Why the flu of 1918 was so deadly

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Spanish flu killed quickly, and it killed in huge numbers. Other flu pandemics in modern times have been far less deadly. Why?

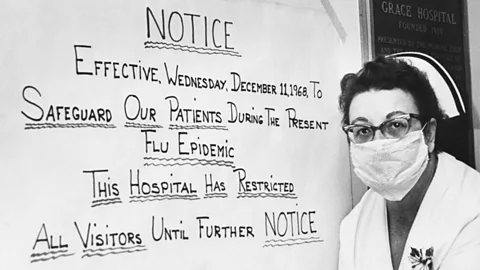

If you are reading this article, you have probably lived through at least one global flu pandemic – one just as contagious as the deadly 1918 strain. There was the 1957 outbreak (the so-called ‘Asian flu’) and the ‘Hong Kong flu’ in 1968. Forty years later, in 2009, there was ‘swine flu’.

Each pandemic had similar origins, emerging, one way or another, from an animal virus that evolved to be to able pass between humans. Yet the death tolls were barely comparable. Between 40 and 50 million are thought to have died from the 1918 strain – compared to two million for the Asian and Hong Kong influenzas, and 600,000 for the 2009 swine flu, both of which had a mortality rate of less than 1%.

The human cost of the 1918 pandemic was so great that many doctors continue to describe it as the “greatest medical holocaust in history”. But what made it so deadly? And could that knowledge help us prepare for a similar pandemic today?

You might also like:

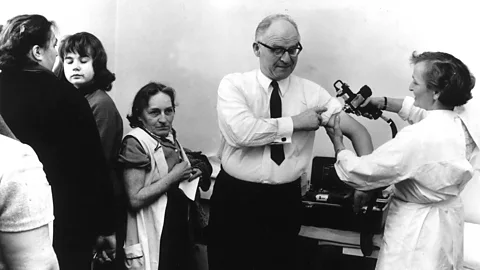

An understanding of these pandemics would be impossible without a recognition of the huge leaps in medicine over the 20th Century. Doctors in 1918 had only just discovered the existence of viruses. “And they certainly didn’t know that this was a virus causing these diseases,” says Wendy Barclay at Imperial College London. They were a long way from the anti-viral medications and vaccines that can now help to stem the spread and promote a quicker recovery.

Many flu deaths are also caused by secondary, bacterial infections that take root in the weakened body, leading to pneumonia. Antibiotics like penicillin – discovered in 1928 – now allow doctors to reduce that risk, but in 1918 there was no such treatment. Nor did they have vaccines, which now help to protect those who are most at risk. “Our health care infrastructure and diagnostic and therapeutic tools are so much more advanced,” says Jessica Belser, who works at the influenza division of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Besides the lack of basic medical tools in 1918, deaths would have also been a direct result of the appalling living conditions at this tragic time in human history. The trenches would have been the perfect breeding grounds for infections among the World War One soldiers. “The virus emerged when populations, which previously had little contact with each other, were brought together on the battlefield,” says Patrick Saunders-Hastings at Carleton University in Ottawa. “And on a lot of cases they were dealing with other injuries and they were under-nourished.” Vitamin B deficiencies, in particular, have been noted to increase mortality rates in later pandemics, he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven those left at home were still living in closed, crowded conditions that led to greater exposure to the virus. This not only accelerated transmission, increasing the chances that people would become infected; it also increased the severity of the symptoms. “We know that the bigger the dose that gets into you, the sicker you get, because the virus is able to overwhelm the immune system and take a hold more potently in your body,” says Barclay.

“It’s well understood that improved sanitation and hygiene, associated with industrialisation and general reductions in poverty, have contributed significantly to overall reductions in infectious disease mortality in the 20th Century,” agrees Kyra Grantz at the University of Florida. Analysing records from Chicago during the 1918 pandemic, she has shown that factors such as population density and unemployment directly influenced someone’s chance of catching the disease.

Interestingly, the data from Chicago also appeared to show a strong link between mortality risk and rates of illiteracy within different regions of the city. This may be because illiteracy was simply a proxy for other factors associated with poverty. But it’s possible that a person’s lack of education also played a direct role in the disease’s progression.

“There were tremendous efforts made by public health officials to halt the outbreak in Chicago, including a city-wide quarantine, school closures, and bans on certain social gatherings,” Grantz says. “Those measures will only be effective if people are aware of and adhere to them.”

Such factors notwithstanding, many scientists believe that the virus itself was also particularly virulent – although it has taken more than a century to understand exactly why.

By the time the techniques to capture, store, cultivate and analyse viruses had been invented, the original deadly strain had long since disappeared. But recent advances in genomic technology have now allowed scientists to resurrect an active virus from blueprints from inert historic samples, which they have then used to infect laboratory animals such as monkeys to study its effects.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBesides replicating very quickly, the 1918 strain seems to trigger a particularly intense response from the immune system, including a ‘cytokine storm’ – the rapid release of immune cells and inflammatory molecules. Although a robust immune response should help us fight infection, an over-reaction of this kind can overload the body, leading to severe inflammation and a build-up of fluid in the lungs that could increase the chance of secondary infections. The cytokine storm might help to explain why young, healthy adults – who normally find it easier to shake off flu – were the worst affected, since in this case their stronger immune systems created an even more severe cytokine storm.

To understand why the 1918 strain would have had this effect, we need to return to its origins.

The 1918 flu is thought to have only just evolved from a strain that typically infected birds – acquiring mutations that allowed it to infect the upper respiratory system. This meant that it could be transmitted through the air – in coughs and sneezes – more easily.

This is important for two reasons. Without previous exposure to the virus, the body’s immune system would not have been able to produce an efficient response.

Just as importantly, however, the virus itself had not yet fully adapted to life in a human body. Contrary to expectations, it is not normally within a flu virus’s interests to kill the host. “It’s not good for the virus to kill the host as soon as it infects it, because that host has less chance of passing the virus on to other people,” says Barclay. Instead, it just needs to hitch a ride for long enough to spread through your coughs and sneezes. As a result, most viruses evolve to become less pathogenic overtime – but the 1918 virus had not yet made those adjustments.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe later pandemics, in contrast, had already incorporated some of these adaptations before they spread across the world – and were less deadly as a result.

The 1957 pandemic, for instance, emerged when an existing human strain of the virus acquired some genes from an avian variety. The result was highly contagious strain, but the existing human components meant it was still less deadly than a virus of purely of avian origins. Similarly, the 1968, the so-called Hong Kong flu came from another “reassorted” version of existing viruses that already carried the less virulent adaptations.

The 2009 pandemic, meanwhile, was a swine flu that had originated in pigs – which, although not identical to humans, are at least closer to us than birds, meaning that it had already accrued some adaptations that toned down its virulence.

Studying these processes not only help us understand tragedies of the past; by identifying the genetic features that were responsible for the devastating effects of the 1918 pandemic, we may be better prepared to prevent similar tragedies in the future.

“From my perspective, having more information about past pandemic viruses can help guide our decision making and knowledge and guide how we will best address future pandemic threats,” says Belser.

--

David Robson is a senior journalist at BBC Future. He is @d_a_robson on Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.