The mystery viruses far worse than flu

Alamy

AlamySpanish flu was one of the most serious pandemics humanity has faced over the last century. But there are others, and some have the capacity to be even deadlier.

It arrived with the army of England’s new king. Just days earlier, tens of thousands of men had been fighting for their lives on a marshy field in Bosworth, Leicestershire. There, in the summer of 1485, the bitter rivalry between Henry Tudor and Richard III was finally resolved – with Richard III dying at the Battle of Bosworth Field.

Freshly styled as Henry VII, the victor led his troops on to London. Little did he know that there they would be about to face a very different kind of mortal peril.

The first sign was a feeling of general apprehension, which soon led to shivers, pains, and headaches. Then the perspiration set in. The victims would be swamped by a torrent of sweat, which led to insatiable thirst and delirium. Finally, they’d feel an overwhelming urge to sleep. If they succumbed, they’d likely end up dead. The fatality rate was up to 50%.

You might also like:

The army had brought with them a strange and unknown disease. Dubbed “The English Sweat”, this alarming malady swept across the city, killing 15,000 people in just six weeks. Eventually the epidemic fizzled out, but not before it had spread to Europe, leaving plenty of mourners in its wake.

And it kept coming back – the disease’s reign of terror continued through the next generation of Tudors, striking four more times over the coming century.

Henry VII’s son, Henry VIII, was petrified. During one particularly devastating outbreak, he slept in a different bed every night, presumably hoping to outmanoeuvre it. Here was a disease that could strike out of nowhere, often leading to death in a matter of hours; one chronicler wrote that you could be “merry at dinner and dedde [sic] at supper”. Even more uneasily, it seemed to have a peculiar affinity for the nobility. It killed many people at court, and nearly cut short the King’s romance with Anne Boleyn.

Alamy

AlamyTo this day, no one has any clear idea what caused the mysterious English Sweat. But the leading theory is that this mega-outbreak wasn’t caused by the flu, Ebola, or any of the infamous diseases we often hear about.

Instead, the culprit was a type of hantavirus – a rare family of viruses that typically infect rodents.

Not all pandemics are caused by the obvious suspects. Though the media have us whipped up into a frenzy over a select cast of superstar pathogens, the villain in the next global drama may be lurking in the unlikeliest of places; perhaps it hasn’t even been discovered yet.

“I think the chances that the next pandemic will be caused by a novel virus are quite good,” says Kevin Olival, a disease ecologist from the EcoHealth Alliance, a US-based organisation that studies the links between human and environmental health. “If you look at Sars, which was the first pandemic of the 21st Century, that was a previously unknown virus before it jumped into people and spread round the world. So there’s a precedent there – there are many, many viruses out there in the families that we’re concerned with.”

Olival is not alone. Earlier this year, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates warned that the next pandemic could be something we’ve never seen before. He suggested that we prepare for its emergence as we would for a war.

Meanwhile, the WHO is so firmly convinced that they have updated their list of pathogens most likely to cause a massive, deadly outbreak to include “Disease X” – a mystery microorganism which hasn’t yet entered our radar.

Of course, finding the deadly microbes that are still in hiding, or identifying which of the obscure or exotic pathogens that we already know about may pose a threat, is no mean feat. What can be done to hunt them down? And how can we tell which ones could really take off?

Earlier this year, scientists from Johns Hopkins University published a report which aimed to answer these pressing questions. “Our research really arose because everybody in my field was just coming up with things that they thought were going to cause the next pandemic because they were scary, or because they had caused outbreaks – no one was trying to understand what it was about the pathogens that allowed them to have that potential,” says Amesh Adalja, who led the team. “People just kept taking lists [of potential concerns] that other people had made and adding to them, without any real rigour. Why is influenza at the top of the list? Why did we not think about Zika, before 2016? And why did we not think about West Nile in the United States?”

Alamy

AlamyAt the core of the research was the idea that pandemic pathogens are fundamentally weird. Out of millions of viruses on the planet, very few have ever caused a major outbreak. Together with his colleagues, Adalja identified the unusual combination of features that allowed them to do this.

First of all, pandemic pathogens are almost all viruses. This is partly because of their sheer abundance and ubiquity. They are the most numerous biological entities, stalking every ecosystem and invading every type of organism. They can traverse continents and cascade down from the sky in their trillions every day; there are about 800 million viruses on every square metre of the planet.

When you combine their large population sizes with the lightning speed at which they can copy themselves, you end up with a pace of evolution that’s unparalleled in nature. And not only does this mean that they can outsmart our immune systems, but it’s very difficult to develop effective vaccines and anti-viral treatments. While there are several broad-spectrum antibiotics which will kill a wide variety of bacteria, there aren’t yet any equivalent drugs for viruses that actually work.

One group, the RNA viruses – which have genomes made from RNA, rather than DNA – takes these characteristics to the extreme. When these super-pathogens make new copies of their genetic instructions, they don’t include a proofreading step where they check for mistakes, so mutations are common and new variants are constantly being created.

Many of the world’s most notorious pathogens fall into this category, including influenza, HIV, Sars, Mers, Zika, Ebola, polio and rhinovirus (the most prevalent cause of the common cold). But it also includes lesser-known threats, such as Enterovirus 68 – a rare relative of polio with a taste for babies, children and teenagers. It was only discovered in the winter of 1962, when four children were struck down with pneumonia in California.

No one is suggesting that this particular virus is going to suddenly start killing millions of people, but it does satisfy all the criteria – including the final condition that it can infect the respiratory tract. “These viruses are much harder to intervene upon, because breathing is an essential part of life and it’s very hard to stop people from breathing on each other. It’s not the same thing when you’re talking about blood or body fluids,” says Adalja.

Alamy

AlamyAfter laying low in the US population, largely undetected, for several decades, Enterovirus 68 has recently been on the increase. It was linked to an outbreak of a mysterious, polio-like disorder which sprung up in the Midwest of the US in 2014 and killed four people, including a 10-year old girl. Then earlier this month, many more children in the area fell ill, experiencing a sudden paralysis of one or more limbs. So far at least 12 have tested positive for rare enteroviruses such as strain 68.

According to Adalja, enteroviruses are the sort that we should be keeping an eye on. “This group has probably been grossly underestimated in terms of its pathogenicity,” he says. “There’s no enterovirus vaccine, except for polio. And there are probably enteroviruses that we haven’t discovered yet.”

However, perhaps the most enigmatic viruses of all are those which infect other animals. The ‘zoonotic’ pathogens include all the big names, from HIV to Nipah, having caused nearly every pandemic in human history. Just like the recent avian flu outbreak, the 1918 flu pandemic, which killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide, began in birds.

Enter the virus hunters – scientists like Olival who travel the globe, looking for the source of the next pandemic. During the first phase of the US government’s disease surveillance program, from 2009-2014, “we found about a thousand new viruses”, he says. What is the undiscovered pool of viruses? “Oh, we estimate that it could be in the millions. There are probably millions of viruses out there that infect other mammals and could potentially infect people.”

With such an intimidatingly large number of missing viruses in the wild, sifting the ones that will stay in other animals from the ones that could become global killers poses a significant problem. But there are some clues. For example, scientists can look out for genes that might allow a virus to latch onto human cells and sneak inside, or uncover which animals tend to carry it, since most people are much more likely to come into contact with, say, chickens than they are eagles.

“I think it’s one of the most exciting scientific issues right now in the field, moving from the genetic sequence of a virus to saying what is its potential infectivity of humans or other animals and what is the potential pathogenicity,” Olival says. “It’s still a bit of a holy grail, moving from the sequence to some sort of definitive answer – and every group of bugs is going to be different, in terms of which markers and genes to look at.”

Alamy

AlamyBack in 2017, Olival and colleagues from the EcoHealth Alliance decided to investigate where the most dangerous undiscovered pathogens are most likely to be hiding. The team examined thousands of viruses known to infect mammals, including 188 which are also known to infect humans.

One not-so-surprising finding was that the next pandemic will probably emerge from bats. No one knows why, but bats are absolutely riddled with nasty viruses. They’re known to be the source of many, many human pandemics, including Sars, which we picked up from cave-dwelling bats in China, as well as Ebola.

Another predictor that emerged is the range of animals they can infect – and here an obscure group of viruses called the ‘bunyaviruses’ rose to the top of the list. They have a wide variety of potential victims, from insects to plants, which means they’re likely to be able to adapt to infect humans, too. Intriguingly, the family of viruses suspected to have caused the medieval sweating disease, the hantaviruses, belong to the bunyavirus group.

“These are viruses that most people have never heard of, but they rank quite highly in terms of their potential for pathogenicity,” says Olival.

Once a potential pathogen has been discovered, perhaps the greatest challenge is getting the authorities to take it seriously. According to Stephen Morse, an epidemiologist at Columbia University, this is even problematic with notorious viruses like Ebola; exotic new bunyaviruses wouldn’t stand a chance.

“I hate to say that it could have been prevented, but the first report of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa by the WHO said, in the usual bland language, that a rapidly evolving – that should have been a red flag – outbreak of Ebola had occurred, with 43 cases. And that’s a large number,” says Morse. It was months before they mounted a response, by which time it had already made its way into cities.

“I think we are better able to respond to pandemics today than ever, but part of the problem is mobilising the resources and political will to take them seriously,” he says. “I feel the greatest problem is not so much the pathogen – it’s complacency.”

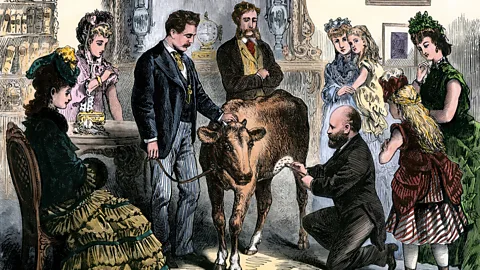

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFinally, no list of obscure pandemic threats would be complete without a mention of smallpox. Though the virus has only been extinct in the wild since 1977, the sheer terror of the disease has largely been forgotten.

Here’s a quick reminder: during its 3,000-year dominion, the smallpox virus killed hundreds of millions of people, including several European kings and queens and nearly the entire population of native North Americans. The mummified head of Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses V bears its characteristic pockmarks, as did the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who required that all photographs of his face were edited to disguise them – he would reportedly have the creators of unflattering images shot.

Smallpox has most of the ingredients you need for a major pandemic: it’s caused by a virus, and though it is unusual in having a genome made from DNA, it belongs to a family that can evolve rapidly and move easily between different animal species. Crucially, the smallpox pathogen is transmitted by breathing in droplets of particles suspended in the air. Though there haven’t been any natural infections since it was eradicated, the virus took its last victim a year after it was declared extinct, when a medical photographer contracted the disease at a lab in Birmingham in 1978. And it could happen again. To this day, smallpox stores exist at labs in Atlanta, Georgia, and in the scientific city of Koltsovo in central Russia.

Back in the 1970s, most people had been vaccinated in childhood. But today state vaccination programs for the virus have been discontinued, and the only people with any immunity are middle aged or older. The United States and many other countries have stockpiles of the vaccine, just in case. Even so, an outbreak of such a contagious disease could easily rip across the globe and kill millions.

Then there’s the risk of bioterrorism. It’s now possible to build viruses from scratch, using nothing more than their genetic sequence for instructions, so you don’t need to be a government scientist to have access to the world’s most lethal pathogen. If it’s ever released, the virus could change the world forever. As Bill Gates put it last year “With nuclear weapons, you’d think you would probably stop after killing 100 million. Smallpox won’t stop. Because the population is naïve, and there are no real preparations. That, if it got out and spread, would be a larger number.”

It may have been centuries since the dreaded sweating sickness of 1485, but we can still learn from the past. The flu is seen as a likely candidate for the next pandemic – not the only candidate. And if the scientists have got it right, failing to take D-list viruses seriously could be a catastrophic mistake.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.