turned the other. Turnspit dogs were exactly what they sound like: compact hounds specifically bred to run for hours on end, powering a roasting spit as they went.

The turnspit's backstory may seem ludicrous by modern standards, but there are arguably still plenty of dogs in existence today that could compete with its eccentricity.

The World Canine Organisation officially recognises around 370 different breeds, including the fashion-victim Chinese Crested, with its nude, greyish body accessorised with tufts of long blonde fur; the Puli – essentially a living mop, with its full coat of long dreadlocks – and the aspiring lion, the Tibetan Mastiff, famous for its massive size and long golden mane.

The thing is, there used to be more – many, many more.

For centuries, the world was home to a kaleidoscopic array of outlandish dogs – some of which were so bizarre, they sound made-up. In Hawaii, there was the Poi, which only ate vegetables and was treated more like a goat than a relative of wolves. Meanwhile, in the Pacific Northwest, there was the woolly Salish, a literal sheepdog bred for its wool, which was turned into clothes.

Alamy

AlamyDespite their charisma and past popularity, these breeds are now no more than ghosts, faded memories cobbled together from stories, written records and a scattering of specimens in museums.

Even the Talbot, the archetypal dog from the Middle Ages, often depicted on coats of arms; the Chien-gris, beloved of the French nobility, and at one time considered the only dog worthy of inclusion in royal hunting parties; and the menacing lion-fighting Molossian, favourite of the ancient Greeks, simply couldn't survive the whims of capricious human taste.

Where did these eccentric dog breeds come from? Why did we abandon them? And could some of them still be with us, hiding in plain sight?

You might also like:

An innovation

Today the concept of a breed is well-established, defined as a collection of dogs with a certain set of characteristics, that – except for the occasional lapse – generally only reproduce with others within their group. But this is a relatively new development.

For millennia, there were no official breeds, stud books, or careful programmes of selection. Instead, dogs were often categorised according to their function – such as "dog for hunting deer" or "lapdog" – as well as the place they originated.

"The word they [often] used was 'types'," says Michael Worboys, emeritus professor at the centre for history of science, technology and medicine at the University of Manchester. "But people had all sorts of names of the different types of dogs. They talked about varieties, they talked about strains…"

While dogs would usually be bred with others from within their type, no one was really keeping track – and consequently, these groups were significantly looser categories than they are in the 21st Century. "They were like the colours of a rainbow," says Worboys. "They kind of bled into one another. So there were greyhounds, but they kind of merged into foxhounds, which did a different type of work."

Take Alexander the Great's favourite dog, Peritas, who he raised from a puppy.

It's thought the dog was a Greek or Macedonian variety, possibly a Laconian Hound – a massive, athletic dog mostly used for hunting deer and hares. They were famed throughout the ancient world, and widely depicted in classical sculptures, mosaics, gravestones and drinking cups. With their wolfish faces, long snouts and "sparkling eyes", they resembled modern greyhounds, but sources disagree about their other defining characteristics.

Alamy

AlamyWhile some ancient writers described the type as masterful runners – they were also known as "swift Laconians" – other sources wrote that they were slow and mostly relied on their sense of smell to catch their prey. Regardless of their skillset, Alexander the Great reportedly loved his so much, he named an Indian city in Peritas' honour when he died (though this was something of a habit – he also named one after his horse, Bucephalus).

But this all changed with the invention of the dog show in the mid-19th Century. As Worboys wrote in his book, The Invention of the Modern Dog, co-written with the historians Julie-Marie and Neil Pemberton, the Victorians took the rough types that existed at the time and polished them into breeds with clearly defined traits.

"The goal was to get a uniform-looking population," says Worboys. "It was a bit like creating standardised nuts and bolts, or time. Dogs were in a sense kind of mirroring of what was happening with industry. They drew up standards and bred to those standards, so a spaniel would look the same everywhere."

One dog that personifies this trend is the Newfoundland, which originally hails from the eastern Canadian province of the same name – a frigid, coastal region where parts have a polar or subantarctic climate. With their fluffy, bear-like appearance, the type became a popular pet in 18th Century Britain, particularly among the upper classes.

Lord Byron acquired one when he was 15, who he named Boatswain. After the animal's death the poet buried him in an enormous marble tomb, on which he inscribed a eulogy, Epitaph to a Dog. "…Whose honest heart is still his Masters own, Who labours, fights, lives, breathes for him alone…"

"They [the early Victorians] liked them because they were thought to be noble, lifesaving dogs. What was important about them was their character," says Worboys. At the time, they had a varied look – with dogs in all different shades of black and white.

But once breeds were invented some decades later, suddenly the Newfoundland's aesthetic was in the spotlight. "The Labrador [once just lumped in with other Newfoundland dogs] became standardised," says Worboys. "The Victorians decided it could be black – all black – with a standard kind of shape, or a black and white variety that they gave a different name to."

According to Worboys, this standardisation was one major reason for a surprising, hidden event that occurred during the Victorian era. "What there's general agreement around is what population geneticists call a bottleneck," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter more than 30,000 years by the side of their human companions, and the development of hundreds of different types, all around the globe – for different climates, hobbies, tastes, and professions – dogs were suddenly at the mercy of shows and sporting events.

"There are a number of dogs that the Victorians kind of abandoned," says Worboys. "If dogs don't get a following in a dog show, then they kind of disappear. Nobody breeds them, nobody buys them, nobody shows them." The era saw a kind of mass extinction of dogs which had been in existence for millennia.

Today, almost every surviving dog breed once ran the gauntlet of this bottleneck – and is descended from the small number that catered for the fads and peculiar tastes in that era. As a result, much of the genetic diversity once found in dogs has vanished forever.

But shows are just one of many reasons so many dogs have disappeared in the last few centuries.

An unfortunate friend

For much of the 17th Century, the scurrying, yapping forms of turnspit dogs could be found in almost every large house in England, churning out meat to feed hoards of knights or other important visitors. It was a wretched life – the unfortunate pooches were considered coarse, vulgar, and hideously ugly, and habitual cruelty towards them was common.

In the colourful and occasionally mocking book Anecdotes of Dogs from 1846 (which, among other things, suggests that "The souls of deceased bailiffs and common constables are in the bodies of setting dogs and pointers"), the English writer Edward Jesse wrote that, in his youth, "as they are said to be at present, [cooks] were very cross, and if the poor animal, wearied with having a larger joint than usual to turn, stopped for a moment, the voice of the cook might be heard berating him in no very gentle terms."

To drive home the sheer horror of the role – which involved toiling away in the almost-unbearable heat of a fire, in a kitchen choked with smoke, for hours at a time – Jesse also relates an anecdote about a group of turnspit dogs in the city of Bath which liked to congregate in the church during services to relax. One day, when the word "spit" happened to come up in a sermon, they all dashed out of the room, thinking they were about to be asked to go to work.

But at the turn of the 19th Century, the invention of mechanical spit-turners changed everything. Rejected as pets and no longer useful as kitchen staff, the dogs abruptly vanished – going almost completely extinct as early as 1807, with their final demise some decades later. After a lifetime of service, Whisky ended up as a stuffed specimen on display in a shop. She was gifted to Abergavenny Castle in 1959, where she currently resides in an 18th Century hunting lodge.

Alamy

AlamyWhen a particular dog type was no longer needed, the final reckoning could be swift.

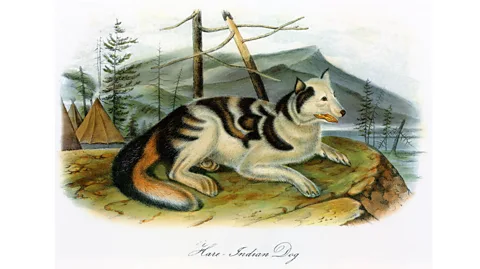

This is precisely the fate that may have befallen the Hawaiian Poi, too – a small, Jack Russell-like dog native to the South Pacific. Coincidentally, they're thought to have resembled the turnspit, and like these distant cousins, some sources considered them ugly.

Polynesians formed strong bonds with their Poi dogs, fiercely defending them from harm, burying them alongside humans, and – based on a couple of European accounts about their treatment of dogs generally – possibly breastfeeding some puppies.

However, "descriptions from European visitors were not particularly kind," says Carys Williams, a research officer at the Dogs Trust, UK, who has studied the Poi. "They were used to bringing collies and very utilitarian dogs with them on their trips, and then they've launched on these islands and found these small, scrawny dogs with bandy legs… and they just weren't much of a sight to look at."

The fact that the Poi couldn’t bark probably didn’t help their image. "…these animals can only whine and yelp, and this they do in the most piteous tones imaginable," wrote one explorer in 1880, as Williams notes in a paper she authored on the subject.

Genetic evidence suggests that the Poi were close relatives of the dingo, and descended from dogs brought to the islands tens of thousands of years ago. The dogs have been kept by the islanders as pets for centuries, despite, as Williams explains, the near-total absence of a functional role for them, either in hunting, guarding (there are no large predators on the islands to defend against), transportation (the islands are too small for this to be necessary), or herding (the locals mostly kept pigs).

That is, except one job – as food. The Poi was bred as a companion and also, jarringly, eaten, though usually only as part of a ceremonial feast. When a dog was killed, its fur could be incorporated into clothes and its teeth made into jewellery (one museum in Honolulu has 13 ankle rattles in its collection that would have collectively required 11,218 teeth from 2,805 dogs to make, according to Williams' research).

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about the dogs is that they were mostly vegetarian. Indeed, the word Poi comes from the Hawaiian dish of the same name, a staple food traditionally made by mashing cooked taro roots on a wooden pounding board until it achieves a paste-like consistency. Along with occasional scraps, this formed the basis of the hounds' diet.

Alamy

Alamy"The vegetarian diet was much more of a human choice rather than for the dogs," says Williams, who explains that there are hints the dogs were nutritionally deficient. An analysis of skeletons found on archaeological sites has revealed dental cavities and signs of jaw atrophy, possibly from the starchy taro and absence of the need to chew their food.

However, after millennia at the heart of Polynesian culture, eventually the Poi fell out of favour. Western colonists brought over their own dogs to places like Hawaii – and as they interbred, native ones began to disappear. At the same time, these new settlers led to a change in attitudes, until it was no longer considered acceptable to eat your pet. The last Poi lived in the mid-late 19th Century – and there are no surviving paintings, photographs or other artworks that can be definitively linked to them.

"It [the Poi] would probably be very suited to modern life, to be perfectly honest, a very agreeable dog very low levels of aggression," says Williams.

This wouldn't be the first time colonialism and a loss of functionality have conspired to wipe out an ancient type. Another classic example is the Salish woolly dog, which has historically played an important role in the culture of people from the Coast Salish indigenous group in the Pacific Northwest of Canada. These fluffy, floppy-eared hounds were always white, and their soft wool was regularly combed, so that whatever came off could be woven into blankets.

However, they weren't just canine sheep. Woolly dogs were treated with respect, and reigned over people's houses where they were cosseted and adored. Like other dogs, such as those used for hunting, they were considered to be somewhere between animal and human – and consequently, they were often given names and buried.

As with the Poi, the woolly dog's demise accompanied a major lifestyle shift that was brought about by the arrival of Western settlers. "It was partly because other kinds of material were available," says Dana Lepofsky, a professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University, who has studied the dogs. "But also because the whole weaving culture the social context of that changed with colonisation."

A possible revival

But the intermixing between modern "breeds" and ancient "types" raises a tantalising possibility – could there be Poi in existence today, disguised as ordinary dogs?

Alamy

AlamyThis idea is what led the animal curator Jack Throp to attempt a de-extinction at Honolulu zoo in the 1960s. By breeding dogs with Poi-like characteristics together, and then doing the same with several generations of their offspring, he hoped to concentrate the type's genes until it emerged from the ether of hybridisation.

"There's a wonderful picture in the Honolulu Star where he's recreated what he thinks a Poi dog should look like," says Williams. Unfortunately, the project's results are not well-documented, and not long afterwards the project seems to have died. "And again, it never really picked up traction as a popular breed and people wanting to preserve them," adds Williams.

However, there might be more of an afterlife for the Salish dogs, which ethnographic studies suggest were sometimes intentionally crossed with wolves and coyotes to make them better hunters. Kasia Anza-Burgess, a former archaeologist who has studied the Salish people and their relationship with dogs, is optimistic that perhaps their lineage lives on somewhere in the wild.

"We didn't find any genetic evidence [of hybridisation] in our sample [of Salish dog bones from archaeological sites]," says Anza-Burgess. But she points out that she only looked at mitochondrial DNA, which is passed from mothers to their offspring. This is significant, because – naturally – it was the female dogs that Salish people would let out to breed with wolves or coyotes, so injections of wild genes would always come from males.

"But I think it would be fascinating for future research to look at whole genomes and not just the maternal lineage, and see what kind of backcrossing you can find there, because the evidence seems pretty strong that it should be there – we just didn't pick it up," says Anza-Burgess.

A tricky decision

Fast-forward to today, and endangered dogs face a new obstacle on the path to survival: the collision of genetics with ethics.

In the last decade, growing awareness about low genetic diversity in many dog breeds – particularly pedigree varieties – has led dog organisations to take inbreeding more seriously.

Today some breeds have such small populations that the ethics of keeping them going becomes tricky – with such low genetic diversity, they can become more susceptible to deformities or illness. Eventually, "inbreeding depression" – where a population's fertility is affected by the accumulation of unhealthy genetic variants – can wipe them out altogether.

One breed at risk is the Sealyham terrier, which became fashionable among celebrities in the 1930s and 40s – Cary Grant, Princess Margaret, Marlena Dietrich, Elizabeth Taylor, Bette Davis and even Agatha Christie all had one of these cuddly white dogs at one time. With their curly white fur and venerable beards, the dogs seem almost part-lamb, part old man.

But after decades of popularity, they fell into decline with the emergence of designer breeds like the cockapoo – the offspring of a poodle and a cocker spaniel – which has similarly cuddly features.

After hitting rock bottom in 2008, today their populations are steadily increasing. However, the entire breeding population is still only just over 100 – often considered the lower limit for the survival of endangered species.

Given the new focus on the genetic health of dogs, Worboys doesn’t think there's much hope for endangered breeds like the Sealyham today. He recalls a conversation with a vet at a kennel club a few years ago, "and he was saying, off the record, there are about six or seven breeds he wished would disappear because they're more trouble than they're worth".

Who knows, perhaps soon such delightful hounds as the Old English Sheepdog, the Sealyham Terrier, and the Irish Wolfhound could join the list of extinct historical curiosities, along with all the others.

--

Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett

--