The hidden history behind our pets' most revolting habits

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom pooing in strangers' gardens to barking incessantly, even the most precious pets can be annoying, embarrassing, or just plain revolting. Where did these behaviours come from?

In a leafy suburban corner of south-east London, a war is brewing.

It started in May this year, when one of my neighbours took a sudden interest in the little wilderness at the front of his house. Over the next three weeks, he could regularly be seen labouring away, hacking out weeds, smoothing the soil, and adding compost. Then one day, it was time to add the finishing touch – a soft carpet of pristine turf. The result was as neat and carefully manicured as the green slopes around Windsor Castle. I remember wondering what the local cats would make of it.

The first night brought a swift, decisive answer. Once as flat as a snooker table, the next day the lawn's surface was ridged and twisted, as though the turf rolls were tectonic plates that had been pushed against each other. It was scattered with little brown curls of cat poo.

Undeterred, my neighbour put the garden back together and stayed up every night for a week, to ward off any more marauding felines. But it happened again – and again, and again. As I type, his fortifications have escalated to almost ludicrous proportions. The lawn's entire surface is now sheathed in protective netting, and there are little pots of vinegar at each corner, which cats supposedly detest. The final insurance is an ultrasonic cat scarer, which blasts out unpleasant sounds in a range that they're particularly sensitive to. So far, the defences are holding up – but who knows how this battle could end. (I might suggest a moat.)

As it happens, gangs of defecating cats look set to become a lot more common. In the UK, the most fashionable pets are now collectively almost a third as populous as humans, with an estimated 10.1 million dogs, 10.9 million cats and one million rabbits. Likewise, worldwide pet ownership is booming – in Japan, businesses have embraced the new trend by launching dog clothing lines and cat hotels, leading some commentators to suggest they're replacing children. In the US, there are almost 78 million dogs and 58 million cats.

Alamy

AlamyBut as more and more pets have bounded into our homes and slunk onto our laps, some of these precious new family members' less desirable habits have become more apparent. There's the incessant barking and meowing that can keep whole neighbourhoods awake, digging up of plants, jumping up with scratchy claws, chewing of wires, and – apologies for so many nauseating poo references – enthusiastic consumption of other animals' faeces.

(The latter is regrettably normal. One dog in my acquaintance, an elegant chocolate-brown greyhound called Buddy, races into his garden each morning to snaffle up any delicacies left for him the night before by the local foxes. If his guardian turns her back for a second while they're out walking, he'll locate and ingest several reeking deposits. At BBC Future we feel that this tantalisingly disgusting fact deserves its own piece, so we'll cover this one in more detail later in this series.)

Where did companion animals – whose behaviour is often so carefully aligned with human preferences that dogs have evolved a dedicated muscle in their eyes to make them cuter, and cats have learned to interpret our facial movements – get those habits that are annoying, disturbing, or just plain revolting? And how can we learn to live with them?

To trace the origins of any particular behaviour, there are two important factors to consider – the wild animal your pet evolved from, and its history of living with humans.

Jumping up

The closest living relative of dogs (Canis familiaris) is the grey wolf (Canis lupus), which is native to Eurasia and North America. However, it's thought that dogs are not their direct descendants – one genetic analysis revealed that modern dogs are equally closely related to wolf populations from several different parts of the world, suggesting that they all evolved from a common ancestor instead.

This mysterious, now-extinct wolf species might have lived in Siberia approximately 23,000 years ago, and been thrown together with small, isolated groups of hunter-gatherers by the frigid conditions of the last ice age, when much of North America, Northern Europe, and Asia was frozen over.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt first, perhaps the wolves merely followed humans around, snapping up discarded scraps of food as they moved from camp to camp – or they may have hunted in packs alongside humans, chasing down large prey and providing such an advantage that they allowed us to out-compete our close relatives, the Neanderthals. Another possibility is that it all began with ancient humans keeping wolf pups as pets.

Eventually the relationship deepened and the wolves underwent a physical transformation – their ears became floppy, their tails curved, and their coats became mottled. (An eccentric 62-year experiment in Russia, in which foxes were selectively bred until they had no fear of humans, has revealed that these are common side-effects of evolving tameness.) They also adapted their behaviours to suit their new collaborators – in some cases, exaggerating traits already found in their wild ancestors, and in others, inventing brand new ones. To find out which is which, all you have to do is compare dogs with modern-day wolves.

You might also like:

Take the excitable greetings of many dogs, who jump up and try to lick your face, eventually settling for whichever part of the body doesn't recoil quickly enough. "They would like to give a 'kiss' – or at least this is how people describe it," says Zsofia Viranyi, an expert in comparative cognition at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, and co-founder and co-director of the Wolf Science Centre.

In fact, this trait – often ranked high among dogs' most annoying habits – is a quintessential wolf behaviour – a relic from their ancestors tens of thousands of years ago.

As pups, wolves routinely jump up and lick inside other pack members' mouths after they have returned from a hunt, as a way of begging for food. Just like penguins in the Antarctic, the adult wolves will promptly vomit up a half-digested meal for them to eat.

"And then the older animals also keep the behaviour and they use it for greeting basically," says Viranyi, who explains that it generally involves lower-ranking individuals licking the mouths of those with higher status. "So basically, whenever the pack comes together, and they want to do something together, or when somebody was away and then returned," says Viranyi.

If you let them, wolves will also do this with humans. "Some people who raise wolves will actually kiss them," says David Mech, a senior research scientist with the US Geological Survey who has studied wolves for decades. "I knew one guy that basically French kissed his wolf." Thankfully dogs seem to have dialled it down a bit.

Alamy

AlamyBarking and meowing

On the other hand, some habits that are perfectly normal in the wild ancestors of our pets have been greatly exaggerated.

Like dogs, cats have also been living with humans for millennia. They're descended from North African/South-west Asian wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica) – solitary, territorial animals that primarily feed on small rodents. Genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that they may have originally encountered humans in the famous Fertile Crescent region of the Middle East at least 6,500 years ago, where the first farming communities sprung up. (Other than domesticating cats and pioneering farming, the people in these settlements also invented the earliest writing systems and the wheel.)

Initially, the cats hung around for the banquet of rodents that thrived around human settlements, but eventually they began to interact more and more with people – and ended up as unlikely candidates for domestication. They dispersed from their homeland along human trade routes, first spreading to Europe and Africa, where they made their way into ancient Egyptian religions – the goddess Bastet was often depicted as a cat – pyramids and hieroglyphs, and interbred with local North African wildcats.

Which brings us to a trait that some cat owners might consider an inherent part of their appeal – while others feel compelled to desperately search "how do you get a cat to shut up?" at three in the morning: the meow. Intriguingly, wildcats do meow – but only at their mothers when they are kittens. As adults, they don't generally make this noise.

Domestic pusses keep their meow throughout their lives, but not for the benefit of communicating with other cats either – just their human companions. Back in 2004, scientists asked human listeners to rate the pleasantness of meows from domestic cats and their wild counterparts, and found that the former are significantly more pleasant to hear than the latter. This suggests that not only are their "annoying" vocalisations an adaptation to life around humans, but that they've already been mellowed by domestication.

Alamy

AlamyIt's a similar story for the dog's bark.

Contrary to popular belief, barking is not just for dogs – wolves invented it first. "It's not as sharp bark as dogs make – it's rougher and more guttural, but anyone listening to it would say yes that's a bark," says Mech. However, while wolves tend to bark as a warning or sign of aggression, domestic dogs use it as a universal language to convey a broad spectrum of remarks, from the original meanings to "hello", an invitation to play, excitement at an impending snack or walk, or loneliness.

It's not known exactly why ancient wolves abandoned their eerie howls altogether and switched to barking full-time, but there are some hints. One 2019 study found that the most annoying dog barks have unique acoustic signatures – they're high pitched and atonal, similar to the meows of cats and the cries of human babies. The authors explain that dogs may have adapted certain kinds of barks to evoke a strong reaction from humans, and provoke them into taking action.

Barking has also historically been helpful to humans, who have used dogs to hunt, herd animals and defend their property. A 2004 study found that moose hunters in Finland who bought a dog with them were 56% more successful, possibly because dogs often bark at their victim until they stop moving – allowing their human collaborator to sneak within killing range. This makes sense, since dog breeds developed for hunting tend to bark the most.

Ironically, barking is the cause for one of the most common complaints about dogs. A 2015 study of South Korean owners found that 47.1% reported excessive barking, while a 2012 survey of New Zealanders found that they ranked barking as more irritating than other urban noises.

Gifts, poos and plants

Despite the adaptive meowing of modern pusses, some experts only view cats as "semidomesticated", since they retain many of their wild behaviours and readily interbreed with wildcats – so much so, that they have rendered some wild populations (such as Scottish wildcats) functionally extinct. As a result, to find out why your cat brings you gifts, poos on your neighbour's lawn, or digs up your plants – look no further than the wildcat.

In their wild cousins, depositing faeces in conspicuous places is an important method for marking one's territory. James Serpell, professor of ethics and animal welfare at the University of Pennsylvania's School of Veterinary Medicine thinks this might explain the issue of domestic cats pooing in the neighbour's garden. "They tend to target areas on the edge of the territory," he says. "When they're leaving it around the place they're saying, 'okay, you are now entering my domain'." So if you own cats, you might even be less likely to find their faeces in your garden than if they belong to your neighbours.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnother factor is that wildcats are particularly fond of toileting on soft soil that has recently been turned. "That's a very nice substrate for them – if you have a well cared for garden with lots of nicely turned loose soil around, then that's going to be a magnet for cats," says Serpell. He explains that cats probably don't dig up plants – or freshly-laid turf – on purpose, but in addition to defecating in conspicuous locations, they also sometimes instinctively bury their faeces.

It's thought that the "gift"-giving tradition among domestic cats might have originated in wildcats, too.

Unlike lions, which have been estimated to kill 15 large animals each year, wildcats evolved to eat tens of small mammalian prey per day – they are naturally prolific killers, with fastidious dietary requirements that mean they need a varied diet. Domestic cats haven't adapted to eat human scraps in the same way dogs have – they can't taste carbohydrates – so retaining their hunting skills may have been a sensible strategy for supplementing their nutritional intake.

Before the advent of pet food science (Read more about why processed pet foods are so addictive), refrigeration and the wide availability of affordable meat, cats that could hunt probably had a survival advantage. In fact, while modern-day domestic cats rarely eat the creatures they bring home, it's thought that they were an important food source for historical cats – and modern strays spend more time hunting than those with definitive homes.

Oddly, bringing back a catch and depositing it at your feet is may also be a wildcat behaviour. In the wild, mothers naturally bring half-dead animals back to their nest, for their babies to practise hunting on. Some experts think that the "gift"-giving of domestic cats is an extension of this trait – they're either instinctively bringing their catches back to where they live, or they think of you as a particularly inept kitten that needs to learn how to hunt.

Chewing wires

Of course, other kinds of pets can be just as hard to live with.

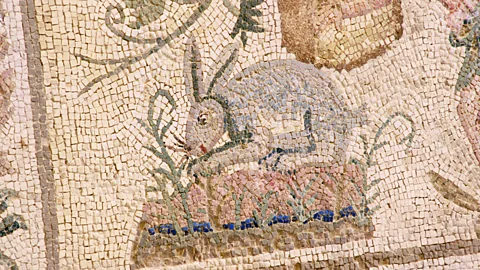

After cats and dogs, guinea pigs and rabbits are among the most numerous pets. There are around 400,000 of the former in the UK alone, and according to current estimates they were domesticated even earlier than cats. These small, squeaky mammals have been eaten in South America for almost 10,000 years and were first domesticated by the Inca civilisation up to 8,000 years ago, before their wild ancestors went extinct.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe history of keeping rabbits is also ancient. In 2019, scientists identified a previously overlooked bone found at a Roman palace in Sussex as belonging to a rabbit from the 1st Century. An analysis of its bones suggested that it had been kept in captivity and may have been a pet. The first domesticated individuals are thought to have come around 400 years later, raised by French monks. This remained their primary use for centuries, until the Victorians bred them into the array of ultra-cute, slightly ridiculous companions we're familiar with today.

Other small pets such as rats, hamsters, mice and gerbils are more recent still, domesticated over the last few hundred years via intensive selective breeding, sometimes just from a few individuals. Like cats and dogs, these animals have clung on to certain natural behaviours – souvenirs from their evolutionary past.

One of the most common complaints on the tongue-in-cheek social media group "Bunnies are Arseholes" is how fond rabbits are of chewing interior furnishings, including wallpaper, carpets, sofas (I once woke up to find that my floppy-eared flatmate had eaten a neat, round hole in the middle of mine), skirting boards, chair legs – you get the idea. But by far the most sought-after delicacy seems to be wires. Any wires that happen to cross their path – laptop cables, headphone sets, oven cords – will be snipped more quickly than you can say "I wonder where I put my…"

The problem is also common among other small mammals, especially guinea pigs and rodents. The insurance sector often attributes around 25% of all electrical fires in buildings to wild mice and rats, which can gnaw away at wire insulation – exposing raw wire which may lead to sparks or a short-circuit. But why do they do it?

According to Serpell, there are two reasons for this.

One is that in the wild, these prey animals spend inordinate amounts of time planning escape routes to and from their homes – they like to have multiple exits from any given location, and keep paths clear so that they can race to safety if a predator turns up. "If they find a wire crossing their path, the natural tendency is to see it as an obstruction," says Serpell. "They chew it in order to get rid of it as they would, say, a stick that was in their path in the wild."

Alamy

AlamyThe other is that these small mammalian pets will chew everything, regardless of what it's made of. Many species have teeth that grow continually, and must be worn down in case they get too long.

It's less common for dogs and cats to chew wires, but when they do, it's often because they're bored or enjoy the interesting texture in their mouth. It's also natural for many animals to chew on things instinctively as a way of exploring them.

But despite these frequent complaints, Serpell thinks our pets are overwhelmingly well-adapted to life with humans. "The thing that stands out for me is how few major behaviour problems they have, which is a testament to how well they've managed to adapt to requirements," he says. If you're not convinced, he points out that living with a wildcat or wolf would be significantly more problematic.

In fact, it seems that many of the so-called annoying habits that our pets have are just adaptations to humans.

"[Pet] animals are just like humans actually, we carry out a whole evolutionary history with us," says Viranyi, who points out that our requirements have been changing so fast, it's hard for them to keep up. "Moving the animals into this artificial urban environment – we live under circumstances that are different to the ones they evolved in." Historically, these behaviours were useful, but things have now changed and we've decided we don't want them.

One example is the border collie, which was first bred at the Anglo-Scottish border for herding sheep. "They have an inexhaustible appetite for this," says Serpell. "And if you don't give them sheep to herd, they'll find other things to do, which can be extremely disruptive in a kind of urban or suburban family context." Urban border collies might try to herd children or develop obsessive fetching behaviours – they're well-adapted to what they were bred for, but it can be difficult to keep them occupied if that's not what you want from them.

"So there's all sorts of sort of ramifications when we take these animals that we've selected particular types of behaviour for many generations, and then we basically arbitrarily decide at some point that we no longer want them to do that anymore," says Serpell.

For more minor annoyances, understanding where our pets' habits come from might help us to reframe them as what they are – fascinating ghosts from the past, rather than personality flaws to be eradicated.

Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.