The flu that transformed the 20th Century

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Spanish flu emerged as the world was recovering from years of global war. It was to have some surprising and far-reaching effects.

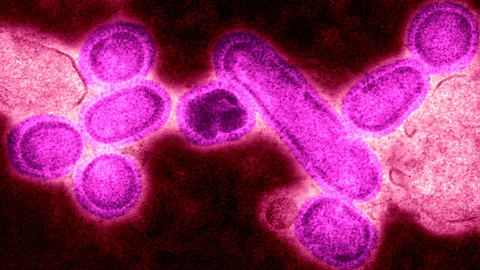

The picture we have of the 1918 flu pandemic is vastly more detailed today than it was 20 years ago, let alone 50 or 100 years ago. But it’s nowhere near complete. Pathologist Jeffery Taubenberger of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases – the man who in 2005, with his colleague Ann Reid, published the genetic sequence of the virus responsible for the pandemic – said at a recent conference there were still many unanswered outstanding questions.

Researchers all over the world are working hard to answer them. But what they have already uncovered might surprise you.

The fittest were among the most vulnerable

Austrian artist Egon Schiele died of influenza in October 1918, just a few days after his wife Edith, who was pregnant with their first child. In the interim, though desperately sick and grieving, he worked on a painting that depicted a family – his own – that would never exist.

Schiele was 28 years old, firmly within an age group that proved acutely vulnerable to the 1918 flu. It is one reason why his unfinished painting, The Family, is often described as a poignant testimony to the disease's cruelty.

You might also like:

Because it was so deadly to 20-to-40-year-olds, the disease robbed families of their breadwinners and communities of their pillars, leaving large numbers of elderly people and orphans with no means of support. Men were at greater risk of dying than women, in general, unless the women were pregnant – in which case they died or suffered miscarriages in droves.

Scientists don't know precisely why those in the prime of life were so vulnerable, but a possible clue lies in the fact that the elderly – always a high-risk group for flu – were actually less likely to die in the 1918 pandemic than they had been in flu seasons throughout the previous decade.

One theory that potentially explains both observations is "original antigenic sin" – the idea that a person's immune system mounts its most effective response to the first strain of flu it encounters. Flu is a highly labile virus, meaning that it changes its structure all the time – including that of the two main antigens on its surface, known by the shorthand H and N, that engage with the host's immune system.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere's some evidence to suggest the first flu subtype that young adults in 1918 had been exposed to was H3N8, meaning they were primed to fight a very different germ from the one that caused the 1918 flu – which belonged to the H1N1 subtype. Following the same logic, the elderly may have been relatively protected in 1918 by dint of having been exposed to an H1 or N1 antigen that was circulating in the human population circa 1830.

Death rates varied greatly across the globe

Flu has sometimes been called a democratic disease, but in 1918 it was anything but. If you lived in certain parts of Asia, for example, you were 30 times more likely to die than if you lived in certain parts of Europe.

Asia and Africa suffered the highest death rates, in general, and Europe, North America and Australia the lowest, but there was great variation within continents too. Denmark lost around 0.4 per cent of its population, while Hungary lost around three times that. Cities tended to suffer worse than rural areas, but there was variation within cities too.

People had a vague sense of these inequalities at the time, but it took decades for statisticians to put hard numbers on them. Once they had, they realised that the explanation must lie in differences between human populations – notably, socioeconomic differences.

In the US state of Connecticut, for example, the newest immigrant group – the Italians – suffered the worst losses, while in Rio de Janeiro, then the capital of Brazil, it was those inhabiting the sprawling shanty towns at the city's edge who were hit hardest.

Paris presented a conundrum – the highest mortality being recorded in some of the wealthiest neighbourhoods – until the statisticians realised who was dying there. It wasn't the owners of the grand apartments, but their overworked maids who slept in chilly chambres de bonne high up under the eaves.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAll over the world, the poor, immigrants and ethnic minorities were more susceptible – not, as eugenicists liked to claim, because they were constitutionally inferior, but because they were more likely to eat badly, to live in crowded conditions, to be suffering from other, underlying diseases, and to have poor access to healthcare.

Things haven't changed all that much. A study of the 2009 flu pandemic in England showed that the death rate in the poorest fifth of the population was triple that in the richest.

It wasn't just a respiratory disease

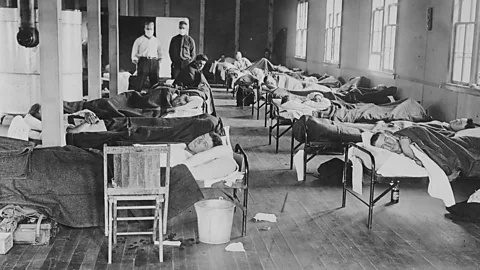

The vast majority of those who fell sick recovered, but among the unlucky minority who did not – and they were at least 25 times more numerous, proportionately, than in other flu pandemics – the disease took a grisly course.

They began to have trouble breathing, and their faces turned a mahogany colour. The mahogany darkened to blue – an effect doctors dubbed "heliotrope cyanosis" – and by the time they died they were black all over. The cause of death in almost all cases was not the flu itself, but opportunistic bacteria that colonised the lung lesions created by the virus, producing the symptoms of the "old man's friend", pneumonia.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat much is relatively well known. Less well-known is that the flu affected the entire constitution. Teeth and hair fell out. People reported dizziness, insomnia, loss of hearing or smell and blurred vision. There were psychiatric after-effects, notably "melancholia" or what we might now call post-viral depression.

It continues to be true that the waves of death associated with both flu pandemics and annual flu seasons are followed by waves of death due to other causes, notably heart attacks and strokes – indirect consequences of the inflammatory response to flu. Flu wasn't in 1918, and still isn't, exclusively a respiratory disease.

The pandemic transformed public health…

Eugenics was a mainstream current of thought both before and after the 1918 flu, but the pandemic undermined it in at least one domain: infectious diseases.

Previously, social Darwinist – and misguided – thinking about some human "races" or castes being superior to others had mixed insidiously with the insight of Louis Pasteur and others that infectious diseases were preventable. They produced a toxic cocktail of an idea: people who caught infectious diseases only had themselves to blame.

The pandemic revealed the truth: that although the poor and immigrants died in higher numbers, nobody was immune. When it came to contagion, in other words, there was no point in treating individuals in isolation or lecturing them on personal responsibility. Infectious diseases were a problem that had to be tackled at the population level.

Starting in the 1920s, this cognitive shift began to be reflected in changes to public health strategy. Many countries created or re-organised their health ministries, set up better systems of disease surveillance, and embraced the concept of socialised medicine – healthcare for all, free at the point of delivery.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere had been moves in this direction earlier – you don't put a universal healthcare system in place at the drop of a hat – but the pandemic seems to have galvanised governments. In Britain these efforts came to fruition in 1948, with the birth of the National Health Service, but Russia already had a centralised, fully public healthcare system up-and-running by 1920. To begin with only urban folk benefited (rural populations were finally covered in 1969), but it was still a major achievement, and the driving force behind it was Vladimir Lenin.

…and transformed society in other ways too

The expression "the lost generation" has been applied to various groups of people who were alive in the early 20th Century, including the talented American artists who came of age during the First World War, and the British army officers whose lives were cut short by that war.

But it could reasonably be argued, as I do in my book Pale Rider, that the title should really go to the millions of people in the prime of life who died of the 1918 flu, or to the children who were orphaned by it, or to those, not yet born, who suffered its slings and arrows in their mothers' wombs.

The nature of the 1918 pandemic, and of scientific knowledge at the time, means that we don't know exactly how many there were in those three groups, but we can be certain that each one outnumbered both the Jazz-Age artists and the 35,000-odd British officers who died in combat (South Africa had an estimated 500,000 "flu orphans" alone).

Those who survived the flu in utero to be born, lived with the scars until they died. Research suggests that they were less likely to graduate or earn a reasonable wage, and more likely to go to prison, than contemporaries who hadn’t been infected.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is even evidence that the 1918 flu contributed to the baby boom of the 1920s, by leaving behind a smaller but healthier population that was able to reproduce at higher rates.

That the 1918 flu cast a long shadow over the 20th Century is not in doubt. We should bear that in mind as we prepare for the next one.

Laura Spinney is the author of Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World, published by Penguin Books.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.